Diane Keaton’s unexpected death on October 11, 2025, at age 79 spurred an outpouring of grief and celebration of a woman who touched countless lives through her work. Keaton starred in beloved movies such as Annie Hall, The First Wives Club and Something’s Gotta Give — the kinds of movies that many grow up with and love to revisit when the right mood strikes.

But in the days that followed, her death also prompted more serious conversations about the parts of the late actress’ life that weren’t quite as universally loved, such as her longtime friendship and support of once-boyfriend Woody Allen. The director, who married his ex-girlfriend Mia Farrow’s daughter Soon Yi Previn in December 1997, was also accused of sexually molesting his daughter Dylan Farrow, who he adopted with Mia.

As Keaton, who adopted her own daughter and son when she was in her 50s and who famously championed her decision to remain single for most of her adulthood, was celebrated for her feminist views and unconventional choices, many struggled to square their perception — or perhaps projection — of who they believed she was with who she might have actually been.

That response isn’t unique to Keaton’s passing, Dr. Wilsa Charles Malveaux told Us Weekly by phone call, and it’s also a deeply human response that’s based on “not just the movies and the roles” a celebrity like Keaton is portraying, “but even just what they let people see.”

Because it’s easy to form a parasocial relationship with the actors, artists, musicians and athletes that so many of us admire, it’s sometimes more difficult to remember that public figures so often live a dual life: “You have the person, the fuller, actual human being — the other half of the reality of who they are — that we don’t normally get access to,” Malveaux also said. “I think people get caught up admiring, and in some cases, idolizing, the persona and forgetting that it’s still a person. And nobody’s all good or all bad. We all have flaws.”

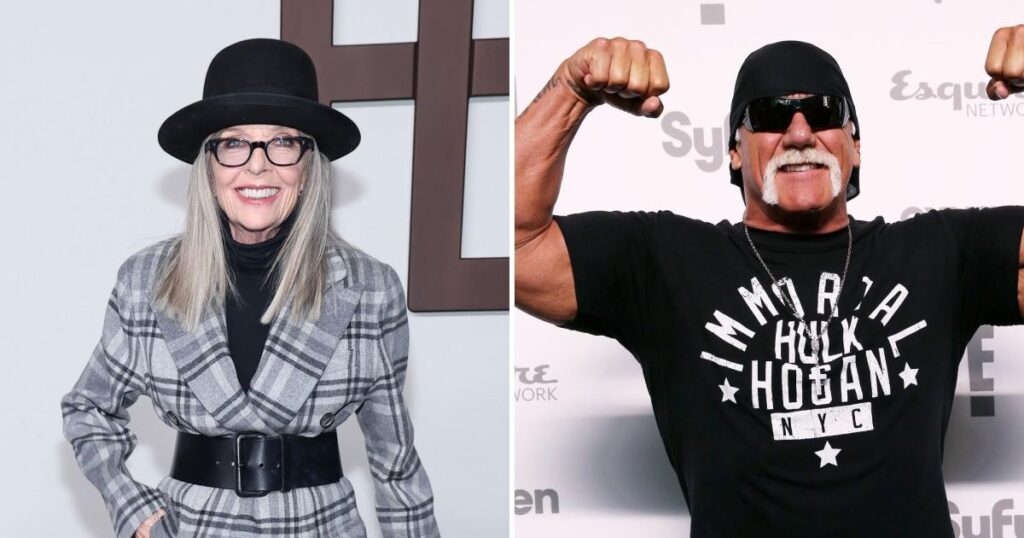

This dynamic was on display following the deaths of Hulk Hogan, who died July 24, 2025, at age 71, and NBA star Kobe Bryant, who died January 26, 2020, at age 41. Both men were largely celebrated in the immediate aftermath of their deaths, but, like Keaton, inspired larger conversations about their complicated histories in the days and weeks that came after.

(Hogan used racial slurs to describe daughter’s ex-boyfriend in 2007, and said in the same conversation that, “I am a racist, to a point.” He later apologized for using the term. Bryant was charged with felony sexual assault in July 2003; the criminal case was dismissed the following year.)

Perhaps one of the more confusing realities that many fans go through following the death of a person with a complicated legacy is that there are often other famous people — typically who are also deeply admired by the public — who come out to defend the recently deceased. It can make one question one’s own perceptions and beliefs.

“In the case of Diane Keaton supporting Woody Allen, we know what has been said about him from his daughter and from his ex-partner,” Malveaux said. “And there’s definitely a need an da push to believe sexual assault survivors. We don’t know what his relationship with Diane Keaton was, but it wasn’t just some random colleague that she was supporting.”

She continued: “There are people and other celebrities, too, that believed him when he said he was innocent and that he didn’t do it. We are kind of judging things with the court of public opinion and based off the information we get with the media, social media, and the press — but that’s not the whole picture, so it’s really hard for us to know [how to feel].”

According to Malveaux, this is the point at which cognitive dissonance plays a major role in what a person decides next. “So, basically, you have two conflicting ideas: you believe this person is a good person and they fit your moral values — but then you find out they are associated with a heinous crime. Those two things don’t mesh well in your brain and they cause you discomfort.”

The result is usually one of three things, she added. A person will change their beliefs to suit the new reality as they now understand it, or they’ll decide “they don’t think this is a good person anymore.” With this solution, “those two things are not in conflict” anymore.

Some people will also choose to “ignore the part of the idea that’s problematic to them. They’ll just not pay attention to the allegations, for example, or they’ll avoid situations that might highlight where those two things come into conflict.”

This pattern of behavior is especially relevant when considering the lives and legacies of Keaton, Hogan, and Bryant. For many, Keaton will never stop being an incredible actress and model for women, despite her support for a man who allegedly harmed a woman. Hogan will also be a wrestler who inspired others — including Black wrestlers such as Kazeem Famuyide — to pursue the sport, despite the racism he admitted to. And Bryant, the father of four daughters and coach to many young girls in his later years, will also always be the man accused of sexual assault.

Ultimately, this is the point where the age-old question comes into play: is it possible to separate the art from the artist? I personally have two Harry Potter-themed tattoos that I got in 2012 and 2015, respectively — years before author J. K. Rowling first made her anti-trans comments. I consider myself a strong ally to the LGBTQ+ community, and have often wondered if I should adjust the tattoos in some meaningful way. But they’re still there, because there’s part of me — the part that first picked up Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone in 1999 and was introduced to a world that carried me through challenges and triumphs for years — that still loves the series and everything it has brought into my life.

Perhaps one path toward mitigating the warring sides of this conversation is understanding that when we celebrate a celebrity, we are not really celebrating that whole person. “We have to recognize how much we’re putting on the public image and the persona” that someone projects, Malveaux told Us. “We have to recognize that even though we might fall in love with the persona, they’re still a person, and we can’t be surprised if something comes out that doesn’t align with our values.”

Most crucially, she also said, “We must recognize that [in any situation] we don’t have all the information. As much information as we do have access to, we don’t have it all.”

Ultimately, it’s up to each of us to square our personal values with the ways we consume pop culture and who we individually look up to, celebrate and admire. For me, that has meant not engaging directly with Bryant’s legacy but happily speaking to some of the now-young women who he worked with; it also means that I’ll probably keep my Harry Potter tattoos and will definitely still watch a Diane Keaton movie from time to time (I’ve never been a wrestling fan and have no interest in becoming one). That’s something I’m okay living with for now — and it’s something that I, and all of us, always have the capacity to change in the future if that’s what we decide to do.

Read the full article here