When Jo Kaur, 42, from New York, and her husband Richie, 41, married in 2019, they had no idea that just weeks later they would be expecting their first child.

“It was a honeymoon baby,” Kaur told Newsweek.. The pregnancy went smoothly until late scans suggested their baby was measuring small—possibly a sign of intrauterine growth failure.

Whereas the average newborn weighs about 7.6 pounds in America, Riaan was born weighing just 5 pounds, 6 ounces. At first, doctors reassured the couple. “Everything seemed fine and we were sent home,” Kaur said. But soon, feeding became a challenge. Riaan struggled to latch, vomited often and rarely made eye contact.

“I didn’t realize how unusual that was,” Kaur explains. “I was a first-time mom and had no experience with babies but doctors seemed baffled.”

A Shattering Diagnosis

At three months old, Riaan was referred to an ophthalmologist, where Kaur’s world collapsed. Riaan had cataracts in both eyes.

“I cried, realizing he had never truly seen our faces,” she says. Emergency surgery followed, and genetic testing began.

Initial results offered false reassurance. But at 15-months-old, a comprehensive test revealed the truth: Riaan had cockayne syndrome (CS), a rare and devastating genetic disorder that causes premature aging, growth failure and neurological decline.

His symptoms—including being born very small, not growing properly and having major eye problems—indicated that Riaan has Type II CS, the more severe form.

“The doctor said: ‘It’s not good, I’m sorry,’” Kaur remembers. “We weren’t prepared. It felt like the world dimmed, and we could never restore its color again.”

Some children with CS live into adulthood, but most do not. For Riaan, whose symptoms began so early, the prognosis was severe. Research has shown that for the two most severe forms of CS, life expectancy typically ranges between 5 and 16 years.

Life With Riaan

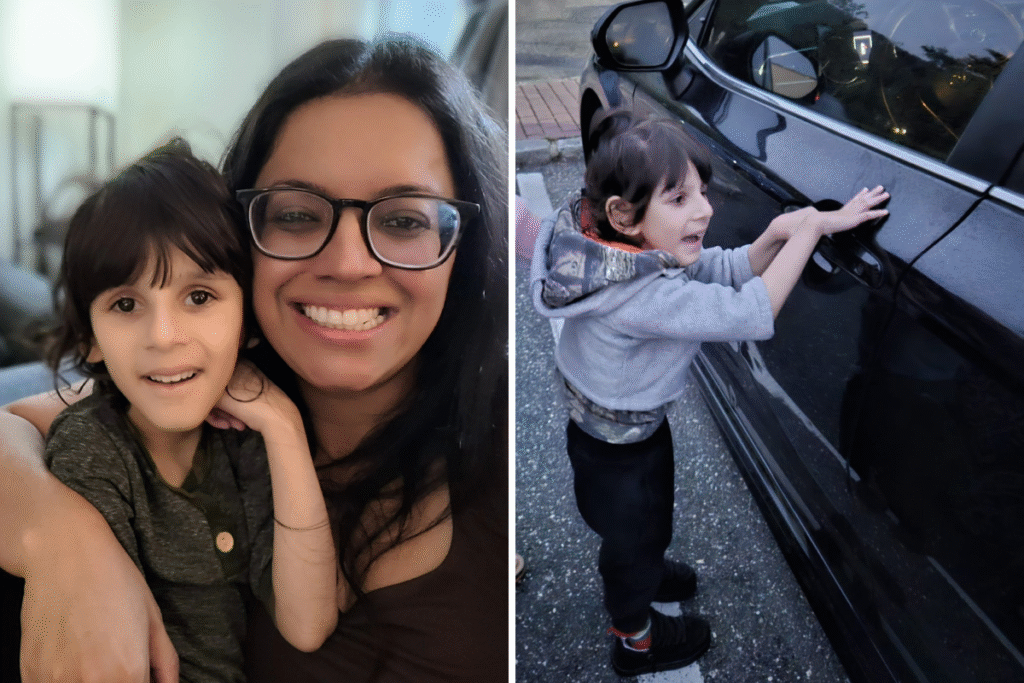

Now five years old, Riaan cannot sit independently or feed himself. He is nonverbal, thin and frail—just 3 feet 4 inches tall and weighing 23 pounds. Yet his presence is full of light.

“He is so social, loving, and happy,” Kaur told Newsweek. “He hugs us, laughs often, and lights up the room. His cognitive and social abilities are striking—sometimes even more advanced than expected.”

The family also welcomed a second son, Jivan, through IVF with genetic testing to ensure he would not inherit CS. Jivan, now three, is taller and heavier than his big brother. The contrast is bittersweet.

“I saw the look in Riaan’s eyes when he noticed Jivan walking while he couldn’t,” Kaur said. “It broke my heart.

“We don’t need Riaan to do everything other children can. All we want is for him to be healthy, happy, and stable. We just want him with us—that’s all we’re trying to do.”

Building Hope Through Research

Immediately after the diagnosis, Kaur began contacting researchers, even writing to the head of the National Institutes of Health. She discovered there was little organized effort to find a treatment.

Three months later, Kaur and her husband founded the Riaan Research Initiative and partnered with UMass Chan Medical School. With researcher Miguel Sena Esteves, they began funding work on a gene therapy that has shown promising results in mice—extending lifespan more than eightfold.

Through tireless storytelling, fundraising and advocacy, they have raised millions of dollars. But the fight isn’t over.

“Clinical trials are heartbreakingly expensive—$350,000 per child,” Kaur said. “Donor fatigue is real and in this economy, it’s hard to keep people’s attention. But every child is worth fighting for.”

A Universal Fight

For Kaur, Riaan’s story is bigger than her family. “This disease can happen to anyone, regardless of education, ethnicity or background,” she said. “

CS is inherited in a recessive way, which means a child must get two faulty copies of the gene—one from each parent—to develop the condition. If a child only gets one faulty copy and one working copy, they won’t usually have symptoms but will be a carrier who can pass the gene on.

When both parents are carriers, each pregnancy has a 25 percent chance of the child being affected, a 50 percent chance of the child being a carrier like the parents, and a 25 percent chance of the child inheriting two working copies and being unaffected. These odds are the same for both boys and girls.

“The issue isn’t finding therapies—it’s funding them,” she said, adding that her mission is to ensure children like Riaan are not forgotten.

She concluded: “We are deeply grateful for the scientists who dedicate themselves to ultra-rare diseases. They care about these children, and so do we.”

Do you have a tip on a health story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about cockayne syndrome? Let us know via health@newsweek.com.

References

Brace, L. E., Vose, S. C., Vargas, D. F., Zhao, S., Wang, X.-P., & Mitchell, J. R. (2013). Lifespan extension by dietary intervention in a mouse model of Cockayne Syndrome uncouples early postnatal development from segmental progeria. Aging Cell, 12(6), 1144–1147. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12142

Hafsi, W., & Saleh, H. M. (2025). Cockayne Syndrome. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525998/

Read the full article here