When my two sisters and I travelled to our late mother Mira’s home village of Spisska Stara Ves in Slovakia last August, it was exactly as we had imagined: a pastoral town, set against the backdrop of the Tatras mountains, just as she had described. One main road anchored by the gothic 14th-century church, dotted with modest homes, a few restaurants, a couple of grocery stores, all diminutive against the dramatic green landscape.

My sister Jeannette had a moment of recognition, as if this place itself was embedded in her DNA. “No wonder I love living in the country,” she said, making the connection between this tiny outpost and her semi-rural home in Melbourne, at an address Mira simply called “whoop-whoop”.

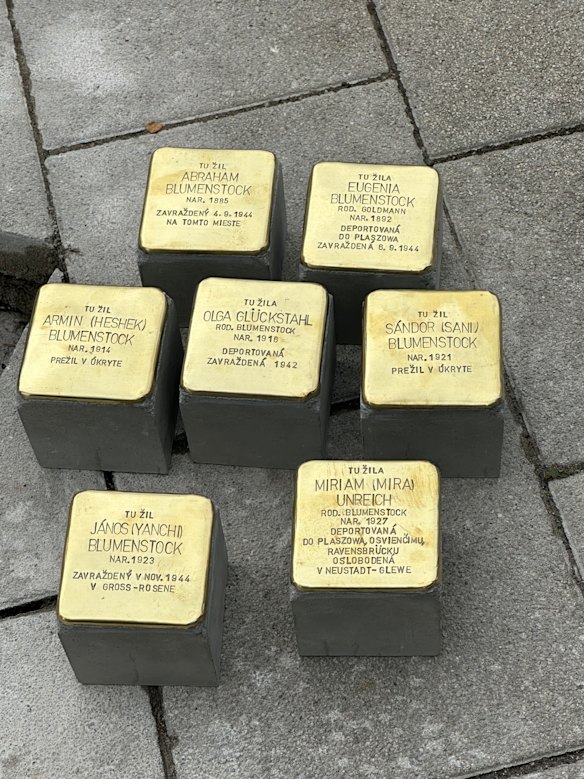

But we were not there on a picturesque summer holiday. Instead, we had come together with our cousins from three corners of the world to lay down memorial stones in honour of our grandparents and their children, our parents. In that family of seven, five were captured by the Nazis. Of those five, only my mother Mira Blumenstock returned.

Although so much of Spisska Stara Ves is unchanged since that time, the Blumenstock family home is no longer standing. In its place is the Kulturny Dom – the municipal cultural centre – with its own library and impressive auditorium. To look at it, flanked by bright flowerbeds and a grassy town square, you would never know what happened there. This is why we were laying the stones.

In that exact spot, on September 3, 1944, loud knocking rattled Mira’s front door late at night. “Partisans!” a voice shouted. But that wasn’t who had come. Nazis had been given a tip-off that eight Jewish families remained in this little enclave, out of an original 300-strong Jewish community before the war. Among those already deported was my aunt Olga, a 26-year-old newlywed, never to be seen again.

On this night, when the Nazis ambushed their home, my grandfather Dolfie jumped through a window – only to be fatally shot when he landed. My grandmother Genya and her two youngest children – Mira, 17, and her 21-year-old brother Yanchi – were carted off to Plaszow concentration camp. Genya would be executed within hours of arriving; Yanchi was killed in the next camp he was transferred to. Mira, still a teenager, survived four camps – including Auschwitz – and a death march.

It was my sister Lilianne who had come up with the idea of laying “Stolpersteine” into the pavement at this location, outside our grandparents’ home. They are small brass memorial blocks – in the case of the Blumenstock family, seven in all – separately engraved with each person’s name and details of their fate.

There are now 116,000 such stones all over Europe, the brainchild of artist Gunter Demnig, in what is the largest decentralised memorial project in the world. They are called “Stolpersteine”, or “stumbling stones”, because Demnig wanted people to stop in their tracks: not only with their feet, but with their hearts.

Another reason – perhaps apocryphal when it comes to Demnig’s choice – is often cited. In Nazi Germany, when someone tripped on a cobblestone the antisemitic joke was uttered: “A Jew must be buried here.” Demnig also found inspiration from the Jewish text known as the Talmud, where it is written: “A person is only forgotten when his or her name is forgotten.”

The mayor of Spisska Stara Ves held a dignified ceremony for the laying of the stones, and it was touching for us to see how many townspeople turned up, dressed in their finery. A quartet of musicians played Jewish songs including tunes from Fiddler on the Roof.

In the speech he delivered, Mayor Jan Kurnava said that the stones “give a voice to those whose voices were taken away [and] it is our duty to remember … not only the tragedy, but also that these people were our neighbours, our friends, our classmates, our fellow citizens. Their names belong to the history of our town, and their stories are part of our shared memory.”

