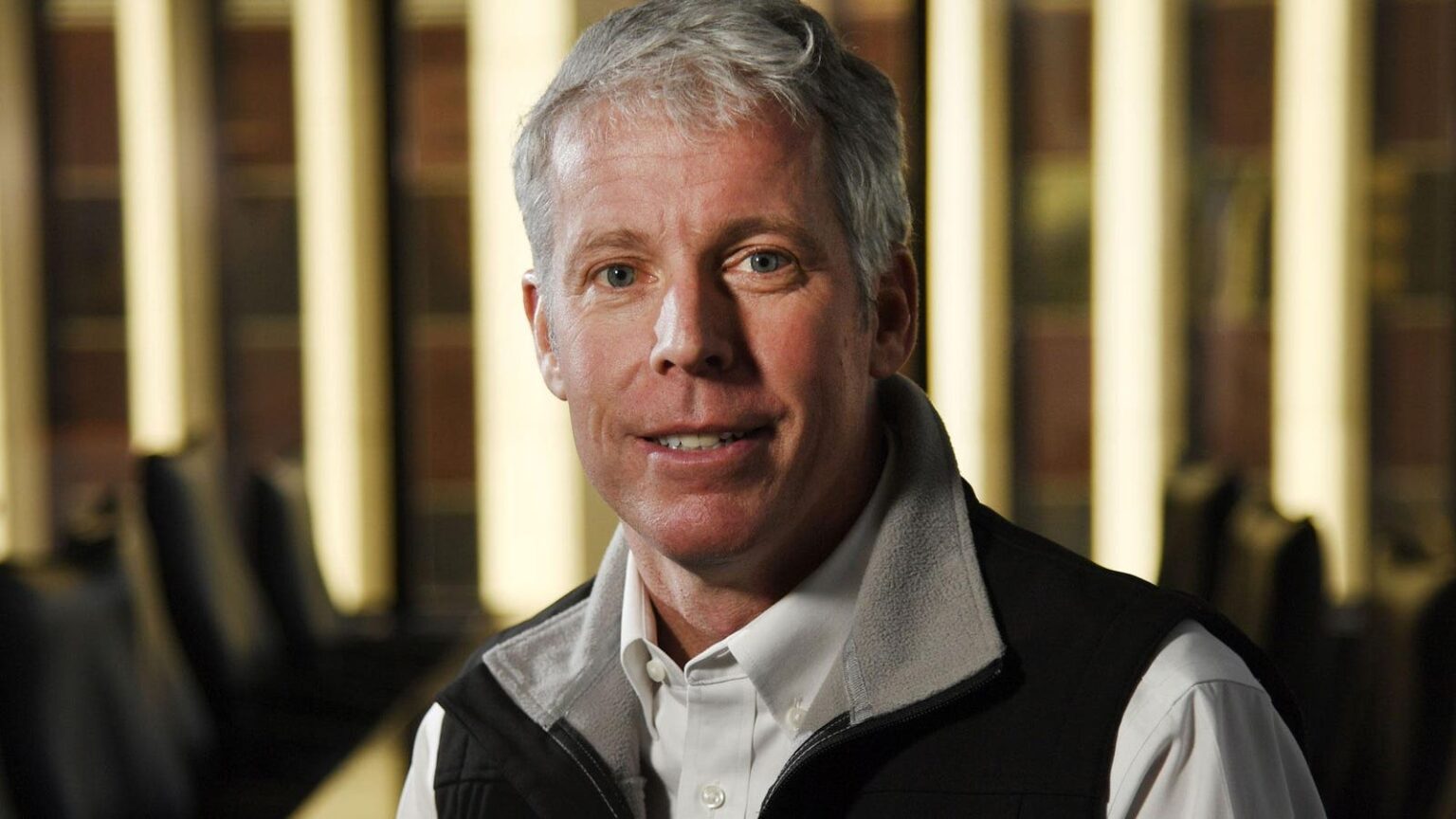

Liberty Energy CEO Wright is an MIT and Berkeley trained engineer running a big fracking company. He’s also an investor in next-gen technology, including Tim Latimer’s Fervo Energy, which aims to frack hot rocks to provide geothermal energy.

