In harbourside Wellington, New Zealand’s capital, the nation’s library is just metres from its parliament, its court of appeal and the city’s biggest cathedral. Step inside the library and you’ll find a treasure box – or, at least, a room inspired by a traditional Maori one, its curved walls clad in native timber from fallen rimu trees, its lights dimmed. The treasures on show are documents, including what historians call the most significant in the nation: Te Tiriti o Waitangi, or the Treaty of Waitangi. The display case faces towards the parliament. “It’s a deliberate design feature so that Te Tiriti watches the foundation of this modern nation state,” says curator Stefanie Lash.

The nine time-worn pages contain the signatures of more than 500 Maori chiefs and British naval officer William Hobson, who in 1840 entered into an agreement for the Crown that aimed to provide for British settlement while protecting Maori interests. “This is a piece of parchment that is a symbol of hundreds of years of race relations and national history,” says Lash. “Time collapses on to the face of that parchment. It’s an incredibly powerful object.”

The Treaty of Waitangi is displayed to the public in a room designed like a Maori treasure box, in the He Tohu exhibition in the National Library. Credit: Courtesy Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kawanatanga

Every signature tells a story. In 1824, Kahe Te Rau-o-te-Rangi, one of at least 17 women who added their names, was on Kapiti Island, north of Wellington, when she learned an invading party was on its way. She lathered herself in shark fat, powdered in red ochre for insulation and – with her child attached to a raft of dried reeds and tethered to her back – swam the length of the island, to stay in its shadow, then dashed across the channel to sound the alarm. Years later, she was the fourth of a cohort of 40 leaders in one treaty signing, indicating her prestige.

Still, the treaty was not honoured for more than a century. It’s just one of many agreements the British made as their colonial parties encroached on lands that Indigenous nations presided over across the world. In Australia, the country’s first formal treaty between a state and First Nations people is about to be debated in the Victorian parliament, the culmination of nearly a decade of work to forge a framework.

In NSW, meanwhile, a treaty commission is consulting Indigenous communities across the state about their desire for a treaty. “There are unique aspects of Aboriginal culture yet also shared experiences with other Indigenous and cultural groups globally,” says NSW Treaty commissioner Aden Ridgeway. “For Aboriginal peoples in NSW, the central question is not abstract or academic, it is deeply personal: ‘What is the benefit for us, and how will it meaningfully improve the lives of Aboriginal people’?”

Indigenous treaties, whether historical or modern, are all born from unique circumstances. Yet, they can also offer precedents for others. How do Indigenous treaties work in other countries? Have they succeeded? And what are they still contending with?

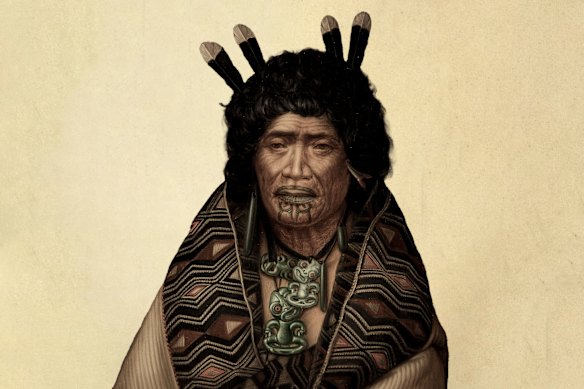

Waitangi Treaty signatory Te Rangitopeora, songwriter and leader in 1863.Credit: Gottfried Lindauer, digitally treated

What is an Indigenous treaty?

In the 1600s and 1700s, Indigenous people in the Northeastern Woodlands, an area that today takes in New York and the Great Lakes stretching into Canada, exchanged items to represent agreements. The best-known were leather wampum belts, beaded with shells from the Atlantic coast. “A wampum belt was given to actually prove or support the spoken words,” Jonathan Lainey, curator of Indigenous cultures at McCord Steward Museum, tells us from Montreal. “What you said could be many things, of course. So sometimes people were exchanging wampum belts to support their request, or to support their promise, or to support their engagement.” The exchange became so common that in 1760, the British gave their own wampum belt, with a hatchet patterned on it, to make a peace agreement with the Wendat Nation, today located in Quebec City.

