In this episode of Tax Notes Talk, South African Revenue Service Commissioner Edward Kieswetter discusses his tenure leading the agency and the country’s position in the modernization of the international tax system.

Tax Notes Talk is a podcast produced by Tax Notes. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

David D. Stewart: Welcome to the podcast. I’m David Stewart, editor in chief of Tax Notes Today International. This week: righting the ship and setting a new course.

At the end of October, the podcast team traveled to Cape Town, South Africa for the International Fiscal Association’s Annual Congress. While there, we recorded several interviews — as well as penguins at Boulders Beach — which you heard at the beginning of the episode. We’ll be releasing the interviews over the next month.

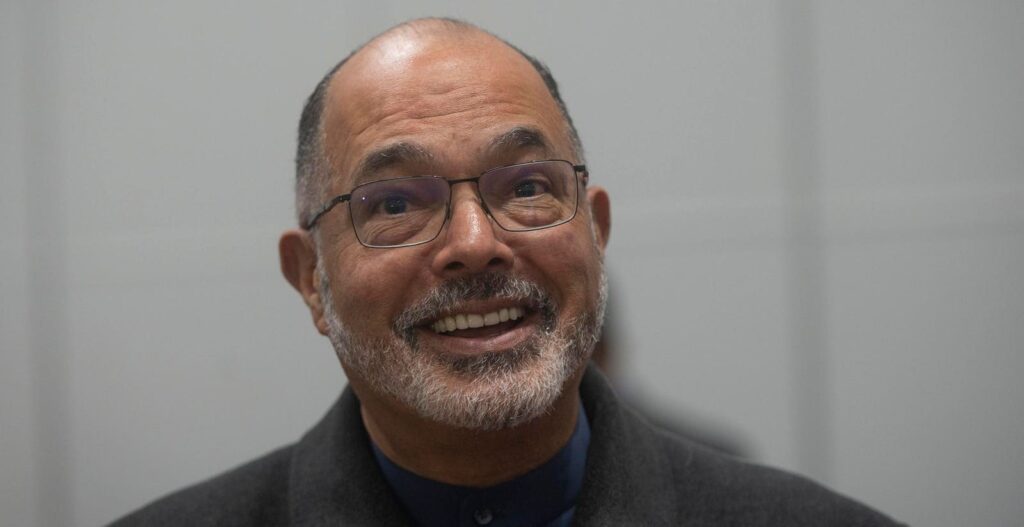

This week’s episode features South African Revenue Service Commissioner Edward Kieswetter. Commissioner Kieswetter has been leading SARS since 2019 and is also the chair of the World Customs Organization, the co-chair of the OECD Africa Initiative on Tax Transparency and Exchange of Information, and deputy chair of the Africa Tax Administrators Forum. Additionally, he’s a member of the Tax Notes International Council of Eminent Persons.

Our discussion covers everything from his tenure as commissioner to how South Africa is approaching tax on the world stage. One note before we get to the interview, since we had to leave the studio for this, the audio may sound a bit different than our usual interviews.

All right, let’s go to that interview.

Joining me now is South African Revenue Service Commissioner Edward Kieswetter. Commissioner, welcome to the podcast.

Edward Kieswetter: Thank you and thank you for having me.

David D. Stewart: I’d like to start off by talking a bit about your work at SARS. You came in shortly after somewhat of a scandal, and I suppose you needed to rebuild trust in the agency. Can you tell me about what you did, like what actions you took as you first came in?

Edward Kieswetter: Thanks, and I mean, the first point to make, since you raised it, is the state of SARS when I came in in 2019. As very well documented by a commission of inquiry that was established by the president to establish what had happened at SARS reported that SARS had suffered a significant breach of governance and integrity and that this was done as a deliberate and intentful endeavor by the political principle and the erstwhile commissioner who was appointed to serve a narrow and corrupt intent.

