A few months ago, I pulled out a kids’ book for my seven-year-old to read to me.

She opened the first page, shook her head and handed it back.

“I can’t read this,” she said. “It’s in cursive.”

First, I was shocked. How could my child, a proficient reader, not recognize what — to me — was relatively simple, joined-up lettering?

Then, I got angry. Because this is what happens when you no longer teach children to write in cursive.

Once considered a basic, fundamental skill, this was phased out back in 2010, with the introduction of the controversial Common Core curriculum.

But now, for example, because my kids don’t learn it, I can’t write letters or even short notes to them in my own handwriting — something my parents completely took for granted. Instead, I have to slowly and painstakingly write in print instead, to make sure they’re able to read it all.

And I wonder — what on earth will they do when they’re older, and are asked to sign their names? Will they even understand the concept of an actual signature?

My obsession with cursive’s slow death in the culture most likely seems crazy to my children.

After all, we live in a technology-driven world. They would likely argue that they need to know their way around a computer more than they do a pencil.

I couldn’t disagree more. Writing properly and being able to read more than just block letters remains an important life skill.

In one of his final acts as governor of New Jersey, Phil Murphy tried to reverse more than a decade of failing our kids on this front — signing legislation on Monday that will require students in third through fifth grade be taught cursive.

His argument, which had me cheering from across the Hudson River: This will help pupils with basic tasks, later in life — such as opening bank accounts and signing documents.

Myself and many other letter-minded New Yorkers are frustrated to have nobody in government advocating for us — how have we been letting this go on for so long?

I’ve heard from more than a few parents, voicing disappointment that their children can barely write legibly — one even sharing photos of their son’s writing in first grade versus the seventh grade, which showed almost a degradation in legibility of his handwriting.

“We were lucky to have my eldest learn cursive in third grade. I recall how wonderful it was to see the neat handwriting on his projects on classroom walls when I would visit school,” the parent shared.

“After Covid, unfortunately, both my children only worked on Chromebooks and mostly have in Google classrooms,” she explained.

“Rarely do we see any projects written out anymore. When I ask my children to write birthday or thank you cards. I see their penmanship has deteriorated, which makes me sad that schools are not teaching cursive and proper penmanship anymore.”

This is a problem that is unique to America — most developed countries, from South America to Europe and the United Kingdom, are still teaching their children cursive.

And as someone who has raised two kids across two continents and has seen the situation from multiple sides, I have seen first hand that the United States has fallen behind.

My eldest daughter spent the first five years of her life in the UK, in London, where kids start school a year earlier. From the age of four, the first 30 minutes of her day — every day — were spent practicing lettering.

I know, because her teacher liked parents to stay for a bit in the mornings after drop off. I would watch as my daughter would be asked to write and rewrite all her letters, until they were formed correctly.

Their building block was cursive, and the attention paid to how the kids held their pencils was militant to say the least.

A year later, when we moved to New York, I arrived with a five-year-old who could read pretty capably, hold her pen properly, and write letters correctly.

Even when COVID hit, a few months later, she was able to keep writing progress up. Because the fundamentals were there. Today, she has great handwriting, much of it self-taught.

My youngest, on the other hand, has spent her entire life in the New York public system. Her school is fantastic. But when it comes to handwriting, I think the system has failed her.

There is no part of the curriculum that teaches kids how to hold their pencils properly. I know so many kids who hold their pencils in strange, improper ways. My youngest included.

She grips hers between fisted fingers, and watching her try — and struggle — to write comfortably makes me wince.

She doesn’t know how to form her letters correctly, and while her teachers have valiantly tried to help and correct her, there is truly no time in the day for them to work on this.

Hours are already so crunched — with her school day finishing at 2:35 p.m. — that the teachers already have to work so hard to get in every other key subject they need to teach. All while juggling more than 30 kids to a class.

I also see how long it takes my daughter to write a single sentence. She’s now in danger of falling behind — simply for the reason that she can’t write well, or fast enough.

When cursive is not part of the curriculum, children have to lift their pen and start again at every letter. It’s slow and also harder to write uniformly — her letter sizes are all over the place.

Of course, I get that she’s seven. I don’t expect the world from her.

But at the same time, if you compare American kids’ handwriting to those of European or British children of the same age, it’s rage-inducing.

