George Kourounis will never forget his first encounter with the “Door to Hell”. A fiery chasm 30 metres deep, it has burned uncontrollably for decades, fuelled by an apparently inexhaustible supply of natural gas from deep below.

The pit is the result of a mining accident in remote Turkmenistan, one of the former Soviet states in Central Asia dubbed “the Stans” along with Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Turkmenistan, more wary of visitors than the rest, is often described as a “hermit” nation, a land of high-altitude desert and mountains, rich in resources yet relatively impoverished, where internet and media have been censored by a succession of dictators whose whims – such as a decree that all cars in its capital must be white – would seem comedic were they not law.

For the few travellers who’ve made it there (Turkmenistan doesn’t get many), the Darvaza gas crater has long held a weird fascination. So Kourounis, a professional adventurer who’s swum with piranhas and great white sharks, chased twisters through Midwest America’s Tornado Alley and married his wife, Michelle, on the edge of an erupting volcano, ventured to Turkmenistan to climb to the pit’s flickering bottom to see exactly what was there, a scientific expedition backed by National Geographic.

George Kourounis with his flag from the New York-based Explorers Club before taking the plunge into a pit of burning methane in the desert in Turkmenistan.

“I’d been studying this place for months and months, looking at every single picture online, trying to learn as much as I could before actually setting foot in Turkmenistan,” he tells us from his home in Toronto, Canada. “But the moment I walked right up to the edge and felt that heat on my face and looked down inside the crater for the very first time with my own eyes, well, my first thought was … this is impossible.”

In fact, many unlikely things are possible in the Stans. It is, as any tourist brochure will tell you, a region of stunning natural beauty, vast steppes and jagged mountains; of yurts, forts and one of the world’s oldest horse breeds, the Akhal-Teke, fast and resilient and with uncannily metallic-looking coats; of cosmodromes, walnut groves and waterless seas. Its “Silk Road” heritage gets even seasoned travellers (and superpowers) misty-eyed. Yet it remains something of an enigma in the West, a “road less travelled”, although that might be starting to change.

So, what is life like in the Stans? Why will we be hearing more about them in the coming years? How are Russia and China involved? And why, like George Kourounis, would you want to visit?

A golden buckskin Akhal-Teke stallion, one of the world’s oldest horse breeds, from Turkmenistan. Credit: Getty Images

How did the Stans come into being?

The Stans, home to some 80 million people, are among the world’s newer nations. Until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, they were dominions of conquerors, khans, warlords and “hordes”, from Alexander the Great to the Mongols, Persians, Turks and Tsars. Traditionally, their people are mostly Muslim, a mix of nomadic and settled, and speak Turkic dialects (although Tajik, the tongue of Tajikistan, is closely related to Farsi in Iran and Dari in Afghanistan). Yet the people don’t think of themselves as homogenous Central Asians, says Gulshat Rozyyeva, a research scholar at ANU’s Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies, originally from Turkmenistan. “It’s more to do with your ethnicity, like: ‘I am Turkmen. You are Kazakh or Kalmyk’.”

Their borders, drawn up by Soviet bureaucrats, left some enclaves of cultural or tribal groups isolated from their clans.

Over the centuries, some invaders pillaged – in a land of little cultivation, it was convenient for the strong to simply take from the weak and move on to richer pastures – while others stayed and left more of a legacy: language, religion, culture. The lands now known as Tajikistan, for example, were ruled by the Persian Samanid dynasty in the ninth and 10th centuries, Genghis Khan in the 13th century then, a century later, the Turkic ruler Timur, or Tamerlane, whose empire brought Central Asia not only savage death and destruction but, in the years after his death, a renaissance in art, literature and architecture. Some of it remains in stunning cities, created by masons and craftsmen Timur had captured from other lands, not least Samarkand in modern-day Uzbekistan, where Timur’s tomb remains.

A public square called the Registan in Samarkand surrounded by three madrasas, including buildings from the era of Timur. Credit: Getty Images

The so-called Silk Road – actually several routes of caravan watering holes and trading posts – linked Western Europe and China. (The term “Silk Road” actually wasn’t dreamed up until 1877, by a Prussian geographer surveying China for a railway to Berlin, notes William Dalrymple in his history of India’s influence on the world, The Golden Road.) Yet it was the Russians, who formally occupied the region from the 1860s, who arguably wrought the largest changes to the Stans in more modern times. In the 1920s, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin formally divided colonial Russian Turkestan into five states: the Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tajik, Turkmen and Uzbek Soviet Socialist republics.

