Watching an American icon like Indiana Jones battle Nazis in “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” it’s hard to believe that it was actually a German cultural institute which played a pivotal role in transforming reckless Jones-style treasure hunting into the modern science of archaeology we know today.

That institute, the German Archaeological Institute at Athens (DAI Athens), has just completed the year-long celebration of its 150th anniversary — just as Greece welcomes record numbers of summer tourists to marvel at the archaeological wonders the institute helped unearth.

Widely regarded as one of the birthplaces of modern archaeological science, the DAI pioneered the transition from indiscriminate digging at archaeological sites to the systematic excavation and meticulous study that continues to inspire researchers and amateur archaeology buffs across the globe.

Until the mid-19th century, archeology was often more about treasure hunting and indiscriminate looting than detailed research and science.

Take Lord Elgin’s controversial removal of sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens, between 1801 and 1812. Although Elgin claimed to have obtained permission from Ottoman authorities — a claim recently refuted by the Turkish government — his sale of the sculptures to the British Museum remains a major cultural and diplomatic dispute between Greece and Britain.

Many view Elgin’s deeds as one of the most notorious colonial-era lootings, alongside famous antiquities brought to museums around the world like the Rosetta Stone.

Even Luigi Palma di Cesnola, the first director of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, was accused of looting classical treasures from Cyprus, where he served as US Consul General in the mid-1860s. Many of the artifacts di Cesnola was said to have plundered were sold, ironically, to the Met itself.

During this period, Greece, newly independent from the Ottoman Empire in 1830, was rich in history but in economic decline owing to decades of war. But it was finally possible for the philhellenists (lovers of Greek culture) to travel to Greece and study its ancient remains. In the later part of the 19th century, Greece’s ancient ruins also became magnets for the era’s great expansionist powers like the United Kingdom and France.

Their ultimate goal? Securing rights to excavate Greece’s most coveted archaeological sites while bolstering diplomatic ties through what we now call “cultural diplomacy.”

Germany was just one of the many countries aspiring to gain excavation rights in Greece. “The oldest foreign archaeological institute in Athens is the French School of Athens, founded in 1846,” explains Katja Sporn, director of the DAI Athens. “But Greece’s allure was such that many countries fought to establish archaeological institutes at the time. Today, there are 20 foreign institutes based in Athens.”

The DAI Athens was founded in 1874, just three years after German unification, during a period of growing German nationalism. Part of the German Archaeological Institute based in Berlin, the DAI Athens’ creation reflected the importance of Greek history to Kaiser Wilhelm I and the close political ties between Germany and Greece, whose first king, Otto, hailed from a Bavarian royal family.

Many Germans at the time saw parallels between Greece’s struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire and their own aspirations for national unification. In the same year the DAI Athens was founded, Sporn explains, the “DAI became subordinate to Germany’s Foreign Office “as a permanent base for internationally active research.”

Today, the DAI Athens is housed in a neoclassical building in downtown Athens where an exhibition for its 150th anniversary showcases its storied history. Among the figures featured is Heinrich Schliemann, an “amateur” archaeologist and businessman who promoted archaeology to a wider public by his emblematic excavations in Troy and Mycenae.

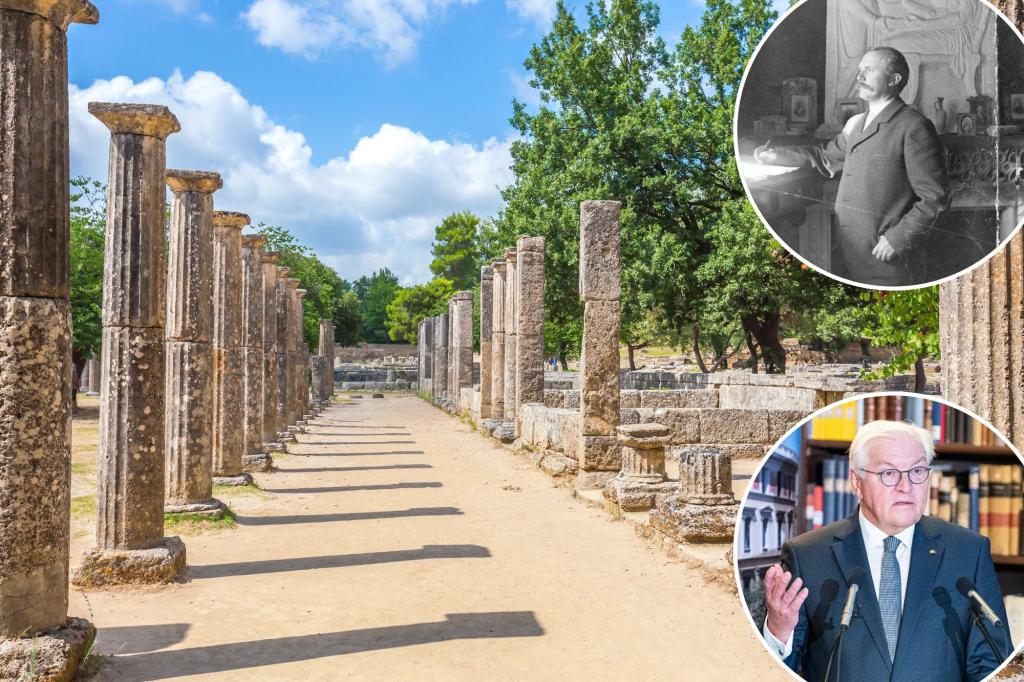

The figure who truly transformed archaeology was the institute’s fourth director, Wilhelm Dörpfeld, who arrived at the DAI Athens in 1887. An architect trained at the excavations in Olympia, Dörpfeld pioneered stratigraphic excavation and both archaeological and architectural documentation methods.

