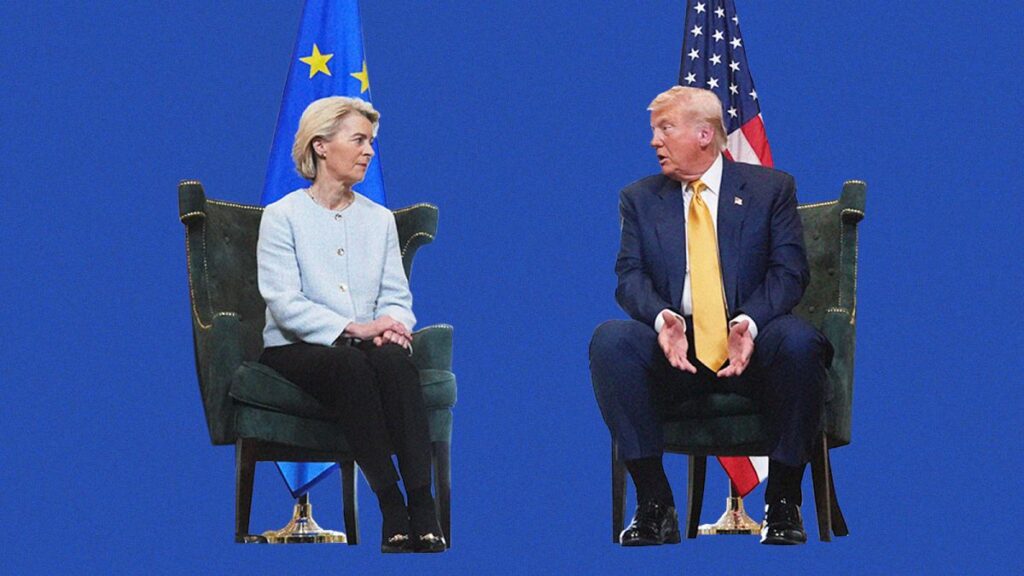

This past weekend, Ursula von der Leyen did something she rarely does: she wrote an op-ed defending one of her signature policies.

“Solid if imperfect” was how the president of the European Commission chose to describe the trade deal that she personally struck with Donald Trump in late July. It was a partial admission of defeat, acknowledging the discontent caused by the painful 15% tariff imposed on the vast majority of EU products bound for America.

The remainder of the column, published in several European newspapers, was devoted to highlighting the agreement’s greatest – and perhaps sole – benefit: putting an end to the energy-sapping, headline-hogging clash between the two sides of the Atlantic. For all its flaws and pitfalls, it represents a full stop.

“The agreement is a deliberate choice, the choice of stability and predictability over that of escalation and confrontation,” she said.

“An EU tariff retaliation would risk triggering a costly trade war with negative consequences for European workers, consumers and industries,” she went on.

“In any escalation, one fact however would not change: the US would maintain its unpredictable and higher tariffs regime.”

Less than 24 hours after the op-ed’s publication, with timing so sharp it seemed deliberate, Trump took to social media to dismantle von der Leyen’s core point of “stability and predictability” by threatening a fresh raft of punishing tariffs.

“I put all Countries with Digital Taxes, Legislation, Rules, or Regulations on notice that unless these discriminatory actions are removed, I, as President of the United States, will impose substantial additional Tariffs on that Country’s Exports to the U.S.A., and institute Export restrictions on our Highly Protected Technology and Chips,” he wrote.

“America, and American Technology Companies, are neither the ‘piggy bank’ nor the ‘doormat’ of the World any longer. Show respect to America and our amazing Tech Companies or, consider the consequences!”

The “notice” did not name-check the EU or any nation or organisation. But given the bloc’s world-leading position in reining in Big Tech, the subtext was unmissable.