The wampum belt with a hatchet on it that the British gave the Wendat Nation in Quebec in 1760. Credit: Courtesy of the McCord Stewart Museum Montreal

The earliest agreements between the British Crown and people in the so-called New World were aimed at building relationships. “Indigenous nations saw treaties as relational documents to find a way to let the newcomers into their ongoing and existing networks of reciprocity and exchange,” says Harry Hobbs, an associate professor of constitutional law at UNSW and co-author of the book Treaty. Over time, however, treaties became more about dividing land and resources. In Australia, Britain didn’t sign treaties. The occupation of land was justified under the doctrine of terra nullius, which the High Court found to be a legal fiction in the 1992 Mabo case, which recognised native title.

‘The central idea is that the parties are coming to that moment of agreement because they see some mutual benefit and enter into this new relationship.’

Carwyn Jones, Te Wananga o Raukawa university

Early treaties recognised some level of sovereignty in parties such that they could be “treated” with. In the United States, treaty-making stopped in 1871 because a law was passed such that Indigenous tribes were no longer considered sovereign nations, although different types of agreements were negotiated; and Canada also paused treaty-making in 1923. Today, these first waves of treaties are known as “historic treaties”. “They were written much more at the level of principle rather than detail,” UNSW’s Hobbs says. “That means [today] there’s a huge amount of disagreement about, are they actually being interpreted correctly? Are they being enforced or not?”

In the 1970s, a push for legal mechanisms to resolve Indigenous land claims gained traction across Canada, the US, New Zealand and Australia. This led to historic treaties being re-examined and the first modern treaties in Canada. In 2007, the UN adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which includes “the right to the recognition, observance and enforcement of treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements concluded with states or their successors”. The exact differences between these types of agreements can be difficult to pin down, says Sheryl Lightfoot, the vice-president of the United Nations Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, but the word treaty “tends to invoke a certain status of historical self-determination or sovereignty of people”.

In any case, for these agreements to work, Lightfoot says, there needs to be mutual – not imposed – agreement between parties and there has to be understanding of who holds what jurisdiction over certain issues and where those responsibilities apply. “They are, essentially, a modern agreement of governance responsibilities.”

Still, the “old-fashioned” acknowledgement of a new relationship remains key. Carwyn Jones, from the Maori laws and philosophy program at the Te Wananga o Raukawa university, says: “The central idea is that the parties are coming to that moment of agreement because they see some mutual benefit and enter into this new relationship. That’s a really important foundation of treaties.”

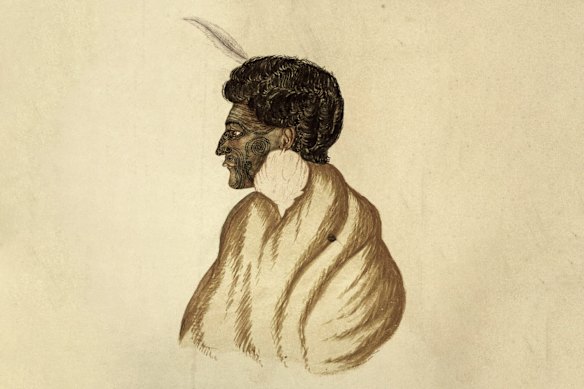

The chief Te Rauparaha was one of more than 500 Maori leaders who signed the Treaty of Waitangi in the 1840s. Credit: Copy after Isaac Coates via Alamy

How does the Treaty of Waitangi work?

The Treaty of Waitangi had three main provisions: it allowed the British Crown to establish government, it preserved Maori people authority over their own affairs, and it gave them what is considered today to be citizenship but based on cultural equality. ”It was an agreement where there were different spheres of authority, and it would develop according to those three presumptions,” says Dominic O’Sullivan, professor of political science at Charles Sturt University.

But in 1877, Supreme Court Chief Justice James Prendergast infamously ruled that Waitangi was a “simple nullity” and unenforceable in domestic law. For over a century, New Zealand governments widely ignored obligations under the treaty. In fact, no one knew where the document was. “Between the years of about 1865 and 1908, or thereabouts, it’s more or less unaccounted for,” says National Archives manager Stefanie Lash. The treaty sheets, especially two made of sheepskin, have been gnawed by rodents. “When people think of the treaty, they would think of that big Waitangi sheet that has clearly sustained some real damage. To me, the way that sheet looks and the damage it’s sustained speaks to the way that the treaty relationship has played out over the centuries.”