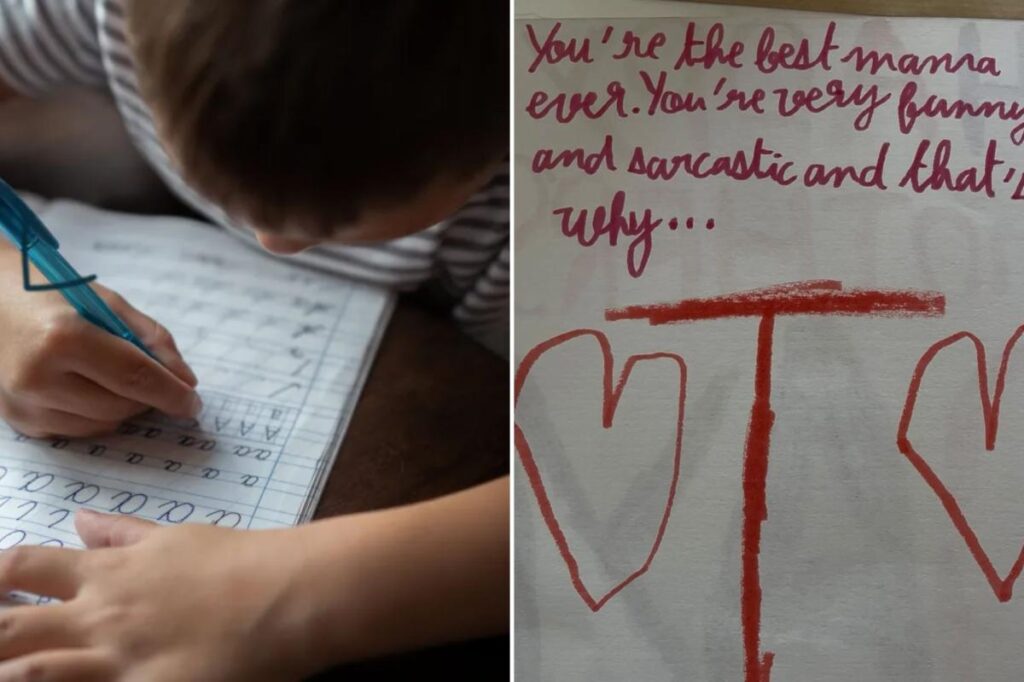

When I saw the note below that my French friend’s son had written to his American mom, aged just 7, I almost couldn’t believe it.

Lisa Wander, a handwriting teacher in London, is a vocal proponent for cursive — even recently connecting with Sharon Quirk Silva, a member of the California State Assembly, who helped pass legislation to mandate cursive teaching in the Golden State, back in 2023.

Wander argues that “learning to form words by hand is an essential building block for learning to use language and learning to think. Handwriting activates a specific part of the brain, which researchers believe is important for learning and memory.

“I have read a number of studies that prove that children who spend time working on handwriting are better able to produce clear and coherent communication, show better quality of writing and have better thought and organisation skills as handwriting helps establish the neural patterns in the brain that are needed for learning,” she notes.

She also highlights how vital good handwriting is to confidence and good grades.

“In my own experience,” she told The Post, “I see that children with poor handwriting are usually aware of their difficulty and their untidy handwriting can make them feel uncomfortable and isolated, sometimes even depressed and frustrated as a direct result of poor writing skills.

“Once these skills are taught there is an enormous difference in confidence and self-esteem.

“Handwriting also helps the flow of ideas and thoughts in a way which keyboarding doesn’t. Children who write their revision notes generally do better than those who don’t. Why we would deprive children of this possible advantage escapes me! For me this is key.

“Plus, those who have difficulty with the quality and/or speed of their handwriting are often at a disadvantage in the high-paced classroom setting.”

It’s a message Mamdani and Hochul should listen to. Literacy and math rates across the Empire State remain disturbingly low.

Nearly half of young New Yorkers statewide, in grades 3-8, are still missing the mark on standardized math and English exams, according to newly released data.

And anything that would help improve that should be prioritized.

Cursive, to me, is not an optional extra. It’s a core part of education, and a life skill, that frees up children’s creativity as well as their academics. And it’s time to bring it back.

Read the full article here