“These constructions, metal-organic frameworks, can be used to harvest water from desert air, capture carbon dioxide, store toxic gases or catalyse chemical reactions.”

It was Robson who made the first discovery in 1989, when he combined positively charged copper ions and found they formed an ordered crystal, filled with cavities. Kitagawa and Yaghi built on his work, showing gases could flow through the crystals, and that they were highly stable.

The stable metal organic frameworks can be compared to the timber framework of a house.

These structures can absorb and contain gases inside these frameworks, with many practical applications today, such as capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere or sucking water out of dry desert air.

Olof Ramström, a member of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, described the discovery as similar to Hermione Granger’s enchanted handbag in the fictional Harry Potter series: small on the outside but very large on the inside.

Robson described himself as a classic lone chemist, “an obsessive individual, neglecting other responsibilities”. He said he would have preferred a career in mathematics and felt “second-rate” as a chemist.

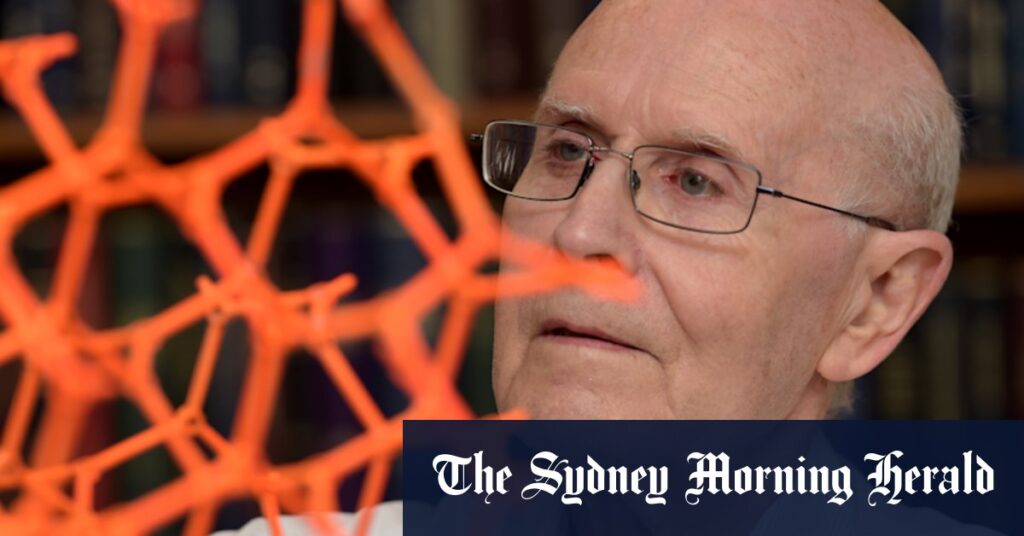

Melbourne professor Richard Robson said he planned to celebrate modestly after winning the Nobel Prize for Chemistry.Credit: Melbourne University

The idea came to him, he told the Nobel organisation, while he was building models of molecules using wooden balls and metal rods. What if he built a structure where organic molecules connected metallic ones?

Robson then sat on the idea for 10 years, always thinking, “I really ought to do something with that”.

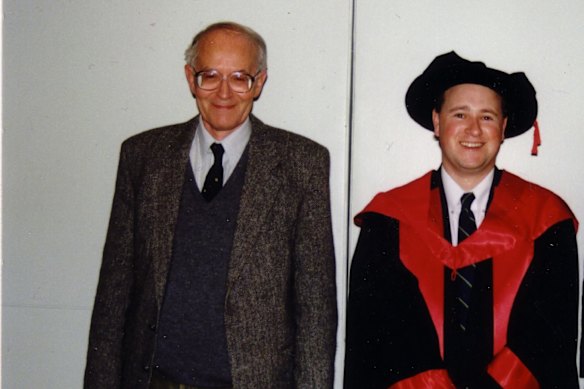

For years, Stuart Batten has eagerly tuned into the Nobel Prize announcements, hoping to see Robson, his former PhD supervisor, recognised for his groundbreaking contributions to the field of chemistry.

On Wednesday night, that long-awaited moment finally arrived.

University of Melbourne PhD student Stuart Batten, right, with his supervisor and now Nobel Prize winner Richard Robson in 1996.

“As soon as they started reading out the names, it got very exciting, very quickly,” Batten said.

“Richard is a very humble, unassuming scientist, and he’s not a great self-publicist. He prefers to sort of let his research do the talking. So he’s often – particularly by people who’ve entered the field in more recent years – not well recognised by many working in the field.”

Batten said Robson was pivotal in creating an entirely new area of study in chemistry.

“It was just really satisfying that the [Nobel Prize] committee had obviously done their due diligence and searched through the history of the field properly and where it really started,” he said.

During his PhD at the University of Melbourne in the late 1990s, Batten worked closely with his two supervisors, Robson and Bernard Hoskins, describing his time under their mentorship as “wonderful”.

“At the time, we thought we were doing something interesting, but if you’d have told me what the field has become, it would have blown my mind,” he said.

“Richard’s real genius is to think of things really simply but in a way that people haven’t [done] before. And then as soon as he says it out loud or demonstrates what he’s thinking, it’s immediately obvious, and you wonder why you hadn’t thought of it already.”

Batten said that at the time, their research group was essentially the only one in the world pursuing these ideas.

Loading

“One of the great pleasures of my own career is literally watching the birth and the creation of a whole new field of chemistry, essentially from a front-row seat.”

The first Nobel Prize of 2025 was announced on Monday, awarding Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell and Dr Shimon Sakaguchi the prize in medicine for their discoveries in peripheral immune tolerance. Tuesday’s physics prize went to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret and John M. Martinis for their research in subatomic quantum tunnelling that advances the power of everyday digital communications and computing.

The literature prize will be announced on Thursday night before the Nobel Peace Prize is announced on Friday.

Read the full article here