From the late 1960s, a wave of Maori activism gained momentum, peaking during the Maori land march in the mid ’70s when 5000 people joined a month-long trek to parliament across the North Island. It prompted the creation of the Waitangi Tribunal, which turned 50 last week, to investigate claims of Crown treaty breaches after 1975. Ten years later, the tribunal’s scope was expanded to include breaches back to 1840. Over time, its findings have “contributed so much to our understanding of who we are, what’s happened here,” says Lash. Outcomes have included laws to establish Te Reo Maori as a national language (phrases such as “Kia ora”, or hello, are often part of everyday conversation) and the setting up of the public broadcast channel Maori Television Service in 2004.

Many tribunal cases have involved the issue of sovereignty. There are two versions of the treaty: one, in English, says Maori people ceded to the Crown “all the rights and powers of sovereignty” yet the other, in Maori, uses the words “Kawanatanga” (meaning governance) and “Tino Rangatiratanga” (highest chieftainship), which Maori people have understood to mean they kept authority to manage their own affairs. (Only 39 of the more than 500 Maori chiefs signed the English-language version, leading some to believe they were at odds with it.) The tribunal as well as courts, elected officials and local communities continue to reconcile these differences in the texts today.

What form does redress take? In the 1990s, the conservative National Party led a policy of engaging in negotiations with groups of Maori tribes (known as iwi or hapu) to deliver redress. A landmark settlement, the Sealord Deal, delivered $NZ170 million ($150 million), which enabled Maori people – who make up some 17 per cent of the population – to have a stake in the country’s biggest fishing company and control over about a third of the country’s fishing quota. (The Treaty of Waitangi states Maori people are granted “full exclusive and undisturbed possession of their Lands and Estates Forests Fisheries”.)

‘It’s a product of its time … But it shouldn’t stop us intelligently applying what we understand the core of the promise was.’

Andrew Little, fomer minister for Treaty of Waitangi negotiations

So far, there have been more than 80 tribunal settlements totalling more than $NZ2.6 billion ($2.3 billion). “That’s one of the critical things that Maori wanted, was restoration of the economic base,” says Andrew Little, who was minister for Treaty of Waitangi negotiations in the Labour government from 2017 to 2023. “So there’s fishing, farming, a lot of forestry, and tourism is a big deal. Just north of Christchurch, you’ve got the whale-watch business there. Also on the central North Island, Rotorua, Maori tourism is a big deal.” Still, restitutions are a work in progress. Says O’Sullivan: “These things are significant, but people wouldn’t necessarily call them wins, I don’t think. They would call them part of the process of restoring rangatiratanga.”

Andrew Little, a former minister for Treaty of Waitangi negotiations: “The treaty represents this incredible dream.”

The treaty continues to spark political debate, too. In 2024, David Seymour, leader of the right-wing ACT Party (which is part of the coalition government) argued the treaty created an inequality in people’s rights and introduced legislation to redefine its principles and put them to a referendum. The bill led to the nation’s biggest protest, of 42,000 people, prompted 300,000 written responses (the most the government had ever had) and was defeated in April with just 11 votes in support.

The vote, says Little, was another turning point that proved voters and political leaders expected the treaty to be respected. But he acknowledges the way the treaty is written is broad. “It’s a product of its time. It was written kind of at a high level, and we have to apply it in a world where we have become more technocratic, and government has become more complex and sophisticated. But it shouldn’t stop us intelligently applying what we understand the core of the promise was, which was the rights and interests of Maori would be protected to enable this nation state of New Zealand to try to prosper. The treaty represents this incredible dream, and it wasn’t delivered on for the first 150 years of its life. And we spent the last 30 years trying to catch up so we can deliver on it.”

Lakota leaders attending a treaty signing at Fort Laramie in the US state of Wyoming in 1868.Credit: Alexander Gardner

How did the US and Canada do Indigenous treaties?