The result of which also meant that the organization became suboptimal in giving effect to its mandate to collect taxes, facilitate legitimate trade, and improve compliance, in that trusted organizational arrangements were dismantled. Over 3,000 staff over a quick period left the organization because they no longer felt this was a home, or they were either coerced to some questionable ways to leave. And about another 60 very senior professionals, leaders, were completely marginalized. Trust between leadership and the employees had been broken and revenue and tax morality and public trust starts to decline. So that was the state of SARS.

Coming in requires firstly an uncompromising resolve to take on this role, firstly, with a deep sense of privilege. Leadership is an inordinate responsibility to which none of us have. We are called to lead, and when we are, it is a huge privilege to do so. But also a clear resolve to act without fear, without favor, without prejudice to do the work that the law requires us to do. I often say the president appoints the commissioner, but once appointed, the commissioner is not beholden to the president. He’s beholden to the law and the dictates of his or her conscience. And so, the first thing I did was to be unambiguously clear to the staff where I stood on matters of substance.

So by 12 o’clock on the first day, which by the way was a public holiday in South Africa, every employee received a personalized letter from me. And when I walked in at about 9 o’clock, I had written the letter and the small team who supported me said it can’t be done. And I said to him, “Don’t tell me that. We put men on the moon. We split the atom. You tell me you can’t write a personalized letter that is mail-merged in our employee database? Go and sort it out and come back and tell me when are we going to do it, not whether or not we’re going to do it.”

So they scurried away. But it was also an important way for me to tell them that we are not going to just accept things because it’s never been done. And so, by 12 o’clock a letter went out and the letter said, “Dear Edward, today I take on this privileged role to be the commissioner of SARS. I really feel privileged and blessed, but here’s what you need to know about me.”

And four things. The first is I was clear where I stood on state capture. I said, “It’s real. It was driven by corrupt intent, and it had really undermined the organization, and if any of you do not believe it, you are either complicit or you are indifferent and either two conditions is dangerous. Please come and talk to me if you find yourself in that space.”

The second part of the letter was to say, “These are the things that I will do and you can expect of me and you can hold me accountable for.” The third component was having stated my office, I said, “Now these are the things I will expect of you and hold you accountable for.” Then I ended my letter by saying, “And if we do this together, this is what we will achieve.” And I set out what we would achieve. So that letter obviously connected me to everyone before I even started, and people started writing to me and say, “Thank you for their letter. We are so excited and looking forward to meeting you in person.”

And so, that started my first — that was day one. On day two I invited the top 60 to 70 leaders into a room, basically same message as my letter, but then I said, “You’ve been here as leaders, some of your names are mentioned in the report. I want all of you to know that I don’t have a hit list. I’m going to do my work, and as I do, I’ll get to know you and until then, assume you are here. Don’t assume that I’m targeting you or anyone. I will evaluate you by your performance. And for those of you whose name is mentioned in the Nugent commission report, I’ll have a one-on-one with you today still.” And so that’s how I started.

Long story short, within three months, agreed that about six of the senior leaders would leave, disbanded the senior executive and reconstituted it, started walking our offices, the front lines, engaged with people, got to know their true trauma, the true hurt and emotions and just connected with people, listening.

And after about six months, introduced a new strategic intent, introduced a new organization arrangement and then spent the next few months to put that in place. And that’s what started it, a clear vision to be a smart, modern SARS with unquestionable integrity that could be trusted and admired. A clear, strategic intent that we would build an organization that is based on voluntary compliance and nine strategic objectives in support thereof that I said will be the guiding plank on which we will build our work, the first three objectives being the principles of voluntary compliance, which is make things clear and certain, make things easy for taxpayers, and present a credible threat of detection for those who choose to break the law. The next four objectives were those that spoke to our enabling environment. Four things we said, we will make sure we have people who are honest, hardworking, but also future-proof, high-performing, professional.

