But to get to this point, Cook had to upend everything we thought we knew about epilepsy.

Groundbreaking research

Epilepsy is one of the most-common neurological conditions – about one person in every 100 has it.

In the public mind, it is characterised by grand mal seizures – the patient convulses and loses consciousness – but these are just the most-well-known type. A myoclonic seizure causes rapid, uncontrolled limb movement; atonic seizures can cause falls; absence seizures cause the person to lose awareness, as though falling asleep while their eyes remain open.

A decade ago, Cook – director of neurology at St Vincent’s Hospital and founder of Epiminder – was testing an electrode-array manufactured by a US company on patients in Melbourne.

The device required open-brain surgery to read electrical signals off the surface of the brain – a big ask for patients, who knew they were putting themselves at risk of brain injury.

Professor Mark Cook (right) and patient Adam Daly in 2020.Credit: Jason South

Nevertheless, Cook managed to sign up 15 patients. His data, published in Lancet Neurology, showed the device worked well, but few in the field focused on that. Instead, they were agog at Cook’s secondary finding: his patients were having more seizures than they thought. Lots more.

Epileptic patients are usually asked to keep “seizure diaries” tracking the length and frequency of attacks. Doctors use that data to adjust anti-seizure medication doses.

But looking at the direct brain-activity data, Cook saw his patients had almost no idea how many seizures they were really having.

A follow-up study of 3407 patients found 64 per cent of all seizures go unrecorded, and 58 per cent of recorded “seizures” aren’t actually seizures.

“It was really groundbreaking. It was really the first to document really precisely this issue,” said Professor Terence O’Brien, director of neurology at Alfred Health.

This revelation was key for two reasons. First, it suggested doctors might often be getting the dose of medication wrong because the patient wasn’t accurately tracking their seizures. That may explain why treatment does not fully work in 30 to 40 per cent of cases.

Loading

Second, clinical trials for new drugs for epilepsy were also based on the inaccurate seizure-diaries.

And there was an exciting hint at what epilepsy researchers have long viewed as the field’s Holy Grail: seizure forecasting.

If doctors can directly read brain data, they might be able to use AI to elicit patterns in the neural activation that predict an oncoming seizure. The device Cook was testing seemed able to do this for some patients, issuing warnings minutes before an episode.

The data was stunning but asking patients to have electrodes implanted in their brain was too much. Four patients suffered severe side effects, including a build-up of fluid on the brain.

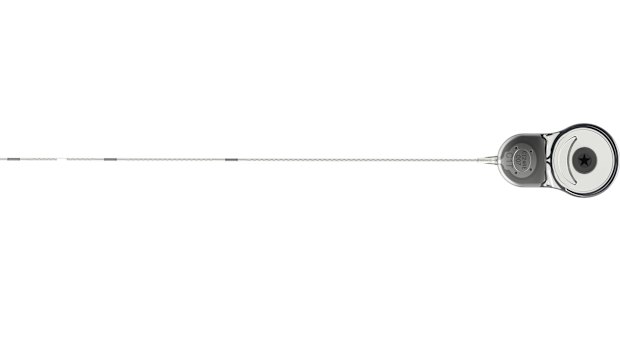

Cook returned to the drawing board, imagining a thin electrode pad that could be slipped beneath the thin skin of the scalp: the Minder.

The electrical patterns it picks up are more diffuse, due to the thick barrier of skull, but “more than accurate enough for what we need”, said Cook.

The Minder can slip beneath the scalp and monitor the brain.

On April 17, US regulators approved the device – based on clinical trial data that is under review at a scientific journal – and it should be available for patients in the second half of the year (several similar devices are under development from other companies and research teams).

“It is a minimally invasive procedure and will not be suitable or appropriate for most patients but there will be some [for whom] it is likely to be very valuable,” said Laureate Professor Sam Berkovic, chief medical officer of the Epilepsy Foundation.

But reading data isn’t enough. Now they need to show it makes a difference.

A study of a single patient wearing the Minder, published in 2021, found it could forecast seizures with a high degree of accuracy (that functionality has not yet been approved by regulators). Now, a large independent taxpayer-funded trial led by Terence O’Brien is trying to work out whether doctors can use the EpiMinder’s data to better-titrate anti-seizure medication.

“It sounds like a no-brainer. But we’re scientists. We do want the evidence to show that,” said O’Brien.

For Scarlett Paige, such a device would have been proof of what was happening to her brain.

Loading

“It will allow people to have more freedom. They’ll be able to go to a neurologist with a pattern,” she said. “It’s having that data to have the evidence.”

Fascinating answers to perplexing questions delivered to your inbox every week. Sign up to get our new Explainer newsletter here.

Read the full article here