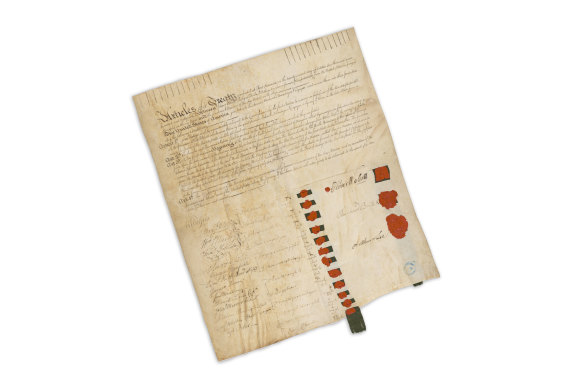

When the American Revolutionary War raged between Britain and the 13 united colonies that had broken from its grasp, the fledgling Congress saw an opportunity for its forces to attack their enemy in what’s now Detroit. But to do so, they needed both permission from the Delaware nation to cross their territory and assurances they wouldn’t be attacked when they did. It was 1778, and Congress drew up its first written treaty with an Indigenous tribe. They also made an offer they never repeated: for the Delaware nation to join the union as a 14th state (the Congress never upheld the promise).

‘These were negotiated in English to native people who didn’t speak English. So they had to trust the interpreters.’

Robert Miller, federal Indian law expert and member of the Eastern Shawnee tribe

As the US formed into a republic, it made 375 treaties with Indigenous tribes that are ratified today by the US Senate (there had also been about 100 treaties the British signed that the US didn’t recognise). The treaties included ceding of land, recognition of reservations for tribes and acknowledgment of their self-governance. Many remain problematic. “These were negotiated in English to native people who didn’t speak English. So they had to trust the interpreters,” Robert Miller, an expert in federal Indian law, tells us from Arizona State University. “What did Indian people understand they were being promised before they would sell land?” He points to a treaty that covered salmon fishing rights in the Pacific Northwest that was translated from English into Chinook Jargon (a mix of languages that helped with trade in the area) then into the tribal language. For others, bribes and signing under duress are factors thought to have been at play.

A treaty between the United States and the Haudenosaunee nations (or Iroquois League) signed at Fort Stanwix in 1784.Credit: US National Archives

US courts have set out principles – known as the Indian Canon of Construction – where ambiguity in treaties can be interpreted broadly in favour of how tribes would have understood them. In some cases, courts will accept oral history. “So literally, court trials will have elders get on the stand and go, ‘Well, my great-grandfather was at that treaty session, and here’s what he told me was said’,” explains Miller. “Normally, we call that hearsay, and that kind of evidence would not be allowed in a court. But it’s allowed in this case because you have to understand what the tribal peoples thought they were being promised.”

There are 574 federally recognised tribes (the most are in Alaska, where there are more than 228). Many of their rights have not been secured through treaties, but acts of Congress, executive orders or court rulings that interpret their sovereignty. In the mid-20th century, policies tried to end federal recognition of tribes and their land rights. Then in 1970, President Richard Nixon brought in a new policy era of American Indian self-determination intended to protect their property and improve their lives.

US President Richard Nixon signs a bill in 1970 to the Taos Pueblo people the title to 48,000 acres of land in New Mexico, watched by an interpreter and tribal leader Juan de Jesus Romero. Credit: Getty Images

In 1974, a court ruling known as the Boldt decision (after Judge George Boldt) interpreted 10 treaties as giving more than a dozen tribes rights to half of the salmon caught in areas of Washington state. Some tribes have generated huge wealth. The Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma has casinos and hotels that contribute to an annual budget of more than $US4 billion ($6 billion), which it uses for hospitals, courts and a police force. Others have seen more mixed fortunes, says Miller, a member of the Eastern Shawnee tribe. “We don’t even have a recognised reservation. So we do not have a land base to engage in economic activities. We have two casinos that make a lot of money. We built a shooting range. But a few years ago, we bought a tyre company, it went bankrupt. We used to own a cabinet shop. That business went under.”

‘They have a very strong set of leadership that keeps bringing the treaty to everyone’s attention … and really just living it so that it doesn’t just get confined to history.’

