A known human carcinogen has been found in drinking water sources across the country, according to a report by the environmental organization Waterkeeper Alliance.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, referred to as PFAS or “forever chemicals,” as a Group 1 carcinogen. The Waterkeeper Alliance’s study shows the prevalence of the harmful chemicals in U.S. surface water, a major source of the country’s drinking water.

Newsweek has contacted the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for comment via email.

The Context

PFAS chemicals have been widely used across various industries and consumer products for many years—such as in nonstick cookware, waterproof clothing and stain-resistant furniture. However, more research has been raising caution to the harm the substances pose to public health.

Water contamination in U.S. drinking water systems has also become a growing concern across the country, and the Environmental Working Group’s water contaminant database shows that in many states, certain harmful contaminants are in drinking water at levels higher than the EPA’s maximum contaminant levels.

The Environmental Working Group recently shared a study showing that more than 50,000 lifetime cancer cases in the U.S. could be prevented if drinking water treatment were developed to be able to handle a “multi-contaminant approach, tackling several pollutants at once.”

As contaminants in water systems can pose risks to public health, particularly at levels higher than legally enforced by the EPA—and some even argue that these levels should be lowered—advocacy groups have called for advancing the treatment of drinking water to maximize public safety.

What To Know

Long-term PFAS exposure “can cause cancer and other serious illnesses that decrease quality of life or result in death,” according to an EPA fact sheet on the substances. The agency added that PFAS exposure, which can be via inhalation or ingestion, “during critical life stages such as pregnancy or early childhood can also result in adverse health impacts.”

There are many sources of human PFAS exposure, including through “manufacturing, wastewater treatment, sludge application to land, firefighting foam, building products, personal care products, and dietary sources,” Phil Brown, the director of the Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute at Northeastern University, told Newsweek.

While PFAS are present in many everyday products, humans “get most of their exposure to PFAS from drinking water contamination,” Graham F. Peaslee, a professor of physics at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, told Newsweek.

This is because “there is no economical way to filter out PFAS from drinking water on a large scale,” he added.

PFAS are “forever chemicals” that do not break down naturally in the environment, so when they get into our wastewater, “they pass right through any filters we have back into the landfill leachate and reenter the drinking water and irrigation water time and time again,” Peaslee said.

A result of drinking water tainted with PFAS is chemicals can “build up in different organs,” he added.

So even low concentrations of PFAS in drinking water have been shown to “have toxic effects on cells at concentrations of a part per trillion,” Peaslee continued.

