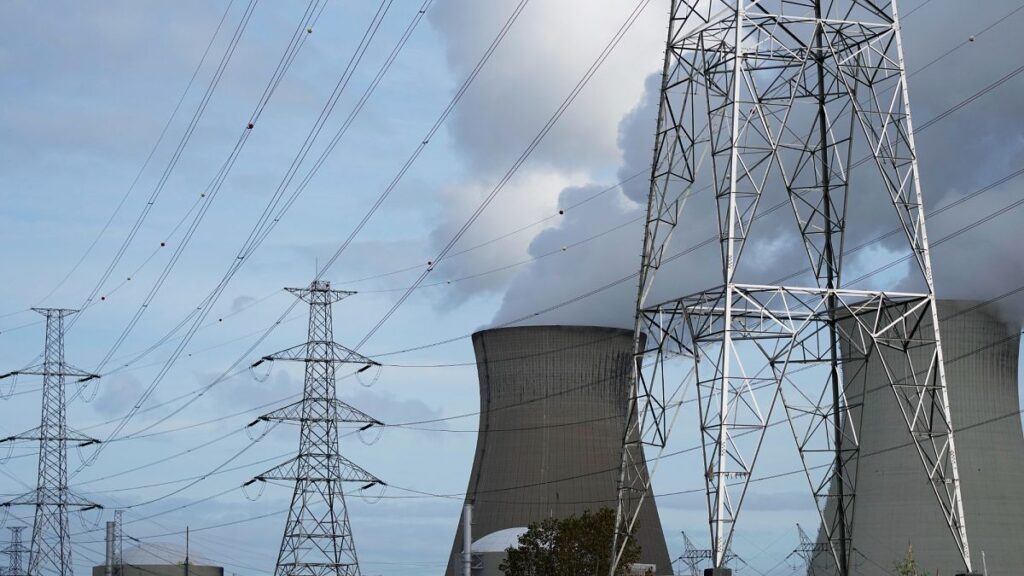

Several countries across Europe are pivoting or have made U-turns over the use of nuclear power, as governments seek greater energy security.

Belgium was in the spotlight earlier this month when its parliament voted to repeal a 2003 law that stipulated the gradual phaseout of nuclear energy.

The motion it adopted on 15 May allows for the possibility of reviving the country’s atomic industry in the future, including building new power stations.

Belgium’s original plan to phase out its seven nuclear reactors by 2025 was pushed back by a decade in 2022 due to energy uncertainty caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The current conservative-led coalition government, led by Prime Minister Bart De Wever, came into power in February, and decided that the shift was necessary to meet its energy challenges.

“We know that it’s a low-carbon energy source, which means we can meet our European climate targets, but it’s also an abundant energy source,” said Belgium’s Energy Minister Mathieu Bihet.

“We have three objectives that are shared by our European partners. They are security of supply, a controlled price and low-carbon energy. And nuclear power meets all three criteria,” he added.

Belgium is far from alone — other EU member states such as Germany, Denmark, and Italy are reconsidering their stances on nuclear power.

“I think it’s obviously due to the current situation, with enormous geopolitical uncertainty and dependence on gas, which is still very strong,” said Adel El Gammal, professor of energy geopolitics at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB).

“So, quite naturally, anything we can do to make ourselves more independent of gas, we have to do. Nuclear power is one way,” El Gammal, who is also secretary general of the European Energy Research Alliance (EERA), told Euronews in an interview.

The EU has around 100 nuclear reactors in 12 countries (Belgium, Bulgaria, Spain, Finland, France, Hungary, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden). Almost a quarter of the electricity produced in the EU comes from nuclear power, according to the latest data from Eurostat.

Nuclear plants release few pollutants into the air, which have made them an option as nations around the world seek clean energy to meet climate change targets. However, their construction and demolition produce large amounts of greenhouse gases.

Opponents have for decades cited the challenges involved with processing long-lived radioactive waste to lobby against new plants. Climate activists also say that relying on nuclear power risks slowing the rollout of renewable energy sources.

EU nations reconsider their position

Germany in 2011 committed to phasing out nuclear power, thereby reinforcing its status as the leading voice of the anti-nuclear movement within the EU. This was achieved in April 2023 with the closure of the country’s last three power stations.

During the German election campaign at the start of this year, then-candidate and now Chancellor Friedrich Merz, had promised to look into reviving the sector.

While Merz said in January that reopening the country’s nuclear plants would “most likely not be feasible”, his campaign vow marked a significant ideological shift in the German political landscape.

Just last week, Merz’s government indicated it would stop blocking efforts to treat nuclear power on par with renewables in EU legislation, the Financial Times reported.

Italy is also considering reintroducing nuclear power.** At the end of the 1980s, Rome decided to put an end to nuclear power.

But Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s government has set 2030 as the target date for returning to nuclear power, according to the country’s energy security minister. The coalition government argues that this resource will help to ensure the country’s energy security and achieve the environmental objectives of decarbonisation.

For similar reasons, coal-dependent Poland has embarked on a vast nuclear programme. Warsaw decided in 2022 to build its first power station, with the first reactor scheduled to be operational from 2033.

Earlier this month, EU renewables darling Denmark said it was considering lifting a 40-year-old ban on nuclear energy, and that it would analyse the potential benefits of a new generation of nuclear power technologies.

And just last week, Sweden passed a law to fund a new generation of nuclear reactors.

Meanwhile, in Spain, the government is under pressure to reconsider phasing out nuclear power following the giant blackout that hit the country at the end of April.

A long-term choice

El Gammal of the EERA suggested two strategies for a return to nuclear power, which are not exclusive but very different in their development.

“The first is to extend existing facilities as far as possible. And here, I would say that if it can be done under well-established safety conditions, it should be done as far as possible. It’s a no-brainer,” he explained.

“On the other hand, relaunching a new nuclear industry or relaunching the construction of new reactors is much more complicated, because first of all, the budgets involved are extremely large,” El Gammal added. “Then there’s the time it takes to build a power station. It takes around ten years.”

“Given the urgent need for strategic autonomy and climate change, this is a major problem”, he said. All the more so as “renewable energies are coming on stream much more quickly”.

Building an atomic energy industry means taking a long-term view, and anticipating the cost of different energy resources over an extended period of time.

However, as El Gammal pointed out, renewable energies are based on a logic of decreasing costs and increasing technology, “whereas in mature technologies, such as nuclear power, the costs are highly dependent on raw materials, i.e. cement, steel, in other words, raw materials whose cost is tending to increase.”

But nuclear and renewables are not contradictory strategies; they can go hand-in-hand, he stressed.

To try and bring certainty to the industry, Belgium’s energy minister Bihet suggested setting up joint projects and multi-state investments, which he said “will bring down costs and also stabilise investment to give companies confidence”.

Read the full article here