The second was we will expand and increase the use of data so that we could automate routine work and augment our knowledge work with insights from data. The third strategic objective in terms of the enabling objectives was to say, “We will create enabling technology to interface and engage with our taxpayers, our traders, and all our stakeholders. The fourth strategic objective in enabling subset was we will become resource stewards. And that was very consciously chosen because we use taxpayers’ money, and we have to give an account for it, do so beyond reproach, but also deliver efficient and effective outcomes.

The last two objectives, eight and nine, is built on the notion that we are not an island. We are part of an ecosystem, we have to work with and through intermediaries and other stakeholders to achieve our objectives. And the ninth objective was we have to work hard to earn the public trust. So clear nine objectives against which we then put subobjectives and key results, milestones, and that’s been the journey of the first five years.

We also said leadership is key, and we built over 15 months working with the top 70 leaders, developed a homegrown leadership model that speaks to three things — speaks to who we are, what we do, and why we do it, what we stand for. And it’s very detailed. It’s on our website if you’re interested.

We also said we want to have an engaging workforce and we set five principles of engagement. I call it five employee rights. We say every employee has the right to do work they enjoy. They have the right to understand the meaning or the impact of their work. They have the right to understand what they have to do to win, what winning looks like. They have the right, in the fourth place, to helpful feedback that will help them win. And the fifth right is they have the right to a fair deal. And so that’s the composite model of engagement that we built, and we set very clear focus areas for taxpayer engagement, for employee engagement, and build a focus compliance program to fulfill our mandate.

Five years later we are very pleased. We cannot declare victory yet, we have a long way to go, but we have substantively turned the organization around and cemented it for the future. So we can report, for example, that in a very sluggish economy, our revenue has grown on a compound annual growth basis of 6.5 percent. Our compliance revenue has grown by over 20 percent on a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) basis. Our voluntary compliance took a dive first but came up by 1.2 percentage points, and our trade facilitation went up by 52 percent.

The wonderful encouragement actually doesn’t come from those hard measures, but it comes from the underlying softer lead indicators. In 2019 our taxpayer service was 54 percent. We can now report a taxpayer service level of well over 81 percent. Trust in taxpayers as surveyed independently in 2019 was 48 percent. When we measured it at the beginning of this year, it was over 75 percent, from 48 percent to over 75 percent.

Attitude towards compliance went up from 66 percent, today it’s gone up by 11.5 percentage points to 77.5 percent. And our own employees, we measured pre-COVID was 61 percent engaged. When we measured it last, it went up to almost 70 percent. So all of the indicators went well.

Now when I shared with you like this, it sounds easy, but let me just assure you, it was hard work. It was grueling. Nothing grand about it. I always say to do what we have achieved isn’t one big thing, it’s getting millions and millions of little things right.

David D. Stewart: It’s one thing to get your house in order and tell employees your priorities and what you want to do. That sort of tax morale side of it, of getting taxpayers back on board with the agency, what does that take? How do you communicate to the public that this is an agency that is back on track?

Edward Kieswetter: So a couple of things. Firstly, I benefited when I joined the agency by having a public profile that was respected and trusted. I had been at SARS before as the deputy commissioner. I am known in the business world as an ethical steward leader. So I came in as a recognizable and trusted figure in the public space. And that alone was helpful because at the end of the day, the most valuable asset that we have as leaders is our reputation, our integrity.

So that helped, but I also made a few conscious decisions. The first is I manage my own Twitter then, now X account. So I put myself out there. Taxpayers can give me feedback. I don’t have a team that’s behind me that responds to the Twitter feed. I respond directly. The second thing is I talk regularly to taxpayers. I’m probably the most recognizable public figure other than the president and a few high-profile politicians.

But one of the more recognizable because I do a lot of communication, whether it is just reporting our results and our progress, whether it is doing a webinar and doing some taxpayer education or awareness raising or just walking in public spaces, talking to people. When there’s a queue in our offices on high peak days, like filing season days, I go and stand in the queues and talk to people, ask them how they are, what they’re doing, why are they here? So just being available, being accessible, putting myself out there for taxpayers to talk to me and for me to talk to them has helped.

