The idea relies on the fact animals and plants have a makeup of elements specific to where they live.

A fish swimming off the coast of the Northern Territory may have infinitesimally small traces of uranium atoms compared to a fish of the same species caught off Sydney, for example, due to the territory’s history of uranium mining.

The device uses X-ray fluorescence (XRF) scanning technology to send three beams through a fish sample which reveals the exact makeup of elements in its body.

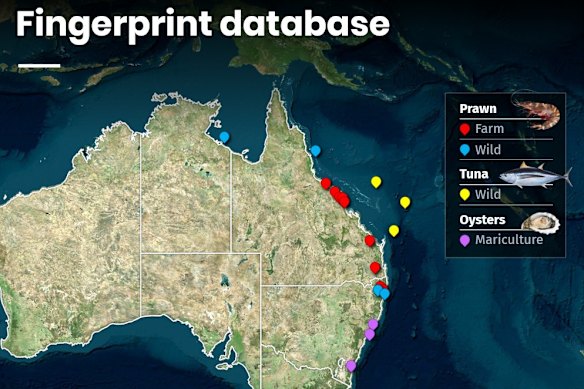

Mazumder and his team have collaborated with fisheries and researchers across Australia and South East Asia to build a database of these “elemental signatures” matched to specific locations.

That means the device can scan a fillet and determine where it came from, and whether the fish was farmed or wild-caught, with over 80 per cent accuracy.

In a demonstration, the ANSTO team analysed two almost identical bream; one from the Clarence River in Yamba, the other from the Hunter River near Newcastle.

The XRF scanner picks up tiny differences in the elemental makeup of fish and other products, allowing scientists to trace their origin.Credit: Steven Siewert

DNA analysis would tell you it’s the same species, but the team’s XRF analysis delves deeper: the bream have different levels of calcium, phosphorous and chlorine. The scan also revealed the Yamba bream has traces of rare-earth metal neodymium, while the Newcastle fish had none.

Now the researchers have the elemental fingerprints of fish from those rivers in the database, future products can be traced back to the Hunter and Clarence.

Early trials of the scanning technique have already uncovered “Australian” tiger prawns on sale for Christmas at a Sydney fish market were actually from Malaysia.

The device has also busted fraudulent sales of Kakadu plum, which undercut authentic Aboriginal producers of the sought-after fruit in the Northern Territory and Western Australia. Almost 90 per cent of overseas products sold as Kakadu plum were bogus.

In one instance, a product sold online as authentic Kakadu plum powder was busted as corn flour.

ANSTO is collecting the specific elemental fingerprints of a range of wild-caught and farmed prawns, tuna, oysters and other seafood for a tool that would allow investigators to prove where products sold in stores and restaurants actually came from.Credit: ANSTO

The US Food & Drug Administration estimates food fraud costs the global economy as much as US$40 billion a year. The ANSTO team have focused their early efforts on seafood because it’s an industry rife with mislabelling and a long and hazy supply chain. While global fish stocks are crashing, knowing where seafood products really came from is critical for sustainability.

From June, new labelling laws will kick in requiring restaurants and cafés to label seafood with its country of origin, a move partly driven by rife mislabelling and the dangers of eating fish of unknown origin. Mazumder’s device presents a way to enforce that requirement.

Loading

The scanner could one day be used by wholesalers to check the authenticity of imported products. Consumers could arm themselves with one to check where the food in their grocery baskets has come from.

“Consumers are really interested to know what is the source and origin of the product, whether it’s farmed or wild-caught,” Mazumder said.

The ANSTO team will present their technology at the World Expo in Osaka, Japan, next week as they recruit for more global collaborators to build their food provenance database.

The Examine newsletter explains and analyses science with a rigorous focus on the evidence. Sign up to get it each week.

Read the full article here