From the vast Wimmera crop fields of western Victoria, the ancient stone formations of Dyurrite soar sharply above the flat surrounding landscape.

Exquisite rock layers dazzle when the golden sun brings out their orange and grey hues. This place, also known as Mount Arapiles, holds deep spiritual significance for Indigenous people.

The dramatic Dyurrite Cultural Landscape. Credit: Justin McManus

Before European arrival, Dyurrite provided numerous quarry sites Indigenous people used to fashion stone tools. Over recent decades, Dyurrite has become immensely popular with rock climbers, who flock there to test skill and strength in the multitude of climbing routes.

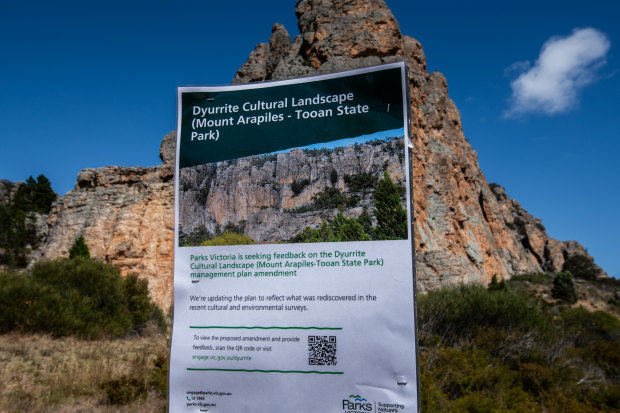

Now, tensions are simmering over access to some sections of the site.

The Barengi Gadjin Land Council and the state government are moving to curb access to some parts of Dyurrite to protect cultural heritage, including quarry complexes, rock art, artefact scatters and scar trees.

The looming restrictions incensed some climbers who argue they have been shut out of the process determining which sections will be closed. They fear the changes will end the region’s reputation as a premier climbing destination.

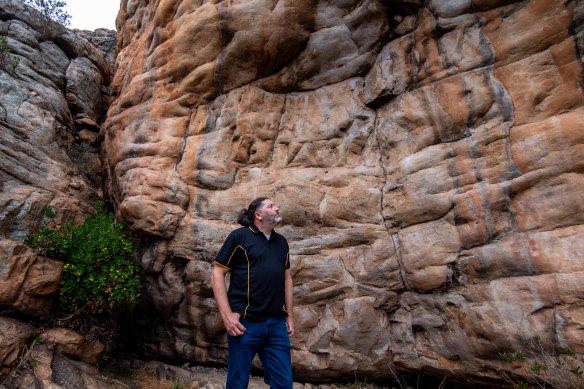

Barengi Gadjin Land Council’s Stuart Harradine. Credit: Justin McManus

However, Stuart Harradine, Barengi Gadjin Land Council spirit officer and spokesman, said he wanted to dispel concerns of a widespread climbing ban. He said only one-third of climbing routes would be closed to protect cultural heritage.

Harradine said his group worked with the Gariwerd and Wimmera Reconciliation Network, which includes climbers, to minimise impact on recreational users.

“It’s not the intent of our mob to stop people coming here,” he said. “It’s just really rebalancing the management of the park as a cultural landscape.”

Harradine recalled how, when visiting Dyurrite as a child, he would see a rock art painting that has since faded. He said weather eroded artworks that were exposed to the elements.

But at one section, Harradine pointed out a faint ochre emu footprint motif with an “m” like figure scratched over it.

Stuart Harradine. Credit: Justin McManus

There are other markings scratched into the walls nearby. Harradine does not suggest climbers deliberately damaged the artwork, but climbing had been undertaken there previously and there are still climbing bolts in the rock surrounding the painting.

He said some artworks were invisible to the naked eye, having been detected through archaeological surveys. The locations of some artworks remain confidential to prevent potential vandalism.

“The majority of climbers would be respectful of cultural heritage and avoid it,” Harradine said. “But it’s not just about the tangible heritage of what people can see and touch. It’s about the intangible, which includes our creation stories and what has happened at particular locations in the landscape which means they are sensitive sites.”

Digital technology is being used to rediscover rock art. Credit: Justin McManus

Harradine said if climbers stayed in identified climbing areas there was no risk of unintended disturbance to cultural heritage.

He said it was important rock paintings were protected, regardless of condition, so they could be potentially restored.

An interim protection order was issued at Dyurrite several years ago to protect Aboriginal heritage. But those areas have since been expanded significantly.

Rock climbers learned of the latest changes when the state government issued a press release about a draft management plan on Melbourne Cup eve.

Dyurrite is immensely popular with rock climbers. Credit: Justin McManus

All climbers The Age spoke to insisted they took great care to avoid disturbing Indigenous sites.

There are some bolts fixed to the rocks at Dyurrite. But long-time rock climber and magazine editor Ross Taylor said most climbers at Dyurrite used “natural protection” safety equipment that does not damage rock and is removed after climbing.

“We have a history of managing ourselves in a very responsible way,” he said.

Climbing legend Louise Shepherd starting climbing at Dyurrite in 1978 and lives in the nearby town of Natimuk. She said Dyurrite was renowned for its variety of climbing routes.

The bans mostly affected the beginner and intermediate routes, she said, as well as some of the hardest ones.

“What makes it stand out is for beginners and intermediate people it’s way better than any other cliff in the world,” Shepherd said. “They’re now taking out massive swathes of the best climbing routes.”

Climbing legend Louise Shepherd. Credit: Justin McManus

Some estimates suggest Dyurrite offers more than 2000 climbing routes. But finding consensus on exactly how many will be affected is all but impossible.

Shepherd has guided thousands of student groups at Dyurrite, and insisted climbing can co-exist with Indigenous cultural preservation. She lashed Parks Victoria’s management plan, accusing it of failing to consult properly with climbers and Wimmera residents.

Parks Victoria’s management plan for the Dyurrite Cultural Landscape reported visitation was increasing by about 3 per cent annually and surpassed 50,000 visitor days per year.

Shepherd feared the bans would erode visitation and gut the economy of Natimuk, where she works part-time in a shop.

Change is coming to Dyurrite. Credit: Justin McManus

She said restrictions risked hampering the region’s ability to attract professionals, including healthcare workers and teachers who are drawn there to climb.

Jack Jane quit working as a full-time climbing guide recently, anticipating the bans, and now works in emergency services.

He said many climbers developed a strong connection to Dyurrite after spending long periods there.

He has climbed at Dyurrite for 20 years and said many climbers were well aware of Indigenous sites, including quarries.

Jack Jane at Dyurrite. Credit: Justin McManus

Jane said it was a pity he could no longer expose young people to the site’s Indigenous heritage while ensuring it remained undisturbed. “I think that’s a loss,” he said.

The state government is seeking feedback on its plan over the coming fortnight.

This week, Environment and Tourism Minister Steve Dimopoulos said it offered an opportunity to bring park users and traditional owners together. “This is an opportunity for us to do something very special there,” he said.

Get to the heart of what’s happening with climate change and the environment. Sign up for our fortnightly Environment newsletter.

Read the full article here