These revolutionized the field by allowing archaeologists to piece together detailed site histories while preserving them for future study. “Dörpfeld’s work was a turning point,” says Sporn. “Archaeologists then worked methodically rather than destructively.”

Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan, the Doreen C. Spritzer Director of Archives at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), agrees. “Dörpfeld’s techniques were taught to archaeologists from Germany, Britain, France and the United States, who then applied and passed them on worldwide,” she says.

This shift — from looting the ancient world to rigorous excavation and research — became the gold standard, paving the way for discoveries such as the tomb of King Tutankhamen by Howard Carter in 1922 and inspiring the swashbuckling tales of Indiana Jones.

Some 150 years ago, in 1875, the German Kaiserreich began excavating the ancient sanctuary of Olympia, the birthplace of the Olympic Games — and the place from which the Olympic torch is now lit 100 days before the start of the modern Olympics every four years.

Olympia wasn’t just another dig; it was governed by a bilateral treaty between Greece and Germany, setting unprecedented levels of oversight for excavation and preservation. Funded by the German government and backed by King George I of Greece, the dig benefited from both financial investment and diplomatic backing.

“Olympia remains one of the most important archaeological sites in Greece,” says Sporn. The excavation uncovered iconic treasures like sculptures from the Temple of Zeus and the statue of Hermes by Praxiteles, but mainly the actual buildings and places where the famous Olympic games were held in antiquity.

Yet the dig — partially overseen by Dörpfeld before he led the DAI — is not only important for what it found, but how it was conducted. An interdisciplinary team, including archaeologists, architects, historians and conservators, ensured a holistic approach to the study of the site and created a global model for archaeological collaborations that remains the gold standard to this day.

Starting from the old excavations in Olympia, the DAI Athens sought to preserve the fragile remnants of Olympia’s past by systematically recording findings and by publishing results in a series of reports. The approach facilitated scholarly research across Europe, shaped future standards for transparency and data-sharing and established archaeology as a rigorous academic discipline.

Crucially, the collaboration with the Greek state ensured that artifacts remained in Greece rather than being shipped off to a museum or private collection abroad, as was common practice at the time. This led to the creation of a dedicated museum at Olympia financed by a Greek patron as early as 1886 — the first on-site museum in the Mediterranean — where the site’s most important finds could be studied and displayed in their original cultural context. Today, museums aligned with excavation sites have become common across the globe.

Ultimately, the dig established “responsible excavation” standards and early conservation techniques that remain in practice to this day.

Back then, Olympia’s success sparked fierce competition among nations vying for other important Greek sites. “A rivalry developed between Germany, France and the United States over the most significant excavations,” says Vogeikoff-Brogan.

They became a battle for prestige among great powers, fueling political alliances between Greece and other countries. For the first time, economic considerations, like trade, would be factored in by Greece to determine who would get the rights to dig the most coveted archaeological sites. Archaeology became an expression not just of Greek national culture — but its newly emerging political might.

The French secured Delphi, aided by trade negotiations involving, of all things, Zante currants, while the Americans started excavations in Corinth and eventually the Agora in Athens, leveraging political alliances and personal relationships. “Social capital and political connections were just as important as archaeological merit in these decisions,” Vogeikoff-Brogan adds.

The positive relationship between the Greek state, its people and the DAI Athens faced a severe setback during WWII. The institute’s ties to Nazi Germany through its director being leader of the German Nazi party in Greece deeply damaged its standing in the country — underscoring the entanglement between DAI Athens and Germany’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“After WWII, it took time for the DAI Athens to regain the trust of the Greek community and reopen,” Sporn explains. The war left lasting scars, and Greeks remained wary of German institutions due to the atrocities committed during the occupation.

Meanwhile, the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) gained prominence in Greece by deliberately distancing itself from politics, establishing itself as another of Greece’s most prominent foreign archaeological and historical education and research institutes.

Today, the DAI Athens has long embraced modernity, digitizing its vast archives for global access and integrating new technologies into its research, particularly in the context of past human-nature relations, ancient land use and climate change. Like all Greek foreign archeological institutions, the DAI works in close collaboration with the Hellenic Ministry of Culture. And by studying how ancient communities adapted to environmental shifts, the institute aims to offer insights into resilience strategies relevant today.

“By examining the past, the DAI Athens continues to research important topics of the present, which may offer perspectives for the future,” Sporn says.

Cheryl Ann Novak is deputy chief editor at BHMA International Edition — Wall Street Journal Publishing Partnership

Read the full article here