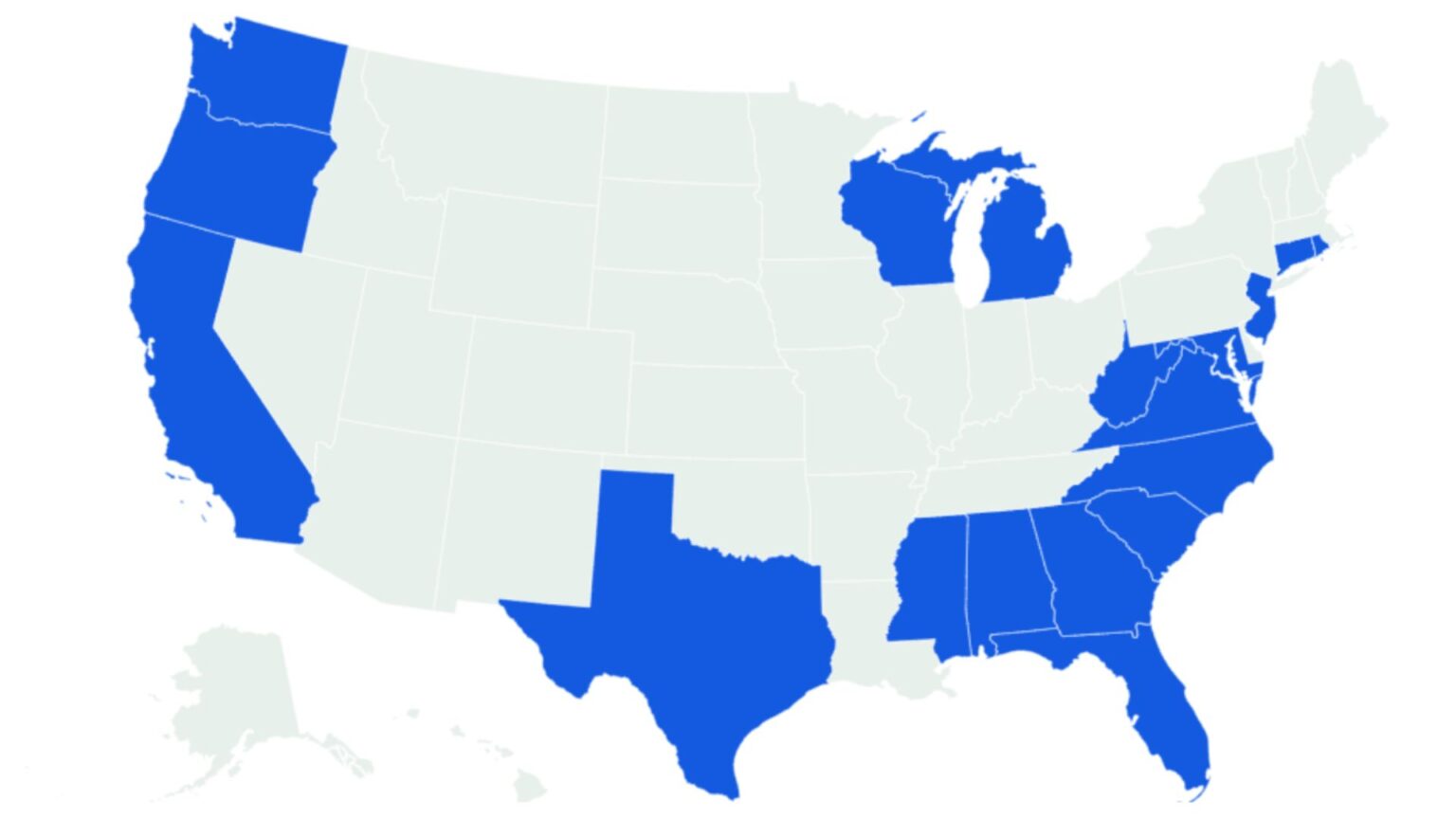

The study, released in June, found that PFAS were present in 83 percent of the waterways tested—with at least one of the substance’s various compounds found in 95 of 114 sites sampled across 34 states and the District of Columbia.

In total, 55 different compounds, out of the thousands of types of PFAS, were analyzed, and 35 were detected in about 63 percent of the sites.

The states with PFAS in drinking water sources included Alabama, California, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia and Wisconsin.

In April 2024, the EPA announced legally enforceable levels for six different compounds of PFAS, including perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), which have maximum contaminant levels of four parts per trillion (ppt) each.

In May, the Trump administration’s EPA said it would continue with the Biden administration’s maximum contaminant level guidelines for only two of these PFAS—PFOA and PFOS—while it rescinded the guidelines for the other compounds.

While the legal limits for these substances have already been established, public water systems have until 2027 to adhere to the monitoring guidelines and provide public information on these levels in their water supply.

By 2029, public water systems must have implemented solutions that ensure the six PFAS levels are within the EPA’s given maximum contaminant levels.

According to the Waterkeeper Alliance’s findings, many of the states tested had levels of PFAS compounds—specifically PFOA and PFOS—significantly higher than the EPA’s maximum contaminant levels.

A South Carolinian waterway had levels of six different PFAS chemicals higher than 20 ppt—with PFOA levels at 28 ppt and PFOS levels at 30 ppt—while a North Carolinian waterway had levels of five different PFAS chemicals higher than or equal to 10 ppt, with PFOA levels at 10 ppt and PFOS levels at 23 ppt.