And then thirdly, speaking the truth helps. You have to have a believability about you if you’re a public figure. People may not like what you say, but they must trust what you say.

I was, for example, asked in Parliament one day whether the president or any senior Cabinet minister has ever called me to ask me to do anything inappropriate? This is in Parliament, which is on live television. And I didn’t have to lie. I could say, firstly, I can say without any fear of contradiction that I have never received a phone call from the president or anyone to do something which is inappropriate. But more importantly, I went on to say, I would sooner resign than take an instruction.

So, it’s weird. People actually come up to me and say, “We just want to thank you for what you do.” I mean, this is the taxman. “We just want to thank you for what you do. You give us hope that we can recover from state capture. You give us hope that public institutions can function effectively.”

This morning in this article, which has nothing to do with SARS, but it has to do with how you build state capacity. And I read to you, this is a trade union leader saying the following: “So the government should seek to attract and retain skills in the public service rather than showing people the door. We are witnessing the loss of critical skills. The South African Revenue Service has shown that by appointing competent management, removing corrupt elements, filling key vacancies, and investing in the capacity of the state, society reaps the rewards of quality public services that spur economic growth. This SARS model must be followed instead of suffocating the public service.”

This is a trade union leader speaking. I mean, obviously it fills one with pride but also a sense of humility that the public sees one as a beacon of hope and people come up, they want to take selfies with a commissioner, the man who’s in your pocket taking your money. So I glibly say we take more money from people, they trust us more. Our employees are working harder, but they’re more engaged. So it’s that combination of factors which ultimately builds trust and restores confidence in the public.

David D. Stewart: It’s a fascinating journey you’ve been on. Let’s turn to the more mundane aspects of just tax administration and what you see as the greatest challenges for tax administration here in South Africa.

Edward Kieswetter: Our challenges are different challenges elsewhere in the world, by the way, so in 1997 when SARS was created, we were formally two government departments, typically bureaucratic, inwardly facing, administratively oriented, no such thing as customer service or taxpayer service. So the first phase of transformation or modernization then was about the structural merging of two formally bureaucratic departments, but the cultural reimagination of an outwardly facing taxpayer centric organization. Not a lot of technology, just a different DNA, different culture, different orientation, but also inwardly, some reorientation to build more service centers as the front line, and behind that, assessment centers to do a lot of the manual processing to provide more efficient outcomes.

In that first phase of modernization, we also went to the Parliament and publicly declared a service charter. We committed to serving the taxpayer and gave certain service levels. And then slowly, also because we’re from South Africa, so we have the whole gender transformation as well as the historically disadvantaged ethnic and racial composition, we had to also do that.

So, not only did we have to build a world-class organization, we also had to transform it in terms of representing the democracy of South Africa at the time. That was an incredible journey from about 1994 to about 2006, 2007. We actually called it Siyaka, which means building together. And our first commissioner who sadly, Pravin Gordhan — went on to become a Cabinet minister, minister of finance, and other portfolios — we buried him earlier a month ago, but he was the first commissioner. And I always say he was an evangelist of the notion of a higher purpose.

The second phase of transformation was digital transformation. So digital transformation was about transforming physical experiences to digital experiences. So let me give you an example of that. So formerly as a taxpayer you would fill out manually a tax return, attach all the supporting documents to it, put it into an envelope, send it via snail mail or a courier or person who dropped it off in our offices. We would physically open it, here and there have paper cuts and created a paradise for dust mites because we ended up with these mountains of paper that staff members had to work through, edit it, and get it ready in packs for manual assessment.

This manual assessment would then be engaged in by our assessors. They would often have to call the taxpayer for additional information to verify certain things. And ultimately an assessment outcome is produced, which tells you either you’ve been assessed and you’re OK, or you’ve been assessed and you owe SARS more money, or you’ve been assessed and we owe you some money, we’ll pay you the refund. All of that on average took six months from the time you submitted your return to the time that you receive your return. And if you were due for a refund, on average, we would give you the refund in about 50 days. Six months, 50 days.