Among those who attended was a man of 90, who arrived on his bicycle. He was just nine when my grandfather was shot dead, and remembered the day that the townspeople collected Dolfie’s body and buried him, crafting together a funeral at the Jewish cemetery. I was shocked to learn it was an open casket, which is not something done under Jewish burial law. But of course by that time there were no Jews left to supervise.

Upon our arrival in the town, our first stop was Dolfie’s gravestone, which Mira and her two surviving brothers had restored. It is striking and dignified, and sits in painful contrast to the disorder of the many fallen tombstones there, the writing on them muddied and weathered.

So many people cautioned me about this trip in which I traced my mother’s steps: not just to Spisska Stara Ves, but to the High Tatras, where she loved to holiday, and to Poland, where Dolfie had originally been born. They said that I would be constantly aware of the blood beneath the streets, given that more than 90 per cent of Polish Jews – some 3 million – were killed during the Holocaust, but that proved not to be the case. In Krakow, I could appreciate the winding streets, the grassy pockets of park, the old buildings, some of which – with their tiers, icing-like scrollwork and pastel colours – made me think of wedding cakes.

In Poland, I visited two concentration camps, both of which Mira had suffered through. I had thought Plaszow was only an open site, with nothing left of the camp, but that wasn’t entirely true. The grounds also form part of the Plaszow museum, and walking around them you get a sense of the camp’s scale and size, with a number of small markers or remnants, with signs explaining them further.

My tour guide works at the museum and helped me research Mira’s story: he showed me where she would have stood when she first arrived, and where she had been separated from her mother in the “selection”, when prisoners were put into two groups – those to live, and those to die.

What I did not expect was to climb a hill and to reach a cavity at the top. Covered in grass and flanked by a towering statue, it was clearly sacred ground.

It took me a while to realise that this was also the site of Genya’s death: the pit she was made to walk over, crossing on a wooden plank, shot when she was suspended above it. Given that the Nazis burnt the bodies to hide evidence of their crimes, her ashes must still be there, buried deep in the earth.

Some might find this horrific, but not me: I was raised with the Holocaust on both sides of my family tree, and all four of my grandparents were murdered. I never expected to visit Genya’s final resting place, or to have a place where I could pay my respects and pray.

I said a different kind of prayer when I visited Auschwitz. Nothing prepares you for the scale of it, or its industry. Although now it is packed with tourists, nothing can sanitise the horror. One can see the brutal conditions under which the prisoners lived, especially in Block 11, the camp prison. There, four people were forced into tiny “standing cells”, unable to sit down, where the air is stiff – the entire area has only a five-by-five centimetre covered opening – and in which they often died of starvation or suffocation.

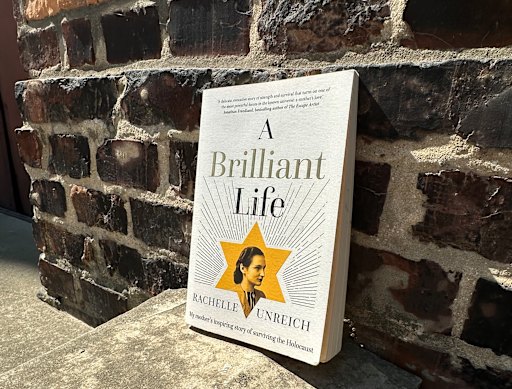

It was impossible to imagine my vibrant mother Mira, still a teenager, famously dimpled and beautiful, wandering around this camp. It is an inhuman place. While on the tour, I had been carrying a copy of the book I wrote about Mira, A Brilliant Life, which features a photo of her on the cover, atop a yellow Jewish Judenstern transposed to look like a shining star.

On a whim, I took the book out of my bag and propped it up against one of the barracks. The sun caught its gold embossing, sending light in different directions. Seeing it there was almost more satisfying than writing the book itself. It felt like such an act of furious defiance – and exalted triumph.

The Nazis were gone, with only a legacy of hate and ugliness to remember them by. Mira had survived, and her story – which she recounted in such precise detail – would exist forever. Not just what she had endured, but how she lived, with such vitality and joy and shining goodness. Her light was more powerful than their darkness.

This, I now realise, is at the core of Holocaust remembrance. “Never forget” has become its catchphrase, to ensure that the evil is never obliterated or diminished, that the lessons about letting hate run unchecked are never ignored.

But there is an accompanying sentiment that is true as well. I want to always remember: my mother’s Jewish pride, her strength, her magic. Not just the horror she experienced, but the unbelievable beauty she encapsulated as well.

When her life ended, her force did not. And that is what will always endure.

International Holocaust Remembrance Day is on January 27.

Read the full article here