Rosa Roisinblit was getting ready for her weekly salon appointment when she received the phone call that would alter the course of her life.

“Se llevaron a los chicos,” she heard the distressed voice on the other line say. They took the kids.

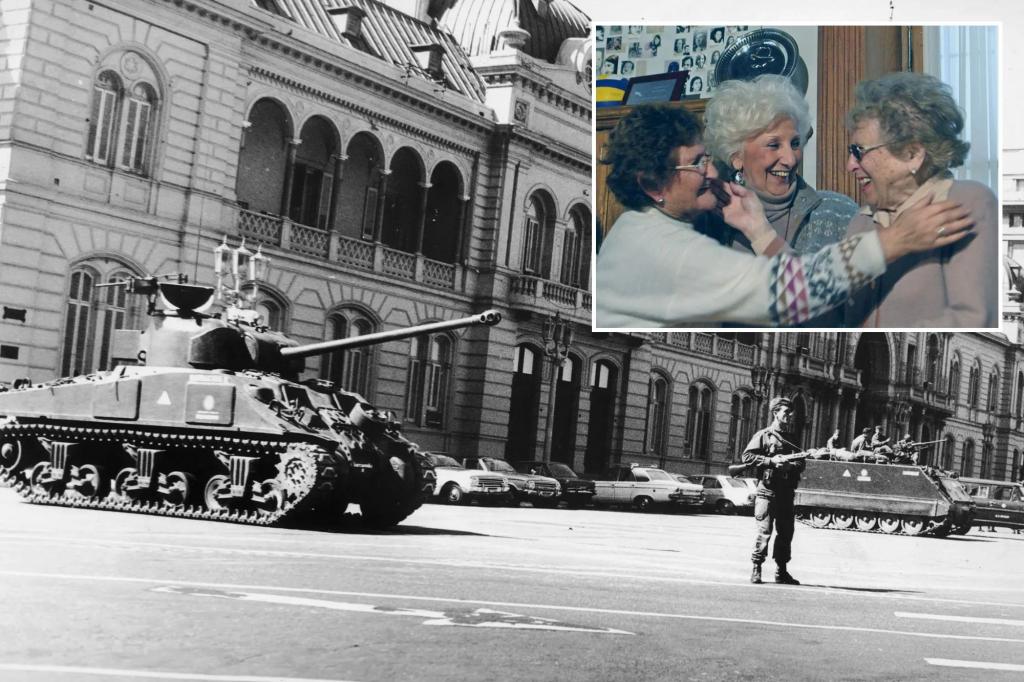

It was a Saturday morning in October 1978, two years after military forces had seized the presidential palace in Buenos Aires and toppled Argentina’s leader, Isabel Peron.

The new government promptly launched a campaign to annihilate the political left, killing thousands.

But Roisinblit didn’t know all the grisly details yet; only that her daughter, Patricia, and son-in-law, José, were in danger.

Patricia and José had once belonged to a group of militant revolutionaries, though they had since abandoned their political activities. José opened a toy shop outside Buenos Aires. The couple had a 15-month-old daughter named Mariana, and Patricia was eight months pregnant with a second child.

Now Patricia was gone, and Roisinblit was desperate to find out what happened to her and her unborn baby. It took her 21 years.

Journalist Haley Cohen Gilliland tells her heart-rending saga in the new book “A Flower Traveled in My Blood: The Incredible True Story of the Grandmothers Who Fought to Find a Stolen Generation of Children” (July 15, Avid Reader Press).

Roisinblit was one of the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, whose grandchildren — many born in captivity — went missing during Argentina’s military junta, from 1976 to 1983.

As Gilliland recounts, these brave women launched mass protests and confronted military officers at a time when speaking out often meant death. They became detectives, donning disguises to spy on their suspected grandchildren. They even teamed up with an American scientist to create groundbreaking genetic tests.

Since the 1970s, they have found 139 grandchildren. The latest was discovered in January of this year.

“The abuelas’ story,” Gilliland told The Post, “demonstrates that persistence matters, that ordinary people can make extraordinary change, and that, ultimately, love triumphs over fear.”

The day before Roisinblit heard that her child went missing, a group of armed men had beat and kidnapped José from his store, then grabbed Patricia and Mariana from their apartment. Later that night, a convoy of cars dumped Mariana with relatives. Patricia screamed as the men wrested her crying child away from her. They then shoved the pregnant mom back into an unmarked car and vanished.

Roisinblit went to a judge. She went to the police. She visited jails and lawyers offices. No one could — or would — give her any information about her family.

Then Roisinblit met the Abuelas.

The abuelas were an offshoot of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, who had drawn attention with their silent marches across the Plaza de Mayo in Central Buenos Aires, wearing white kerchiefs and holding photos of their missing children.

During its reign of terror, the junta abducted hundreds of pregnant women. After giving birth, the mothers were “disappeared” — sometimes drugged and then dropped from airplanes into the sea — and their babies secretly given to other families.

Because of this, the abuelas often didn’t know the names or even the sex of the grandchildren they were searching for.

But, they assured Roisinblit, the more noise they made and the more attention they got, the more likely they would get their children back.

In 1981, two of the abuelas came back from a meeting at the United Nations with a lead. They had met a couple women who had been in the same prison as Patricia. Patricia had given birth to a healthy baby boy.

Throughout the decades, Roisinblit saw many of her fellow abuelas finally meet their missing grandchildren. Sometimes these reunions were sweet — such as the one between her friend Estela and her grandson Ignacio, who shared an instant connection.

But sometimes they were contentious. Some of the children did not want to be separated from the people they considered their parents. They accused the abuelas of claiming grandchildren that weren’t theirs.

In 2000, a caller left a tip at abuelas HQ, saying to look into a man named Guillermo Gómez. He was the spitting image of José. The young man eagerly agreed to take the genetics test that a US scientist had pioneered specifically for the abuelas.

He and Roisinblit were a match.

After Guillermo was born, he had been given to a military man who worked in the prison where Patricia gave birth and where José was tortured. He grew up thinking his parents were his biological parents. And while his adoptive father was violent, Guillermo adored the woman who raised him. He did not want her to go to jail for inadvertently kidnapping him two decades ago.

Roisinblit held firm, and Guillermo eventually took the last names of José and Patricia and joined the board of the abuelas’ organization. He was the one who introduced Gilliland to the 102-year-old Roisinblit, in 2021.

“Sitting in her living room,” recalled Gilliland, “surrounded by smiling black-and-white photos of her disappeared daughter, she told me: ‘I have always told my story exactly as it is. Nothing more. The truth, before everything.’ ”

Read the full article here