Some fields are abandoned, others are being ploughed again by local families in Louvakou, in the Niari department of southwestern Congo. We fly a drone over rain-soaked lands, where until a year ago one of the agricultural projects of Eni Congo, a subsidiary of the Italian oil company Eni, was located.

The project was managed by the Luxembourg-based company Agri Resources, which had a concession of 29,000 hectares of land and experimented with the cultivation of castor oil, intended to supply Eni’s biofuel production in Italy.

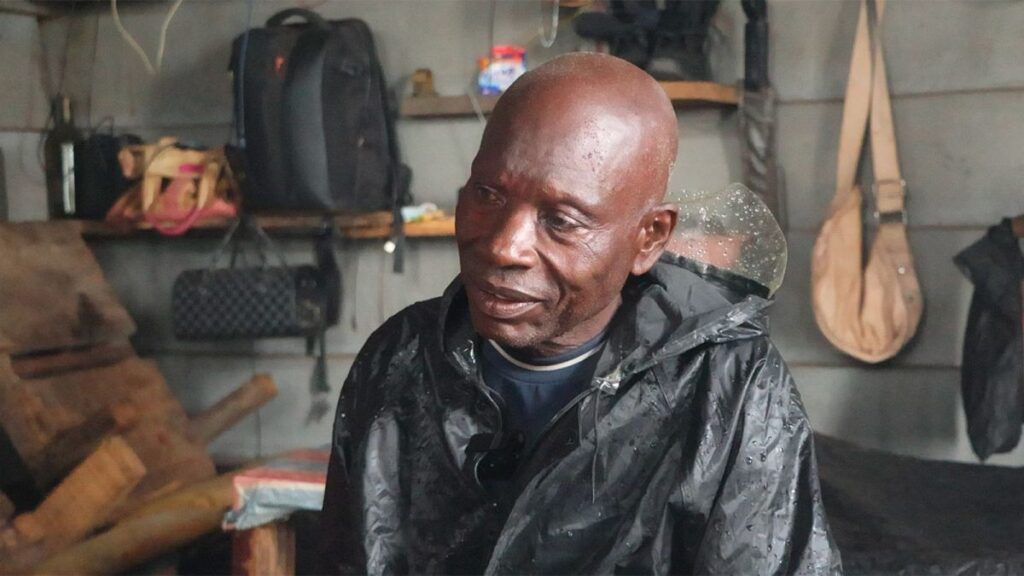

“Agri Resources is not here anymore,” says Joseph Ngoma Koukebene, chief of the nearby Kibindouka village during our visit last November. The chief sits in his yard while telling us that the project has failed, apparently due to poor productivity.

Louvakou is one of three sites in the Republic of Congo where Eni began experimenting in 2022 with the cultivation of castor oil, a non-food crop to be grown “on degraded lands” as a “sustainable agri-feedstock” for biofuels, it said. These are vegetable oils that are not meant to cause deforestation nor compete with food production.

But while these projects are abandoned or still under evaluation, in May this year the company began producing agri-feedstock with other edible crops, such as sunflower and soy, which could have a negative impact on local food security.

What is an Italian oil company doing in Congo?

Eni plans to increase its global bio-refinery capacity from 1.65 million tonnes per year to 5 million tonnes of biofuels and over 2 million tonnes of Sustainable Aviation Fuels by 2030.

To date, Eni mainly produces biofuels using controversial palm oil by-products imported from Indonesia and Malaysia such as PFAD and POME, and Used Cooking Oils.

In order to produce alternative feedstocks and increase production, the company has launched agricultural projects in several countries since 2021, including Congo, Kenya, Mozambique and Ivory Coast.

“To address the availability of feedstock, we have several ongoing projects called agri-hubs, which are focused on producing vegetable oils grown on degraded lands,” Stefano Ballista, director of Enilive, another satellite company of Eni, tells us during a visit in June to a biorefinery in Porto Marghera, Venice.

According to Ballista, the company “aims to produce 700,000 tonnes of vegetable oils” globally by 2028.

