People affected by Huntington’s disease could at last benefit from the first treatment to slow the fatal neurodegenerative condition.

Scientists from University College London (UCL) found patients receiving the treatment in a clinical trial setting experienced 75 percent less progression of the disease, compared to those with the disease not given the drug.

“This is the first treatment of any kind to convincingly demonstrate slowing of progression in Huntington’s disease (as opposed to managing symptoms with medications that don’t slow progression),” professor Ed Wild, consultant neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery at UCLH, told Newsweek.

“AMT-130 [the new treatment] was also the first gene therapy of any kind to be tested in Huntington’s disease.”

Huntington’s disease affects movement, thinking and behavior and is caused by a single genetic mutation. Anyone with a parent who has the condition has a 50/50 chance of inheriting the mutation themselves.

In the U.S., there are around 41,000 symptomatic Americans and more than 200,000 at-risk of inheriting the disease, according to Huntington’s Disease Society of America. Most people start developing symptoms between the ages of 30 to 50, but it can also occur in children and young adults.

“We can slow the course of the disease [as shown in the trial], which is huge for patients and families. We want to get to a vision of a world where Huntington’s disease is no longer something they have hanging over them for their entire lives,” professor of clinical neurology at UCL, Sarah Tabrizi, told Newsweek.

The Treatment

It’s expected that just a single dose of AMT-130 would last for a person’s whole life. The gene therapy permanently introduces new functional DNA into a patient’s cells, consisting of particles of a “harmless, empty virus.”

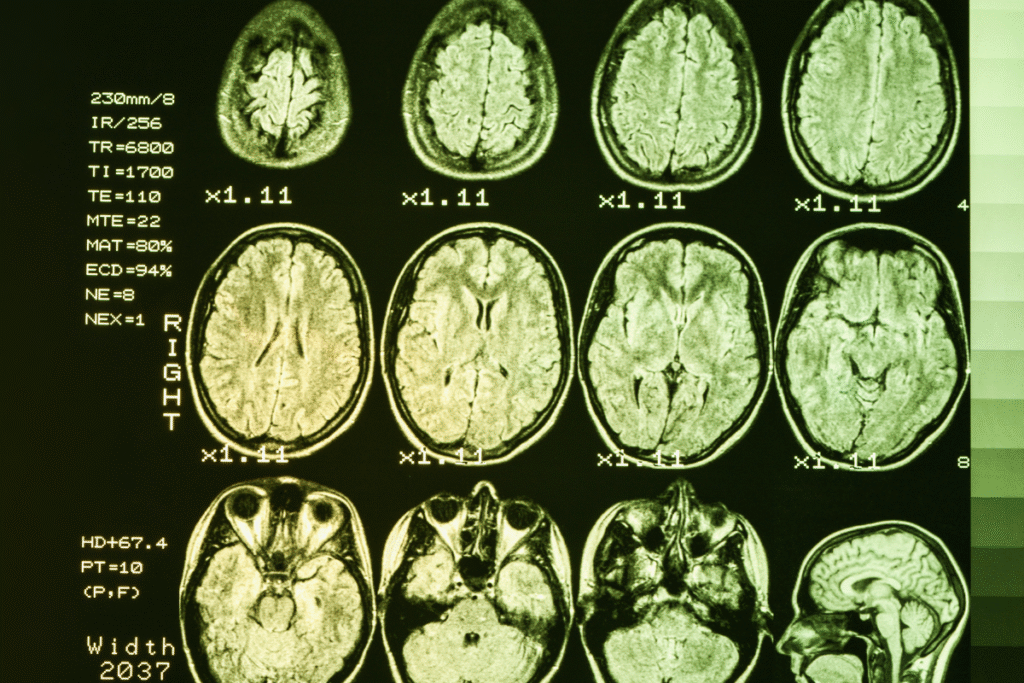

The virus is injected directly into a part of the brain called the striatum in a highly complex form of neurosurgery that takes about 12 to 20 hours. Catheters are guided to the right part of the brain, supported by live MRI images. The virus particles then enter the neurons and release the DNA.

“Basically, the virus turns the nerve cell into a form of a factory that keeps producing—forever—this protein that then switches off the toxic form of the Huntington gene,” Tabrizi explained.

Effectiveness

Results released by drug developer uniQure—with a peer-reviewed publication yet to come—involve 29 patients who completed up to 36 months of the Phase I/II clinical trial, 12 of whom were given a high dose. Their progression was compared to an external cohort of people with Huntington’s disease.

As well as slowing disease progression by 75 percent at 36 months, the scientists found that neurofilament light protein (NfL)—a biomarker of neuronal damage—levels in spinal fluid were lower in people treated with the drug than they had been at the start of the trial.

Typically, NfL levels would be expected to increase by 20–30 percent over three years.

Both Wild and Tabrizi have described the study participants as “brave.”

“All trials of new therapies carry some risk. This was more risky than most because of the need for invasive surgery and the fact that a gene therapy has no ‘off switch’,” Wild explained.

“However, the trial went very smoothly considering the theoretical risk and most complications either settled on their own or with straightforward intervention.

“My patients in the trial are strikingly stable over three years in a way I’m not used to seeing in Huntington’s disease. One of them is my only patient who’s been able to go back to work [after medical retirement].”

What to Expect

Wild explained that when the gene that causes Huntington’s (HTT) was first discovered in 1993, the technology didn’t exist to selectively reduce production of disease-causing programs and a range of therapeutic techniques needed to be developed over time.

Wild added: “To keep things in perspective—it could have taken 20 years longer without ever seeing a success like this.”

In the current trial, patients had mild signs or symptoms of the disease. “But the disease process is essentially the same from birth to death, so lowering the protein before symptoms begin should delay onset as well as progression,” Wild explained.

“If we treat early enough we have every reason to expect additional years or even decades of complete disease-freedom.”

UniQure plans to submit an application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration early next year requesting accelerated approval to market the drug, with applications in the U.K. and Europe to follow, according to the research team.

On whether the drug will be licensed, Wild told us: “In my opinion, yes—but each regulator has its own criteria that need to be satisfied, so it is not inevitable and it will take time.

“Making it available to everyone who needs it is our top priority.”

Tabrizi added the treatment “opens the door to future therapies that can be given to everyone worldwide.”

Do you have a tip on a health story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about Huntington’s disease? Let us know via health@newsweek.com.v

References

uniQure. (2025, September 24). uniQure announces positive topline results from pivotal Phase I/II study of AMT-130 in patients with Huntington’s disease [Press release]. https://uniqure.gcs-web.com/news-releases/news-release-details/uniqure-announces-positive-topline-results-pivotal-phase-iii

Read the full article here