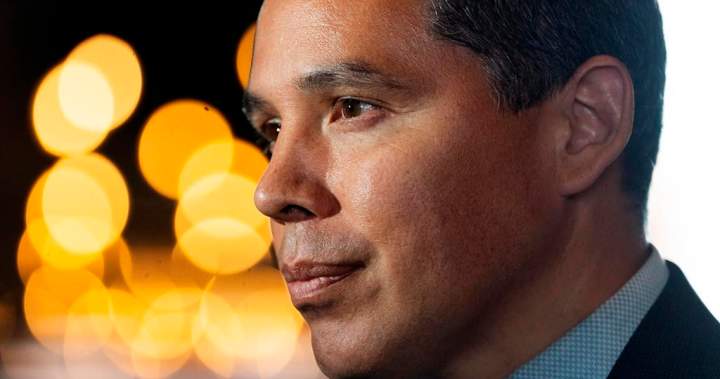

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami President Natan Obed warns that Donald Trump’s recent rhetoric about his country’s need to control Greenland will soon be directed at Canada’s North.

And Obed said that at a moment when geopolitical attention is trained on the Arctic, Indigenous leadership must be included in broader discussions of Canadian sovereignty and security.

Speaking at an Arctic security symposium at the University of Ottawa Wednesday, Obed suggested that Trump’s arguments — for instance, that Denmark and Greenland can’t defend the Arctic nation from Russian or Chinese incursion — could be deployed to push for greater American control of Canada’s northern territories.

“The argument often starts with the colonial power (not having) done enough to improve the land, basically to improve the state of conditions within the space. And so therefore they don’t actually have territorial authority over it,” Obed said.

“No other nation states can come to us and tell us what we should have done, or what we have to do to maintain sovereignty over our homeland. We do that ourselves, and we’ve articulated that again and again over the past 200 years.”

Obed’s comments were on one level directed at Trump’s obsessive desire, only recently abandoned, that America be given “ownership” over Greenland.

The U.S. president backed down from his increasingly militaristic language around Greenland’s annexation after a meeting with NATO chief Mark Rutte last week, but not before the episode shook the transatlantic defence alliance and European capitals.

But Obed’s speech was also directed at Prime Minister Mark Carney and the federal government and its relationship to First Nations, Métis and Inuit leadership. Obed noted with approval Carney’s recent speech in Davos, Switzerland, where the prime minister urged “middle powers” to work together in the face of the world’s superpowers — most immediately the United States.

Get daily National news

Get the day’s top news, political, economic, and current affairs headlines, delivered to your inbox once a day.

Carney’s speech, which was widely praised by both international and domestic commentators, depicted a world where the “rules-based international order” has been exposed as a fiction and where powerful nations seek to impose their will on smaller ones.

“I couldn’t help but think of some of the terms that were used and the application of those terms in our context. Large main powers only applying the rules when it is convenient, and excusing themselves when it is not,” Obed said.

“And I thought about the juxtaposition with Indigenous people’s rights in this country and the large main power of governments excusing themselves when convenient, when they do not want to implement our existing rights or not implement legislation that would benefit our lives and create equity.”

The Carney government — as well as Canada’s national security and defence communities — have put a greater emphasis recently on the need for Ottawa to project sovereignty over Canada’s vast northern region, and to secure the territory from threats.

Anita Anand, Canada’s foreign affairs minister who previously served in the defence portfolio under the previous Liberal government, told the symposium that “defending Canada’s Arctic sovereignty is an unquestionable national security priority of this government.”

“And it is not a secondary concern. It is not a regional issue, but central to how we protect Canada in our front yard and how we contribute to global security,” Anand said Wednesday.

“I see the pace at which threats are evolving, I see the growing military interest in the Arctic, and I see how critical Canada’s North is to the defence of North America.”

Anand added that the Canadian government must “partner” with Inuit and First Nations in the north to achieve those security goals.

“The basic truth is this: you cannot defend what you cannot see or what you’re not prepared to defend,” she said.

Adam Lajeunesse, an associate professor at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, told Global News that it’s not necessarily a military threat from a hostile foreign power that Canada needs to worry about in the North.

Instead, it’s “hybrid” threats — things like illegal fishing, increased scientific research and mapping incursions, espionage threats like misinformation or sabotage, data collection — that are a growing concern around the world, Lajeunesse said.

As ever, the current administration in Washington also presents an unpredictable element in the discussion.

“At a political level, what we’re seeing after Greenland is a renewed concern for challenges that may emerge from Washington,” Lajeunesse said.

“For an American government that is willing, even it seems anxious to conquer Greenland, a challenge to Canadian sovereignty doesn’t seem that far off anymore.”

For Obed’s part, he sees the “ground shifting,” and challenged the Canadian government to shift its thinking in how it approaches the sovereignty question in both practical terms and diplomatically.

“We’re ready for this moment, but we need allyship, and we need people who are willing to think about a change in the way you think of this country, a change in the way you think of diplomacy, and also a change in the way you think about who belongs here and who is just visiting,” Obed said.

–with files from Global’s Heidi Petracek

Read the full article here