It was the kind of threat that officials in Brussels have contended with since Trump’s return to the White House: far-reaching, whimsical and deeply ominous. But unlike previous threats, which were seen as rhetorical tactics to pile pressure on negotiators, the new warning was particularly alarming because it came after the conclusion of the trade deal, which both sides formally endorsed in a joint statement.

Throughout the negotiations, US officials had repeatedly denounced the bloc’s tech regulations, such as the Digital Services Act (DSA), which is meant to combat illegal content and disinformation online; the Digital Markets Act (DMA), which aims to guarantee free and fair competition; and the Artificial Intelligence Act, which lays out rules for AI systems deemed risky for human safety and fundamental rights.

Washington wanted these laws to be on the table and up for grabs. Brussels flatly refused, insisting its right to regulate was a sovereign matter.

In the end, the joint EU-US statement included one brief commitment to address “unjustified digital trade barriers”, but only in the context of network usage fees and electronic transmissions. The critical pieces of legislation survived, seemingly intact.

Sovereignty up for grabs

It was a victory the Commission was quick to hail.

“In concluding the agreement, the EU stood firm on its fundamental principles and stuck to the rules it had set for itself,” von der Leyen wrote in her op-ed.

“It is up to us to decide how best to guarantee food safety, protect European citizens online and safeguard health and safety. The agreement safeguards the values of the Union while promoting its interests.”

Trump’s latest threat, however, suggests the win might be illusory.

His profound aversion to digital regulation, which he and his deputies portray as geared specifically against US firms and therefore US interests, remains alive and well, regardless of any trade deal, joint statement and handshake before the TV cameras.

The phrasing of his message makes it clear he is willing to exert America’s economic hard power – in this case, tariffs and microchips – to extract legislative concessions from foreign jurisdictions that would effectively amount to subjugation.

The heavy-handed strategy echoes China’s decision in spring to restrict the flow of rare earths, which von der Leyen compared to “blackmail”. Despite the severe implications, the EU refrained from retaliating against China and opted for dialogue, the same strategy it followed after Trump’s contentious announcement of “reciprocal” tariffs.

“Hopes of a softer Trump line on digital trade after the framework agreement have been dashed. Appeasement has barely lasted a week,” said Tobias Gehrke, a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR).

“Washington and Beijing are taking economic hostages left and right. Europe has long hoped it could stay out of that game. The EU has cards to play, but it has yet to dare to play them as leverage.”

Adding to the anxiety in Brussels is a report from Reuters indicating the Trump administration is considering slapping sanctions on EU officials who work on the DSA, a law that Republicans have lambasted as a tool for stifling free speech.

Marco Rubio, the US Secretary of State, has instructed his diplomatic corps to actively lobby against digital regulations that target American firms.

“We are monitoring increasing censorship in Europe with great concern, but have no further information to provide at this time,” a spokesperson for the State Department told Euronews when asked about potential sanctions.

The Commission has forcefully rejected the characterisation as “completely wrong and completely unfounded”, arguing that the DSA and the DMA respect freedom of information and treat all firms equally, “irrespective of their place of establishment”.

But that assertion is unlikely to convince the White House, which is closely attuned to Big Tech’s political agenda. Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg, Apple’s Tim Cook, Google’s Sundar Pichai and X’s Elon Musk, whose companies are all under the Commission’s scrutiny, took prime seats at Trump’s inauguration in January.

The growing ideological alignment between Republicans in Washington and CEOs in Silicon Valley bodes ill for the European fight to preserve regulatory sovereignty. After all, the joint EU-US statement is fundamentally non-binding and leaves the door open for Trump to freely re-interpret, or outright ignore, the agreed-upon terms.

The trade war, it seems, is not over. It is just evolving.

“We stand ready for dialogue with the United States – but we will never negotiate Europe’s legislation under threats,” Valérie Hayer, a French member of the European Parliament who leads the liberal group part of von der Leyen’s centrist coalition.

“We make law through our own European democratic process, not by foreign pressure. Allies don’t bully allies.”

Read the full article here