UN expert Sheryl Lightfoot on Treaty No. 6

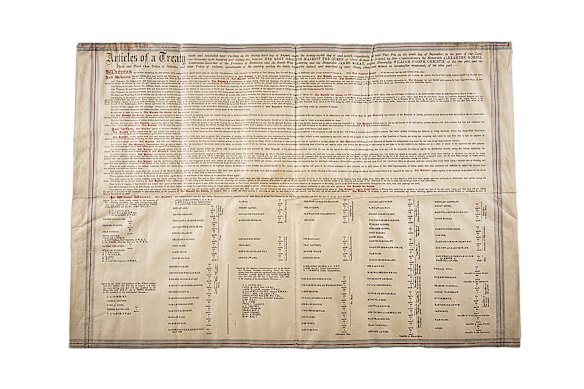

Canada, on the other hand, has both historic and modern treaties. After the British prevailed in a war against France in North America, it issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 to establish rules for relations with Indigenous people that became the basis of treaty-making in Canada. The first treaties were the Upper Canada Land Surrenders (1781 to 1862), which were with First Nations in what is today southern Ontario and which, as the name suggests, involved land being handed over for one-time payments.

Later treaties, known as Canada’s Numbered Treaties (1 to 11, signed between 1871 and 1921), covered most of western and northern Canada and included annual payments, promises for reserve lands and hunting and fishing rights. Today, Treaty 6, which covers 50 nations, is one of the most robust. It includes a provision for a “medicine chest” that has been interpreted as an obligation to provide all forms of healthcare. “They have a very strong set of leadership that keeps bringing the treaty to everyone’s attention, and just clearly articulating it and its understandings and what the obligations of each party are; and really just living it so that it doesn’t just get confined to history,” Sheryl Lightfoot tells us from Toronto.

A copy of one of Canada’s “Numbered Treaties”, No. 6, signed near Carlton and Fort Pitt in Saskatchewan, Canada, in 1876, by officers of the Crown and “the Plain and Wood Cree Tribes of Indians, and other tribes of Indians, inhabitants of the country, within the limits hereafter defined and described by their Chiefs”.Credit: University of Alberta Libraries

Still, treaty-making began to vanish as the Canadian government expanded west from the mid-19th century. “They just threw that out and just started taking more land when Canada moved into the sub Arctic, and the Arctic and British Columbia. So the northern and western edges of the continent, they just did it without the treaty book,” says Lightfoot. “When British Columbia was brought into Canada again [in 1871], it was just done without feeling the need for resolving that situation. And it wasn’t until the courts really forced it, with this evolving body of jurisprudence, that BC as a province and the federal government came to the table and designed the treaties. So it was done by force.”

Leaders of the Nisga’a nation of British Columbia eye a traditional 11-metre-high memorial pole at the National Museum of Scotland which was returned to them in 2023.Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

In 1973, the Canadian Supreme Court decided that Indigenous title existed in modern law, opening the way for the first modern treaty to be signed two years later. The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement led to the Cree and Inuit nations receiving some $250 million in compensation. Today, there are 25 modern treaties in Canada including the Nisga’a Treaty, which recognises 2000 square kilometres of British Columbia as belonging to the Nisga’a nation. They own the land under the legal status “fee simple”, the highest form of private land ownership in common law, which gives them more governing autonomy than they otherwise would have under Canada’s Indian Act.

This comes with its own trade-offs, says Lightfoot. “Under the Indian Act, those governments are reporting up through the Canadian system so that they are not fully autonomous,” she says. “But [entering a treaty] means it has also removed the land protection from trust status under the Crown. So there is some controversy among some of the Indigenous First Nations in BC around whether that is the appropriate application.”

Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan, second left, holds treaty legislation with First Peoples’ Assembly members including co-chairs Ngarra Murray, left, and Rueben Berg in September. Credit: Justin McManus, digitally treated

How does Victoria’s treaty compare?

After a process that began in 2016, Victoria’s Statewide Treaty Bill, due to be debated in parliament this coming week, recognises First Nations people’s unique status as descendants of Australia’s first people; their spiritual, social, cultural and economic relationship with their traditional lands and waters within Victoria; and that they have made a “unique and irreplaceable contribution to the identity and wellbeing of Victoria”.