Imagine then, I would tell you that in the future you would get your assessment in under five seconds from six months, and your refund will pay to you in under 72 hours from 50 days. And the 72 hours, by the way, is partly due to the banking payment system, not us. You would have said, “You’re smoking something.” From six months to under five seconds. Well, today we do that. And how have we done it? We’ve transformed a physical experience with digital experience.

So firstly, you don’t have to manually fill in a paper, we present you with a prepopulated return. You add whatever you think you don’t have, you attach whatever documentation you need, you submit it to us, and you get your assessment in under five seconds. Because we suck that information in, run it through a tax calculator, and then run it further through a risk engine to alert it for any risks. And then lastly, we do a fraud risk detection machine-learning capability that we run through to see if a refund is permissible or fraudulent.

So, all of that we do. That was transforming, no more paper. Ninety-seven percent paper in 2006. Today, 3 percent is paper and we terminate the paper as you walk in, you take your paper back. So that’s the second phase. Transforming physical experiences into digital experience. The next phase, the phase we have now just started and are excited about, which we call SARS Modernization 3.0, is not about digitization of experience, it’s about disintermediation of experience. So we went from manual to physical, I mean physical to digital. Now it’s digital to disintermediation.

So imagine you wake up and taxes just happened. You have to do nothing. In fact, our ambition is once a year we want to send you a thank you note and say, “Thank you for your contribution, your obligations are fulfilled.” Now, that’s not far-fetched because we already did that this year for 5 million taxpayers. Five million taxpayers didn’t even have to submit anything to us, which was the second phase of transformation. For 5 million individual taxpayers and the journalist who interviewed me just before, he actually thanked me because he was one of the beneficiaries of ours.

So using third-party data from banks, from employer payroll information, from retirement funds, from medical administrators, then having access to the Deeds Office for title deeds to the stock exchange, to the motor vehicle registration register, to the population register. We suck all that information, 150 million demographics we suck in. We build a picture of who you are using the data. We then from that look at your income, your deductions, your financial transactions, and we use that, including, by the way, if you have overseas bank accounts through the automatic exchange of information and common reporting standards protocol that we have with other OECD countries. And so we do all of that on your behalf. We then present you with this SMS to say to you, “By the way, your assessment is ready, log onto your phone. If you like the output, you don’t have to do anything, we’ve done it for you, and you get your refund 32 hours later.”

That’s disintermediating as opposed to digitalizing the experience. And why are we able to do that? Because we’ve now moved from the age of digitalization to the age of artificial intelligence using data science and AI. And for us the future is about that. It’s the same stuff that my peers, we’re meeting soon in Athens at the OECD Forum on Tax Administration plenary and this will be the conversation.

So if you look at “Tax 1.0,” it is about taxpayers submitting information to us, making declarations to us, and then us computing an assessment outcome and implementing it. “Tax 2.0” is increasingly not requiring you to submit information, us using third-party data information and computing the assessment outcome without you having to provide us with the information.

But both “Tax 1.0” and “Tax 2.0” are still retroactive. It’s still the past. We are now assessing you for the previous fiscal year, and we’re doing that three or four months into the new fiscal year. “Tax 3.0” is about real-time assessment.

So truly is every month you get a statement from us that says, “Dear Sir, Dear Madam, you’ve earned so much money. This is your expenses, this is your outcome. So we’ll send you a tax account, a statement every month without you having to do anything.” So in real time, you are being assessed. So at the end of the year, unlike now, we do a retrospective assessment and give you a once-a-year outcome. You’ll get an outcome every month, which is offset pluses or minus, and the end of the year you’ll just get an account.

So that’s “Tax 3.0.” What makes it possible is because we went from physical and paper-based to digital and information-based to purely data science and AI-driven.

