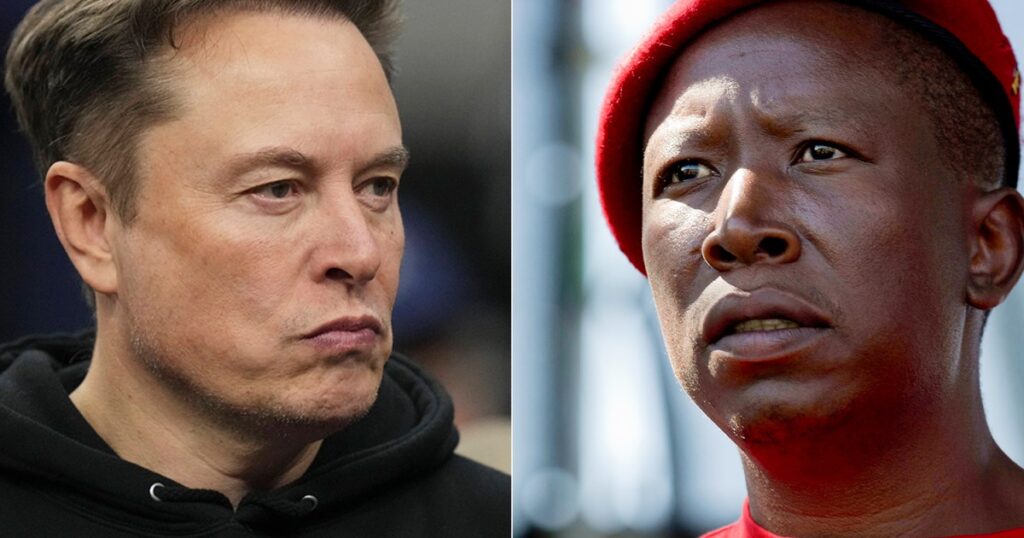

Elon Musk has again waded into South African politics, tweeting on Sunday about “a major political party … that is actively promoting white genocide”.

Sharing a link to a video of Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) leader Julius Malema singing Dubul’ ibhunu (“Kill the Boer”) at a rally on Friday, Musk expressed outrage at “a whole arena chanting about killing white people.”

US President Donald Trump – who counts Musk, the world’s richest man, as a close ally – shared a screenshot of the post on Truth Social. US Secretary of State Marco Rubio penned his own tweet denouncing the song as “a chant that incites violence,” urging the South African government to “protect Afrikaner and other disfavored minorities” and reiterating an invitation to Afrikaners to settle in the US.

But what is this song, and does it have more than one interpretation? Does it constitute hate speech, and who is Julius Malema? And why is the Trump administration so concerned about South Africa?

What is the song all about?

The isiXhosa struggle song Dubul’ ibhunu – the title literally translates to “Kill the Boer” but can also mean “Kill the Afrikaner” – emerged during the 1980s, as opposition to more than three decades of apartheid rule spilled onto the streets of South Africa’s townships. The title of the song is often also translated as “Kill the white farmer”.

Boer is the Afrikaans word for farmer, and on one level, it simply means farmer, of any race. But since the 19th century (when Britain fought two wars against the Boers) it has also meant “Afrikaans person”.

The song’s lyrics essentially repeat the title’s words – “Shoot the Boer” ad infinitum, describing the Boers as “cowards” and “dogs”.

“It was part of the theatre of mass insurrection,” said historian Thula Simpson. “That’s how it is remembered to this day.”

Simpson added that the song is almost always accompanied by toyi-toying – a protest dance that remains synonymous with Black political rallies in South Africa – and is often punctuated by people pretending to shoot Kalashnikov rifles.

Despite being extremely controversial, the song continues to be sung in democratic South Africa, most notably by Malema and by former President Jacob Zuma – his version is quite different – both of whom have left the African National Congress, the party of Nelson Mandela and the liberation movement, to form their own parties.

The ANC, which has ruled South Africa since its first democratic elections in 1994, has seen its support plummet in recent years amid allegations of corruption, misgovernance and broken promises. Last year, it lost its majority for the first time and is now ruling in coalition with a range of parties that have long opposed its policies.

“By singing the song, Malema is trying to present himself as the authentic ANC,” explained Simpson. “It’s all about outflanking the ANC from the left.”

Who is Julius Malema?