By Christopher Helman, Forbes Staff

T

o make the world a better place, you need more reliable, affordable, secure, energy,” Chris Wright, CEO of Liberty Energy, told Forbes, 10 days before President-elect Donald Trump announced he would nominate him as the next secretary of the U.S. Department of Energy. And that’s true, he says, even if the world has to rely on fossil fuels to get there.

Wright, who has been denigrated as a “climate denier,” insists he’s anything but. This self-described nerd with a degree in mechanical engineering from MIT, a masters in electrical engineering from UC Berkeley, and a 30-year track record as a successful entrepreneur, has stated publicly for years his belief that carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas that is no doubt making the atmosphere warmer than it otherwise would be.

Where he diverges from conventional thinking is on what to do about it. To Wright, 59, using less energy is not an option, because humans have proven that we thrive with more. “Any negative impact of climate change has been overwhelmed by the benefits of increasing energy consumption,” he said on a video chat he shared last year. Since World War II, human carbon dioxide emissions have surged. But during that same period, we’ve also enjoyed far less disease, refrigeration, air travel, Wi-Fi, air conditioning – all enabled by fossil fuels, he reasons. “To make the world a better place, to solve the global problems, you need more reliable, affordable, secure energy,” says Wright. “You have to have a successful, wealthy society to do that.”

In the United States, wind and solar energy now generate 16% of total electricity. But Wright is not a fan of those technologies, in part because they require huge land areas and are intermittent–the wind has to blow and the sun has to shine, which means batteries are needed to store their energy for when it’s needed. He doesn’t believe they carry a softer societal and environmental footprint. The batteries are dependent on cobalt mines in Congo, while the solar panels are made with what he describes as “slave labor” polysilicon fabrication plants in China. Wind turbines, for their part, with their steel towers, fiberglass blades and cement bases, are made at plants powered by coal and gas. “All energy production involves trade offs,” he says.

Instead, Wright favors energy sources available 24/7, like natural gas (where he has made his fortune), new types of nuclear power (including nuclear fusion) and geothermal energy. He’s followed through on this belief by investing Liberty’s own capital in startups like Fervo Energy, which is using fracking to liberate geothermal energy from rocks; Oklo, which has a new approach to nuclear fission; sodium-ion battery developer Natron; and Excimer, a nuclear fusion startup.

Wright got into the energy business in 1992 when he founded Pinnacle Technologies, which used “microseismic fracture mapping” to help geologists figure out how oil and gas can flow through cracks and fractures in rock deep underground. He was an advisor to the late Texas billionaire George P. Mitchell, who famously touched off the shale gas boom by figuring out the combo of horizontal drilling plus hydraulic fracturing could unlock previously unfathomable amounts of oil and gas.

To take advantage of the opportunity, Wright and some partners launched their own exploration and production company, Liberty Resources, to acquire 50,000 acres and drill wells in the Bakken fields of North Dakota (where billionaire Harold Hamm had already been drilling), backed by big private equity players Riverstone and Carlyle Group. They found, however, that they couldn’t get reliable fracking services. So they launched their own service company, which over the past decade has become one of the biggest in the entire industry, completing 20% of the wells drilled nationwide.

Liberty now boasts more than $4 billion in annual revenues and is on track for $350 million in net income this year against just $120 million in debt. During the Covid panic in April 2020, when oil dropped to zero, Liberty bought Schlumberger’s North American fracking business in exchange for a 37% equity interest in Liberty worth about $450 million at the time. (Schlumberger has since sold its holdings.) After tanking during the pandemic, Liberty’s share price is about where it was at its 2018 initial public offering; it closed yesterday at $17.72, giving it a market cap of nearly $3 billion. Wright’s current stake in it is worth $50 million.