David D. Stewart: I want to pivot here at this point because we’re talking about a very frictionless system that you’re discussing setting up to a system that is perhaps more “frictionful,” maybe, if that’s a word. You mentioned the OECD. We’re going to turn to the wider context here and South Africa’s position in the modernization of the international tax system.

The OECD has been working on the two-pillar project for the digital economy, and part of that is the inclusive framework. Can you tell me about how your experience has been of working with the OECD and the plans that they’ve come up with?

Edward Kieswetter: So, very interesting, I have this unique position that I’m the commissioner of the South African Tax and Customs Administration, and as such, I’m a member of a BRICS country, and I’m a member of the developing world, a member of the Global South. At the same time I am the chair of the World Customs Organization, which has 186 member countries — East, West, North, South. So, I wear an international hat.

And then I’m also the vice-chair of the OECD Forum on Tax Administration and play other leadership roles in the global forum. So, I have the vantage point of being in the North and the South, East and the West, occupying a global chair. So, that together with my general personal philosophy of the world — that we need a more inclusive world, a more equitable world, a world that seeks to close the divide between the haves and the have-nots — I see taxation as playing an important role to breach those divides to heal a broken world.

Sadly, our world is polarized, and if you listen to a lot of the political narrative, that’s not going to go away soon. In Africa we have a saying that when two elephants fight, it’s only the grass that gets hurt. The elephants will survive, but the grass might not. So I come from a place where I do have a global vantage point, but I also come from a deeply underprivileged background, both economically, politically from a South African system of oppression where I was the oppressed, which has calibrated my DNA in the way that I use all of my roles to bring the world together as opposed to amplifying our differences. And so, I know it sounds a bit evangelistic, it sounds spiritual or philosophical, but I think all things that manifest ultimately in policy, when in practice starts in consciousness.

And so, the big need to reconscientize the world towards the world that we want to create for our children, because I think we are too old, we’ve got to move on. But I have hope for our children. Within the context therefore of that broad, almost philosophical, but also principled stance, I advocate the following — that domestic resource mobilization for every country, it may not be as evocative as singing your national anthem, whether it’s “The Star-Spangled Banner” or “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika.” It may not be as colorful as our flags, as symbols of national identity, but ultimately domestic resource mobilization is the anchor on which sovereignty is built, not your flag or your national anthem. It is the domestic resources. So countries define themselves by their ability to take care of their people, and they need the resources to do that. And therefore, for me, taxation is the lifeblood of any self-respecting nation.

In this regard, the contestation for taxing rights is real and should not be surprising. It’s going to intensify. Why? Because of the forces that I’ve shared with you now of amplifying differences, of increasing the divide, however you may define the divide. And so in formulating international tax laws, we have to not think about it as technical instruments that manifest its laws and regulations and the issue of taxing rights, but we have to think of it as strategic instruments to achieve the world we want. Now in that regard, having said that I wear all these hats, it is true and to some extent has justification that the OECD is often seen as a voice club, as a voice for the privileged, as a voice for the developed world, which is why there’s a murmuring from the Global South and a popular broadening of BRICS. Because actually if you think about it, the Global South and BRICS represent more than half of the world.

Now, I don’t become political about this or ideological about it because I would make a bad politician, and I’m certainly not an ideologue. I’m a pragmatist. The only “-ism” I will ever ascribe to is pragmatism. And it is about what outcomes you want to achieve, not what ideology you want to subscribe to. So we shouldn’t be surprised that the United Nations has very eloquently and clearly manifested in the 2023 Convention on Taxes saying, “The OECD does not represent all of us. We need a different institution that speaks for all of us that is more representative, that is more inclusive, and that has as an objective to be more equitable.” Tax Justice International says, “For example, that if we were to just assign taxing rights and then build the capacity for administrations to administer those rights, then in the developing world you will not need aid because the taxes due would fund government.”

Obviously corruption and all of that is an issue. But putting that aside, taxing rights supplies the resources and it needs to be administered. But now no country is a fiscal island. Taxing laws are not any more about domestic resource mobilization. It is now actually about understanding. Most countries have in the last two decades moved from source-based to residence-based tax, worldwide taxes, so that if you are tax resident in a country, no matter where you are, your tax obligation is to that country.