“First Peoples and Traditional Owners of Country in Victoria maintain that their sovereignty has never been ceded,” the legislation reads. “The historic wrongs and ongoing injustice of colonisation have resulted in unacceptable levels of discrimination, disadvantage and intergenerational trauma for First People.” It also acknowledges First Nations have fought for and won back “some of the rights and status they hold under Aboriginal Lore and Law”. “These rights have been shaped by First Peoples’ Ancestors and are a foundational pillar in the ongoing journey to self-determination.”

The bill creates a governance body for First Peoples living in Victoria, to be known as Gellung Warl, which includes a representative assembly, a permanent truth-telling body and an accountability commission. The terms of the treaty require the government to consult the new body on legislation directed at Aboriginal people and gives Aboriginal people direct oversight of the government’s performance on Closing the Gap and the right to question ministers and officials and conduct inquiries. It also empowers First Peoples representatives to make decisions on certain matters, including developing guidelines for sharing water rights, processes to confirm Aboriginal identity, sanctioning the use of traditional names, and some Aboriginal appointments to government-funded boards. Before debate begins on the bill this week, First Peoples’ Assembly co-chairs Ngarra Murray and Rueben Berg will address the legislative assembly from the floor of parliament.

‘All of the preliminary steps have been geared towards building community understanding … allowing First Nations to lead the process and working slowly in stages.’

Harry Hobbs, associate professor of constitutional law at UNSW

Charles Sturt University’s Dominic O’Sullivan says: “I think what the Victorian treaty is trying to do is give First Peoples a substantive and distinctive voice in government. It isn’t a part of government but it is certainly an influence on government.”

Sheryl Lightfoot says the success of a treaty should be measured by whether it’s meeting the needs of all parties: the government, Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people – “that would be my litmus test”.

UNSW constitutional lawyer Megan Davis agrees: “In my view, treaties or agreements grow from the unique circumstances and conditions of a particular country or state. It’s those conditions that shape what that looks like. So I don’t think any state or territory in Australia could really replicate what’s happened in Victoria because of the unique conditions of Victorian politics.”

Treaty proposals are in various stages in other states, some gaining momentum and others being wound back. Talks have stalled in South Australia, where the government has indicated they could restart after the election next year. In Queensland, the LNP government last year repealed Labor’s 2023 legislation that was intended to work on a treaty negotiation framework.

The Country Liberal Party also dismantled the Northern Territory’s treaty process after it was elected last year. Western Australia has not committed to a treaty process (some legal theorists argue the 2021 WA South West Native Title Settlement, or Noongar settlement, was the nation’s first treaty.)

In NSW, the Aboriginal-led Treaty Commission is in the midst of a 12-month consultation process with First Nations people across the state about whether they want a treaty or any other type of formal agreement-making process and, if so, what it should look like. “Communities are sharing their visions for the future, what a fair and inclusive process looks like, how cultural authority and governance should be realised, and the values that should guide any future treaty or agreement-making,” says the commissioner’s Aden Ridgeway.

Loading

As well as looking to places such as New Zealand and Canada, Ridgeway says some solutions may come from other cultural groups too. “In Scotland, dialogue on treaty-like arrangements has focused on partnership models that acknowledge historical injustice and strengthen Indigenous – Gaelic and Highland – cultural and linguistic revival as part of national identity and policy reform,” he tells us. “While not a formal treaty process, it offers important lessons in cultural renewal, and the value of state-recognised frameworks for self-determination and cultural authority.”

How has Victoria forged its pathway? Says Hobbs: “The Victorian process is really one of the best I’ve seen. All of the preliminary steps have been geared towards building community understanding, building community support, allowing First Nations to lead the process and working slowly in stages. I guess they’re kind of the key factors when you think about modern treaty-making. I’d say the process is more important than the terms.”

This Explainer was brought to you by The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald Explainer team: editor Felicity Lewis and reporters Jackson Graham and Angus Holland. For fascinating insights into the world’s most perplexing topics, sign up for our weekly Explainer newsletter. And read more of our Explainers here.

Explainer team Felicity Lewis, Jackson Graham and Angus Holland.Credit: Simon Schluter

Read the full article here