Although Wright accepts that carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas, he objects to calling it a pollutant, or regulating it as one. “Humans have increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which amplifies the warming and sea level rise since the world came out of the end of the Little Ice Age,” he conceded in a video last year. “The globe is slowly warming and sea levels are gradually rising, and have been for about 100 years.”

The Denver resident and outdoor enthusiast is a big supporter of the Clean Air Act of 1970 and believes it is entirely correct to consider nitrous oxide, mercury, lead, sulfur dioxide, ground level ozone and carbon monoxide as pollutants. He praises sensible regulation of those for reducing bad emissions by 80%.

Liberty’s primary work involves firing up generators with thousands of horsepower to run compressors and pumps that inject millions of gallons of water mixed with sand two miles deep into the Earth, where it blasts open fractures in rock, enabling oil and gas to escape. In the past that was exclusively done with diesel-powered engines. But diesel puts out carbon monoxide and particulates, which Wright wants to get out of the air. So wherever possible, Liberty runs its equipment on clean-burning natural gas. For a month-long pad-drilling completion job, Liberty will haul in and set up a 25 megawatt power plant that runs on natural gas captured directly from the field they’re working on—gas that in the past may have been flared (essentially, burned and wasted) until pipeline hookups were ready.

The fracking business is steady and profitable. In addition to building Liberty Energy, Wright and his team also grew and sold two exploration and production operations in the Bakken, Liberty Resources I & II for about $1.1 billion.

But this energy polymath wasn’t satisfied. So Wright has led Liberty into new territory, investing the company’s capital into several longshot startups that demonstrate his deep interest in scalable, low-carbon energy sources.

Wright says Tim Latimer, the cofounder of geothermal pioneer Fervo Energy, reached out to him in 2016 when he was just starting out and looking for both advice and capital. Latimer had read a paper Wright had written decades earlier after doing a fellowship in Japan to study the feasibility of tapping geothermal energy. “Tim Latimer called me when he was at Stanford because he saw stuff I wrote 30 years ago. My immediate reaction was heck yeah! It clicked.” Wright was psyched that someone was applying fracking tricks to geothermal, fulfilling his dream. But he recognized, “for other investors it was a leap.” So Wright backed Fervo with Liberty’s capital (about $10 million so far) and helped persuade other venture capitalists, telling them “not that it just might work, but is highly likely to work,” he recalls. “I am a believer in the idea and in the team.” (If it works, it would also create a new market for fracking services–Liberty is already providing services to Fervo.)

Also in Liberty’s venture capital portfolio is Oklo, which is developing a small-scale, passively cooled, modular nuclear reactor design utilizing fast neutron technology. It raised $300 million in an IPO this year. Wright approves of Oklo’s plan to build and own its reactors, while selling the power under long-term contracts. Liberty put $10 million into Oklo in 2023, and that investment is now worth about $35 million. Billionaires Sam Altman and Peter Thiel are fellow Oklo backers.

Liberty is also an investor in sodium-ion battery startup Natron, which has raised $19 million from the DOE’s ARPA-E skunkworks program. Liberty’s newest investment is Xcimer, a nuclear fusion startup that last year was selected for a $9 million award from the DOE’s Fusion Development Program.

All these newbies are in line for millions in DOE help and federal investment tax credits, as promised by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)— that is, unless Republicans manage to deep-six the 2022 legislation President Biden and the Democrats pushed through. Trump, for his part, has derided it as a “green new scam.” In our interview, the day after Trump won election, Wright didn’t offer his opinion of the IRA, but insisted he’s not investing in these startups for promised government handouts, but because he believes the technology could be economically viable on its own.

“We want abundant, cheap energy,” Wright declares. Can that desire coexist with future President Trump’s campaign pledges to do away with federal subsidies on all manner of low-carbon power sources? Of course it can, says Wright, and the proof is that companies like Liberty are willing to invest in America’s entrepreneurs. “If you are worried about collecting subsidies for clean energy, maybe you do have reason to be concerned.”

Read the full article here