Malema shot to prominence in 2008 when, as president of the ANC Youth League, he vehemently defended then-president Zuma who was facing prosecution on corruption charges. “We are prepared to die for Zuma,” Malema famously told a rally. “We are prepared to take up arms and kill for Zuma.”

By 2012 Malema had transformed into Zuma’s biggest critic, and after his expulsion from the ANC, he formed the EFF as a populist, far-left movement.

He first sang Dubul’ ibhunu in 2010, while still ANCYL leader but it has since become something of an EFF calling card. His latest rendition – the one Musk is currently objecting to – came at a rally on Friday commemorating the Sharpeville Massacre on March 21, 1960, in which at least 91 Black people were shot dead by apartheid policemen.

Since 1994, South Africa has marked March 21 as Human Rights Day – “an occasion to recommit ourselves to the advancement of human rights for all,” says President Cyril Ramaphosa. But Malema rejects this, saying that the holiday should be called “Sharpeville Massacre Day” because to give it any other name “undermines the memory of those fallen soldiers who died for our rights as Black people”.

“Whatever your opinion of Malema,” said veteran political commentator Stephen Grootes, “his unique selling point is that he is the loudest voice against anti-Black racism in SA.”

Is the song really a call for white genocide?

Malema has repeatedly stated – both in court and in interviews – that “we are not calling for the slaughter of white people, at least for now”.

And the facts bear this view out: there has never been anything close to an attempted genocide of white South Africans.

Trump and his supporters often claim that white South African farmers are being murdered in their thousands – but statistics provided by AfriForum and the Transvaal Agricultural Union (both groups sympathetic to white farmers) show that about 60 farmers, across all races, are killed every year. This is a country that sees 19,000 murders annually.

Anecdotal evidence points to the same conclusion.

Grootes was one of “about five whites” in the audience the very first time Malema sang the song in public in 2010: “When he sang it, I didn’t notice. It wasn’t in English, and no one around me thought it was a huge event at the time … as a whitey, with an Afrikaans-sounding surname, I did not feel threatened, harassed, scared … I didn’t get the feeling that the people around me were being incited to shoot me.”

Both Malema and AfriForum – the Afrikaner rights group which recently sent a delegation to the Trump White House to seek his support against South African government policies – have used the song as a rallying point for their (diametrically opposed) agendas.

That puts the more moderate ANC in a difficult situation. “Ramaphosa wouldn’t sing the song himself,” said Simpson. “But he hasn’t denounced it either, and his silence means something.”

Can it be legally sung?

Malema has had to defend his decision to sing the song in multiple court cases since 2010. Many of the earlier rulings went against him, finding that the song’s lyrics constituted “hate speech” and were not protected by the right to freedom of speech enshrined in South Africa’s constitution.

More recently, however, the tide has turned in his favour, with the Johannesburg High Court finding in 2022 that AfriForum, which has challenged the right to sing the song, had failed to prove that Malema was inciting harm against “white South Africans of Afrikaner descent” by singing it.

This view was confirmed by the Supreme Court of Appeals in 2024 which ruled that “the reasonably well-informed person would appreciate that when Mr Malema sang Dubula ibhunu … he was not actually calling for farmers, or white South Africans of Afrikaans descent to be shot, nor was he romanticising the violence exacted against them in farm attacks.”

“They would understand that he was using an historic struggle song, with the performance gestures that go with it, as a provocative means of advancing his party’s political agenda,” the court said.

Why do Musk, Trump and Rubio care?

The song is one of several South African political hotcakes – others include the Expropriation Without Compensation Act, and the policy of Black Economic Empowerment – that are inflaming Trump’s MAGA movement. Trump had spoken about the “large-scale killing of farmers” in South Africa in 2018, too.

“Trump and Musk know that if they dangle any of these issues,” said Simpson, “they will get a certain response. South Africa has become a useful foil in America’s domestic culture wars.”

Interestingly, Musk’s and Trump’s response to “Kill the Boer” is more extreme than AfriForum’s.

“When Trump spoke about farmers being murdered in 2018, AfriForum was keen to dissociate itself from the idea that there was a white genocide,” said Simpson. “They are very aware that they are being accused of all sorts of disinformation, so they have to paint within the lines. Trump and Musk, however, have no such limitations.”

For Musk and Trump, though, the equation is simpler, suggested Grootes. “South Africa is the embodiment of DEI [diversity, equity and inclusion],” he said. “Of course, Trump hates us.”

Read the full article here