The White House’s method for calculating reciprocal tariffs has left many economists, including those cited by the administration in its formulations, puzzled.

Economists told Newsweek that the methods employed appeared far simpler than the administration has claimed, and that the final “discounted” duties adopted on Wednesday were well above the optimal levels for enhancing American trade.

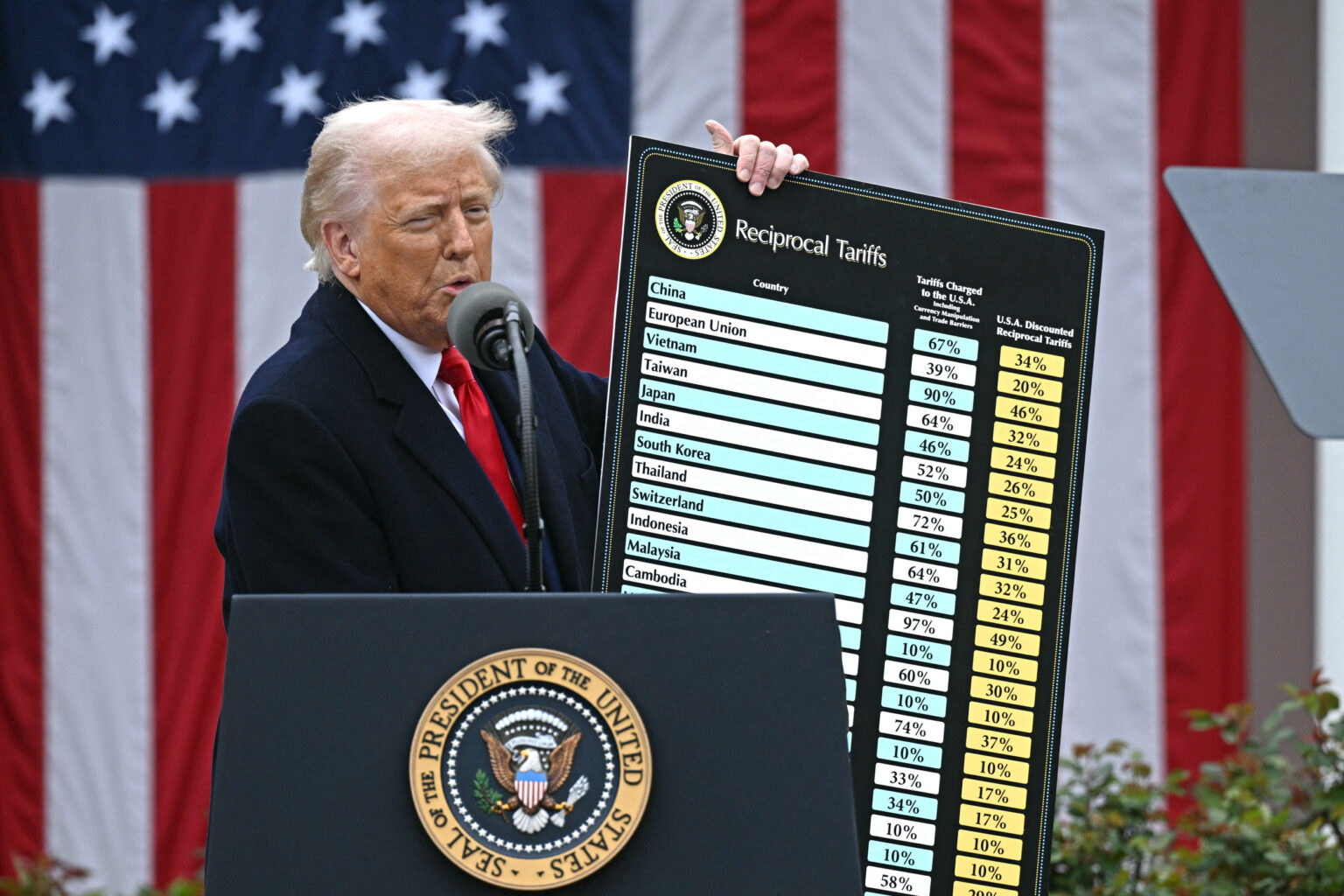

On Wednesday, Trump revealed the rates at which each country’s imports would now be taxed when entering the U.S., rates he described as “very kind” given the level at which the administration said U.S. goods were tariffed abroad.

As economists quickly observed, the rate of tariffs applied to the U.S., which the administration said factors in “currency manipulation and trade barriers,” could be arrived at by simply dividing the a country’s trade surplus with the U.S. by the value of its exports, and then multiplying the number by 100 to express this a percentage.

This was contrary to Trump’s claim that the figure was derived from a calculation of “the combined rate of all their tariffs, nonmonetary barriers and other forms of cheating.”

Further confusion was caused by the resultant “reciprocal tariffs,” which were essentially equal to half of the “tariffs charged to the U.S.A.”

Newsweek reached out to the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) on Thursday via email for comment.

Trade counselor Peter Navarro told CNBC that the calculations were “based on very sophisticated analyses in the trade literature for decades.”

However, Pau Pujolas, professor of economics at McMaster University, said he was “suspicious” about how the administration came up with the figures.

Pujolas’s 2024 paper, Trade Deficits with Trade Wars, was cited by the USTR in its methodology released following Trump’s speech, which included a complex formula involving Greek letters it said was used to calculate the ideal tariff rate for driving bilateral trade deficits to zero.

Pujolas’ paper, co-authored with Jack Rossbach of Georgetown University, Qatar, concerns the relationship between trade deficits and tariffs, attempts to compute “optimal tariff rates” for the U.S. in response to another country’s, and states in its summary that “free trade benefits both countries compared to a trade war.”

“The way in which we calculate the tariffs is using a sophisticated quantitative model that needs to go through a supercomputer to speed up what the tariff rates are,” Pujolas said. “I do not think that that’s what they have done.”

Pujolas told Newsweek that, according to his model, the U.S. should not be tariffing products from the European Union, a bloc on which Trump announced a 20 percent “discounted reciprocal tariff” on Wednesday.

He added that the optimal rates outlined in his paper were “substantially smaller” than the ones unveiled during the Rose Garden speech. “We find that the tariffs should be in the range of 20 percent to 25 percent. Making them higher is a bad idea for the United States,” he said.

“So all things combined, it makes me think that there are some discrepancies between what the administration has done and what our work recommends as optimal.”

However, Pujolas stopped short of claiming that the administration had misinterpreted his paper—one of five academic studies cited by the USTR—noting that he could not be sure which specific points they had drawn from the research.

“They pulled two numbers out of thin air that perfectly canceled each other out,” said Anson Soderbery, an economics professor whose 2018 paper on “trade elasticities” was also referenced in the USTR’s methodology.

Soderbery told The Washington Post that the administration had not outlined the objectives of the new policy, nor had its formula taken account of potential retaliatory measures such as tariffs or boycotts of American products abroad in response to new tariffs.

“They had to come up with numbers that made him look good, and that would make U.S. [trade] look bad,” said Peter Simon, professor of economics at Northeastern University.

Simon told Newsweek that the administration’s figures appeared “made up,” and questioned the rationale underlying Trump’s entire trade agenda, namely that deficits are an economic negative, while surpluses reflect cheating or unfair practices.

“It’s not as bad a situation as he thinks, especially when you’re one of the richest countries in the world,” Simon said. “Many economists claim that running a trade deficit is beneficial because you’re borrowing from them.

“So, no, it’s not the huge anchor around our neck that he claims it to be.”

Read the full article here