LOS ANGELES — It’s been more than three decades since Yongsik Lee grabbed a shotgun and climbed to the top of his furniture store during the 1992 Los Angeles riots — becoming one of the infamous era’s “Rooftop Koreans.”

After protesters once again squared off with cops on LA’s streets — this time over federal raids targeting migrants — the armed vigilantes who defended the city’s Koreatown are back in vogue.

The “rooftop Koreans” became a viral punchline and meme for anyone who worried LA was descending into violence, and thought Mayor Karen Bass wasn’t doing enough to crack down.

Donald Trump Jr. posted an image to X of an armed man on a roof during the latest rioting in LA along with the caption: “Everybody rioting until the roof starts speaking Korean.”

Lee says the memes sling-shotting around the internet don’t do justice for how scary the times were — and how different the recent round of LA protests and riots are from 1992.

“All of the Korean people, we were just focused on protecting our property. And we were also trying to protect the pride and spirit of our Korean community,” said Lee, who immigrated in 1981 and served in both the Korean and American armed forces.

“We didn’t want to [fight.] We wanted peace,” he said.

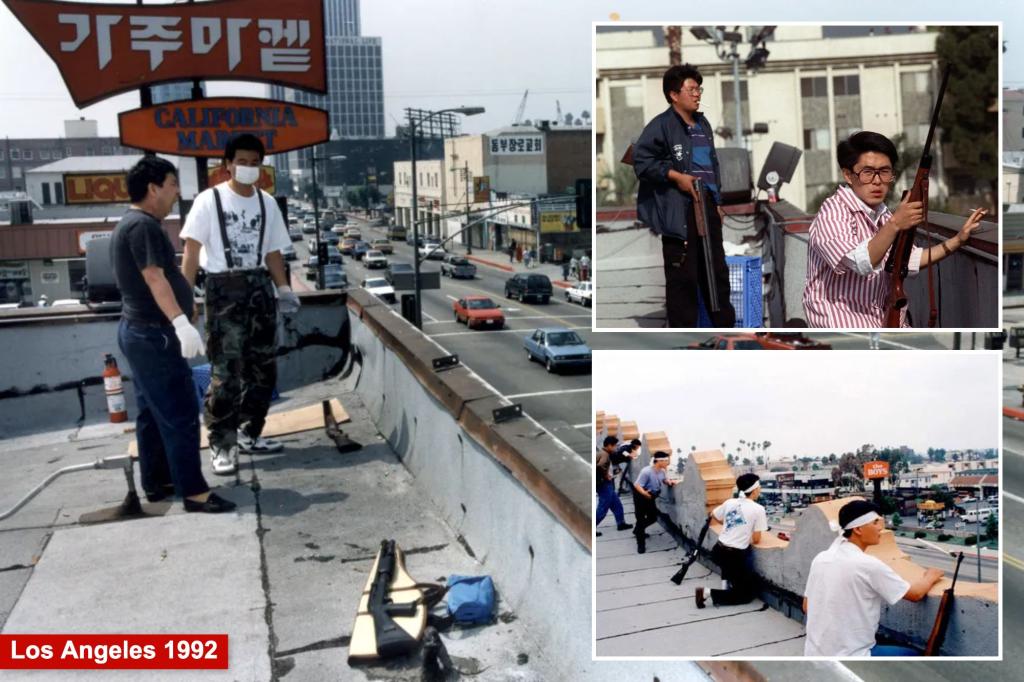

Now-historic photos at the time captured Korean men with rifles perched atop buildings as rioters moved through the city in May 1992.

The mobs looted businesses and set storefronts ablaze after four white police officers were acquitted of the savage beating of Rodney King, a black man. Sixty-three people died, and property damage neared $1 billion in the chaos.

Amid the riots, the police more or less abandoned Koreatown, instead focusing on wealthy, white neighborhoods, Lee said.

“The police were not responsive. They were using Koreatown as a bumper,” Lee said. “I was watching the TV, and I saw things burning down in the south side, and [rioters] were coming up here.”

Lee said that’s when he decided to take matters into his own hands: He picked up his two kids from school, went by Home Depot to buy as many fire extinguishers as he could fit in his car, grabbed a shotgun he had for hunting and joined two neighbors on his roof.

From there, Lee could see other shop owners with guns on nearly every building on his block.

All of them had done mandatory military service back in Korea.

None of them wanted violence, he insisted.

“We didn’t want anybody to get hurt. It was peaceful. We were protecting our property, but we wanted to do it as peacefully as possible,” Lee recalled.

“It wasn’t a matter of protecting my money or my property. It was about my foundation. If I lost those things, I’d lose everything. My whole life in America.”

By the end of the riots, more than 1,800 Korean-owned businesses were still looted or destroyed, according to the Washington Post.

The media would later cast the “Roof Koreans” as allies of law enforcement.

Kyung Hee Lee, who immigrated in the ’80s and saw her tire shop ransacked during the riots, said that narrative is insulting.

“We did what we did because we had no choice,” she said, speaking in Korean.

“We were desperate to survive because the police were not helping the Korean community. The police abandoned the Korean community so the protesters would have something to destroy,” she said.

Many Korean-Americans are supportive of the anti-ICE protests that overtook LA — though they disagree with the rioters.

When Don Jr. posted about the rooftop Koreans, the Korean American Freedom Federation swiftly condemned him, saying the meme “demonstrated poor judgment by mocking the current situation and invoking painful memories,” in a statement to the Korea Times.

Wonil Kim, who was toiling as a construction worker during the 1992 riots, said, “What’s being posted online brings up really painful memories.”

“We are proud of the people who were protecting our community, but those days were really brutal and cruel,” he said.

And things are different now: Koreatown still doesn’t get enough cops, residents say. But in 1992, the Korean community was a poor, fledgling minority; it has since grown and thrived.

“Nowadays nobody will go to the rooftops because we have insurance,” Kim said jokingly.

But at least one “Rooftop Korean” has embraced his legend.

Tony Moon was 19 when he says he grabbed a gun and joined his dad on the roof in 1992.

He has since become a right-wing, Second Amendment advocate, dubbing himself an “OG Roof Korean” on social media.

After the latest protests broke out, he re-posted a meme showing his face shining over Gotham City in place of the Bat Signal, and he has blasted California Gov. Gavin Newsom and LA Mayor Karen Bass for their handling of the crisis.

As for Yongsik Lee, he said he is on the side of the protesters, whom he sees as mostly peaceful, at least when compared to the chaos of the Rodney King riots.

In fact, he finds common ground between the Koreans of the ’90s and present-day Latino migrants, both of whom he sees as scapegoats for the party in power.

But he acknowledged that after three decades, the “Rooftop Koreans’ ” place in the history of Los Angeles depends on who you ask.

“There’s a lot of different Koreans,” Lee said. “When you’re up on the roof, every Korean thinks differently.”

Read the full article here