But now in a world that is increasingly more mobile, where countries are handing out passports based on economic investments and other criteria, individuals and companies can arbitrage that. Countries through policy differentiation, create tax havens, some of which are aggressive and hurting countries that are not. So international taxation has to be more equitable and has to seek to achieve some of those higher-purpose objectives.

And therefore, I am a strong proponent to say that this narrative will not go away, it will intensify. But I am also balancing that by saying this is not an either/or. To the credit of the OECD, they have far more deeper technical competency both in law and in financial disciplines, which is really the intersection. Taxation comes from those things.

Taxing laws, understanding how economies work, understanding how law and accountancy merges is what produces the fiscal resources. So, we shouldn’t lose that. At the same time, it is true that the United Nations is a more inclusive with the veto rights of the U.S. or other alliances and alignments, but we have to either say that the decision posts the League of Nations to ease our vehicle for global peace, for global equity, or it’s not. And if it doesn’t behave like that, it will be replaced like the League of Nations.

No institution stands forever, and especially if it doesn’t serve its purpose. So, I’m a strong proponent for saying take the best of both worlds. Take the broad representativity of the United Nations, the broader inclusivity thereof, bring the U.S. along so that it doesn’t abuse its veto rights, and then incorporate the best of the OECD. So, I have proposed in a presentation I made at the London Convention on Taxation, I propose a substantive partnership model and for me, a substantive partnership model, I’ll share that in the pause, will have the following four elements. First, it’ll establish joint committees and working groups from both of these platforms, the OECD and the U.N. And already we have membership that sits on both bodies. So, it’s not as if there is a competition of two completely separate institutions. Every member who is an OECD member is also a United Nations member.

So, established joint committees or working groups that includes representation from the OECD and the United Nations working group from member countries of both the Global South and the Global North. And these working groups should focus on research, on drafting, on proposing international tax policies, and of course develop a basis for skillful negotiation around these interests, around these issues, placing common interests at the heart, not partisan interests.

The second is sharing of resources and expertise. It is undeniable that the OECD have significant technical expertise and significantly more resources, especially from the developer. But don’t use your privilege and your resourcefulness to bully those who don’t have it and to coerce them. Like, this is my ball. If you don’t want to play by my rules, I’ll leave and take my ball away with me as little boys do. Girls would never do that, I’m sure, but little boys do. So create a platform where all of the resources are pooled, but again, to serve a common purpose, not a narrow purpose.

The third principle for substantive partnership is capacity building and technical assistance. And as I said and often do, policy is only as good as administration. You can have the best policies. If you can’t administer it, it will not have its policy intent. And so develop joint programs that is aimed at building administrative capacity, the capacity we spoke about earlier on in developing countries so that they can administer their own laws. The concern now with pillar 1 and pillar 2 is less about its design and more about the arbitrage opportunities it will present that will, again, disadvantage developing countries who don’t have the capability and advantage developed countries who do. And then the last is, and I’m very strong in this, is balancing consensus decision-making with evidence-based decision-making.

Very often political actors do what is politically expedient and palatable, even though the evidence doesn’t always support it because political parties are voted into office, and they need to make sure they win elections. And so, there’s this populism around there, whereas taxation and the equitable distribution of your sources, it’s not a political thing, although it has political currency. It’s about feeding people, building schools, building roads, advancing science, expanding production bases, and educating the next generation.

Those are technical and societal issues, and they need evidence-based decision-making, not consensus decision-making. Because we know as your country and my country have proven, democracy may be our most available and legitimate form of putting governments into power, but democracy is not perfect because the majority isn’t always right.

David D. Stewart: This has been a great discussion. Commissioner, thank you so much for being generous with your time and joining me.

Edward Kieswetter: It was my absolute pleasure.

Read the full article here