In Congo, Eni had originally planned to produce 20,000 tonnes by 2023 from castor oil, brassica and safflower, reaching 250,000 tonnes by 2030. But things went differently: the castor oil project in Louvakou closed its doors, while two others, in the departments of Bouenza and Pool, are still in an experimental phase.

Meanwhile, at the end of May, Eni Congo inaugurated an agri-hub in Loudima, in the Bouenza district.

According to the local press, this pressing plant will produce 30,000 tonnes of vegetable oils destined for bio-refining in 2025, and is supplied by an agricultural production of 1.1 million tonnes of agricultural products such as soy and sunflower, grown on 15,000 hectares.

Degraded land and food security

According to Chris Nsimba, a farmer in Loudima who attended the launch in May, “castor production is still there, but it has been scaled back in favour of other products.”

In 2021 Eni Congo signed an agreement with the Congolese government for the “development of bio-refining agro-feedstock sector,” with a duration of 50 years, involving an area of 150,000 hectares.

The company says its agricultural production in Bouenza will reach 40,000 hectares in 2025.

“We have grown sunflowers, in lands abandoned for decades, with very good yields,” Luigi Ciarrocchi, director of the Agri-Feedstock programme at Eni, told us. According to Ciarrocchi, the use of castor oil in Congo is still “under evaluation.”

Sunflower, like soy or rapeseed, is a food crop. Although Bouenza is called “the breadbasket of Congo” due to its highly fertile grounds, Ciarrocchi claims that Eni is using “degraded lands” that have become less fertile after being abandoned following large-scale agricultural projects in the 1970s and 1980s.

“Our products, which come from this supply chain, are certified at the European level,” Ciarrocchi claims, to ensure that “they meet advanced sustainability criteria, and therefore avoid conflict with the food chain.”

According to the United Nations, in the Republic of Congo “domestic food production meets only 30 per cent of the country’s needs, forcing heavy reliance on food imports.” Meanwhile “chronic malnutrition is a pressing concern, particularly among children under the age of five, of whom 19.6 per cent are affected.”

Ciarrocchi claims that Eni’s agri-hub contributes to the local economy, and has a positive impact on food security through the production of “cakes,” a byproduct of oil production “which has a strong protein component” and will be used as a feed for the local livestock.

Lobbying for biofuels and traditional cars

Europe reduced its support for biofuels in 2022, when the revision of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) discouraged “first-generation” biofuels. These are fuels based on the use of vegetable oils, such as palm oil, which are responsible for deforestation and competition with food security.

EU legislation also bans the sale of internal combustion engine vehicles by 2035, in favour of electric cars, though it recognises a role for “sustainable” biofuels for air transportation.

Eni is part of a coalition which is lobbying the European Commission to recognise traditional vehicles as “zero-emission” through the use of biofuels, claiming that the CO2 produced is the same captured in the atmosphere by crops.

“We have two large manufacturing industries – vehicles and fuel producers – that have come together, united by a single goal,” Emanuela Sardellitti, a senior executive at FuelsEurope told us during an industry event at Eni’s headquarters in Rome in June.

“To prove that even an internal combustion engine vehicle, which is banned by the auto CO2 legislation, therefore by a European standard, starting from 2035, is actually a vehicle that can be qualified as a zero-emission vehicle, through the use of renewable fuels,” she said.

The Italian government backs this campaign in Brussels, and promotes the biofuel feedstock production in Africa through the “Mattei Plan for Africa,” a development plan taking its name from the founder of Eni, Enrico Mattei.

“The Mattei Plan is a vehicle that serves […] for the countries of North Africa and all of Africa to develop agricultural production,” Gilberto Pichetto Fratin, Minister of the Environment and Energy Security of Italy, said at the event at Eni’s headquarters. “And to benefit those countries, but also our country and all of continental Europe, with the consequent production of fuels,” he said.

In Loudima, farmers have an ambivalent opinion of large-scale agricultural projects, such as Eni’s agri-hub.

“Clearly we need everything […] for the development of the Bouenza,” Nsimba told us, “but these are crops that the population does not benefit from, because they are mostly sold on the international market.”

This story was supported bythe Pulitzer Center Rainforest Reporting Grant.

Marien Nzikou-Massala contributed to this report.

Read the full article here