Since the first Winnie-the-Pooh book was published in 1926, the tales of a honey-loving bear and his animal friends have sold more than 50 million copies worldwide.

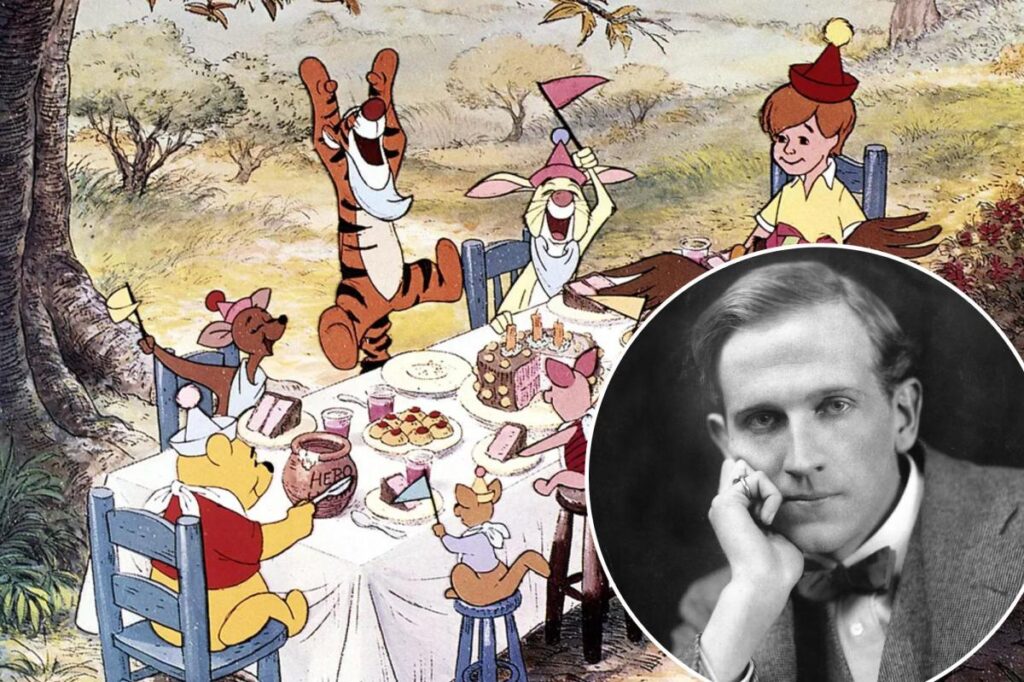

But, as Gyles Brandreth writes in “Somewhere, a Boy and a Bear: A. A. Milne and the Creation of ‘Winnie- the-Pooh’ ” (St. Martin’s Press), behind the children’s books was a complicated adult whose life was fraught with disappointment and regret.

As has been well-documented, Alan Alexander Milne created Winnie-the-Pooh to amuse his young son, Christopher Robin.

An only child, the boy received a stuffed bear for his first birthday. The family named him Winnie-the-Pooh, after Winnipeg, the black bear at London’s Regent’s Park Zoo at the time.

Though largely raised by a live-in nanny, Christopher played with his mother — Dorothy Daphne de Sélincourt, a fun-loving, rich socialite who laughed at husband Milne’s jokes — and she gave his stuffed animals voices and personalities. His father began developing stories about them and they took off.

Initially, the boy loved the attention.

When journalists interviewed Milne, he would often trot “Christopher Robin” out, and Christopher even recorded two albums as his alter ego.

“Even though I was shy, I think I quite liked the attention,” he admitted to Brandreth. But it was also confusing.

“It is difficult to say which came first,” Christopher told the author. “Did I do something and did my father then write a story around it? Or was it the other way about, and did the story come first? . . . But in the end it was all the same: the stories became a part of our lives; we lived them, thought them, spoke them.”

Despite the fact that Milne had created a magical world based on his son’s stuffed animals, the two weren’t that close.

“My father’s heart remained buttoned-up all through his life,” Christopher told Brandreth. “I’m not sure how well I knew him. I’m not sure how well he knew me.”

The son came to resent his father’s fame.

“It seemed to me, almost, that my father had got to where he was by climbing upon my infant shoulders, that he had filched from me my good name and had left me with nothing but the empty fame of being his son,” Christopher wrote in his 1974 memoir, “The Enchanted Places.”

Many who knew him didn’t have the nicest things to say about him.

Ernest Shepard, who illustrated Milne’s children’s books, called him a “rather cagey man.”

Milne played in an amateur cricket team with other celebrity writers J.M. Barrie, H.G. Wells (Milne’s former science teacher), Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Canon Doyle and P.G. Wodehouse.

Wodehouse said Milne had a “curious jealous streak” and that he “never liked him much.”

Milne had falling-outs with his parents and his oldest brother, Barry, with whom he didn’t speak for decades, refusing even to go to his deathbed when called for a reconciliation. When Christopher married his first cousin, Milne disapproved and the two grew further apart.

Milne himself was resentful of Pooh’s success. He’d written sophisticated, adult comedies of manners about marriage and relationships, as well as detective mysteries and psychological portraits of soldiers returning to war, but Pooh overshadowed his adult work, and he felt he was no longer considered a serious playwright or novelist.

World War I also haunted Milne. Though a pacifist, Milne had volunteered for the British Army in 1914, believing that it was the “war to end all wars.” He participated in the Battle of the Somme in France, where 300,000 men were killed. The evening he arrived at the battle zone, he watched an exploding shell blow one of his fellow soldiers “to pieces.”

“It makes me almost physically sick to think of that nightmare of mental and moral degradation, the war,” he later wrote.

After his older brother and best friend Ken died of tuberculosis in 1929, Milne became more closed-off. Both he and his wife embarked on extramarital affairs — she with an American playwright, and he with a young stage actress — though they remained together.

Milne suffered a stroke in 1952 and died in 1956 at age 74. Christopher went to the funeral but never spoke to his mother again.

By the time he met Brandreth in the 1980s, however, he had made peace with Winnie-the-Pooh.

“I now realize that life is too short for regrets,” Christopher said then.

“Our childhood is whatever our childhood was. It’s made us who we are,” he added. “We cannot change it. . . . But we can visit and revisit the best of it whenever we want. And be grateful.”

Read the full article here