A Michigan waterway had the highest recorded level for PFOA in the study, at 44 ppt, while the South Carolinian waterway had the highest measure of PFOS at 30 ppt.

When asked about the study, Brown told Newsweek he was “very concerned” about the findings. He said that associations had been found between PFAS exposure and thyroid disease, kidney cancer, high cholesterol, ulcerative colitis, pregnancy-induced hypertension and testicular cancer, as well as many other health conditions.

The Waterkeeper Alliance encompasses more than 300 community-based Waterkeeper groups around the world and advocates for citizen action on issues that affect waterways, such as pollution and climate change.

What People Are Saying

Graham F. Peaslee, a professor of physics at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, told Newsweek: “For a lifetime of exposure at these concentrations in our drinking water, the risk of disease was unacceptably high. What is even more scary is that 98 percent of the PFAS in our drinking water are not even measured by current techniques. And while some of them may not be as toxic, we have yet to find one that doesn’t disturb human or environmental health because of their extreme persistence.”

He added: “I can confirm that in our studies of the environment in several U.S. states, we have seen a majority of surface waters with elevated PFAS concentrations. So this report goes a long way toward identifying how it got into the environment without having a chemical factory nearby producing PFAS—as has occurred in North Carolina, Minnesota, Ohio and New Jersey—nor even an airport using firefighting foams nearby, as has occurred at every military and most civilian airports in the U.S.”

Peaslee said: “The consumer products we use are leaching out their PFAS in our landfills and wastewater and getting back into surface waters. This is one of the reasons why the PFAS contamination that has already occurred is thought to be the most expensive cleanup the U.S. has yet to face.”

Jennifer L. Freeman, a professor of toxicology at Purdue University, Indiana, told Newsweek: “The detection of PFAS in drinking water sources throughout the country is of no surprise given the long history of use in multiple applications. As we collect and analyze more sampling data, we are attaining a more thorough picture of which PFAS are being detected and where their hotspots of higher concentrations are located. With this knowledge, hopefully those sources will be able to be treated to reduce exposures.”

She added: “I advise to reduce your PFAS exposure as much as possible for items consumers can control. For drinking water, this recommendation is different since consumers are attaining their water from public community drinking water entities or their own private well. In hotspot areas, individuals are currently recommended to use filtration sources whether from a public or private drinking water source.”

Freeman said: “Ideally, we need to strengthen drinking water monitoring and treatment to reduce PFAS exposure through this route. The [maximum contaminant levels] set by the EPA in April 2024 are in the right direction. We should not weaken these or roll any of them back as was most recently proposed. Instead, we need to continue to strengthen these MCLs and expand to other PFAS to also reduce their exposure.”

Phil Brown, the director of the Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute at Northeastern University, told Newsweek: “We need continued enforcement of EPA’s maximum contaminant levels, which only came about in 2024. The administration’s anti-regulatory actions, especially at EPA, now put this into question. They have removed four of the six PFAS compounds from regulation and are talking about removing the remaining two.”

He added: “PFAS gets into water from so many sources, so upstream removal is important before it seeps into the surface water and groundwater from which drinking water is derived. Many uses of PFAS can be stopped easily, and some states have passed laws on this. Some large companies have made their own changes to reduce or remove PFAS use.”

Bryan Berger, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Virginia, told Newsweek: “This is concerning in that chronic exposure through bathing, drinking or other forms of direct contact could lead to increased bioaccumulation and toxicity. The sites chosen span major urban areas as well as watersheds, suggesting this is a more significant problem that will persist. It also speaks to the need for enhanced testing methods like we are developing as part of our EPA STAR grant. I’m hopeful ours and others technologies can help provide more rapid, granular testing of water to identify how temperature, rain and other external variables influence PFAS mobility so we can design containment strategies to minimize their spread into our water systems.”

Read the full article here