Their borders, drawn up by Soviet bureaucrats, left some enclaves of cultural or tribal groups isolated from their nominal homelands. Like the lines hastily sketched by British and French public servants to slice up colonial control of the Levant (which include today’s Lebanon, Syria and Jordan) after the fall of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, this was a rush job with consequences: border disputes are still ongoing.

“They were going to create a utopia,” writes the Norwegian travel writer Erika Fatland in Sovietistan, her 2015 account of adventures in the region. “In the space of a few years, the people of Central Asia underwent a managed transition from a traditional, clan-based society to hardcore socialism. Everything from the alphabet to the position of women in society had to change, by force if necessary. While these drastic changes took place, Central Asia in effect disappeared from the world map.”

Abandoned boats on dried-up the Aral Sea in Uzbekistan.Credit: Getty Images

It was under this veil that, from the 1960s onwards, the Aral Sea, stretching across Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, was drained almost dry to feed crops by Soviet agriculturalists, particularly water-intensive cotton, leaving it a network of salty puddles contaminated with the insecticide DDT and pocked with stranded rusting ships. Regarded as one of the worst environmental disasters in recent times, the eerie Aral now generates just a little income from stickybeaking tourists.

The Soviet legacy includes a trove of striking Brutalist architecture with Persian and Islamic twists … and sumptuously decorated metro stations in Tashkent.

Also in Kazakhstan are former Soviet nuclear test sites that continue to leak radiation. Turkmenistan’s gas crater is believed to have been caused by another Soviet-era initiative around 1965: the land collapsed during drilling for gas, forming a pit about 75 metres wide, whence methane seeped up, creating a hazard to nearby settlements. To burn off the excess, geologists set it alight – whoosh! – except it never went out (although it has finally begun to dim just recently).

The Soviet legacy also includes: a trove of striking Brutalist architecture with Persian and Islamic twists (including elaborate mosaic tiles); the world’s largest space launch site, on the Kazakh steppe at Baikonur, from which the likes of Yuri Gagarin and poor Laika the dog careered into their respective orbits; sumptuously decorated metro stations in Tashkent, one of which, Kosmonavtlar, has a ceiling of glass stars paying tribute to the cosmonauts; and, not far out of the city, a “solar furnace” installed in 1981 with a 54-metre-high parabolic wall of mirrors that can focus the sun’s rays into a 3000C point (and which is open to tourists)

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the five republics updated their names, ditching the Soviet-era appendages for the Persian-language suffix “stan”, meaning “land of” – as in, the land of the Uzbeks or the Turkmen or the Kazakhs, much like Scot “land”, Fin “land” and Eng “land”. Pakistan and Afghanistan are sometimes included as fellow “Stans” but differ from the central Asian five as neither was once a Soviet state. There are other Stans, too, that are regions or districts including the autonomous zone Karakalpakstan in Uzbekistan, Khuzestan, a province of south-western Iran, and India’s Rajasthan. Pakistan, meanwhile, is not actually a “land of” anything but an acronym, apparently coined by a public servant at the birth of the nation in 1947, to represent the regions of Punjab, Afghanistan (the Pathan-inhabited Northwest Frontier Province), Kashmir, Iran, Sind, somewhere known as “Tukharistan”, Afghanistan and Baluchistan.

The first woman in space, Valentina Teroshkova, is one of the cosmonauts featured at Kosmonavatlr metro station in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Credit: Getty Images

“Turkmenistan always fascinated us,” says Matt Laughton, who visited in 2024 with his partner Julia, with whom he runs popular travel vlog Matt and Julia. The couple also visited the Door to Hell, where they stayed in a traditional yurt. “Officially, it isn’t allowed to travel to Turkmenistan independently,” he tells us. “However, we managed to travel, let’s say, ‘semi-independently’. We found a tour company that allowed us a lot of autonomy; we managed to explore Ashgabat, the capital, going to the more ‘lived-in’ part of the city, stopping at cafes, markets and ‘chaikhanas’, or teahouses. We also took the train on our own, mixing with locals, and hearing from them what life is really like in Turkmenistan … when the government isn’t watching.”

Nearby Kyrgyzstan is largely mountainous, home to Pobeda Peak, at 7049 metres the highest in the region and known as particularly challenging for mountaineers. Of the five Stans, Kyrgyzstan (also known as the Kyrgz Republic) is nominally the most democratic, having twice overthrown autocratic leaders, most famously in its 2005 Tulip Revolution, although its parliament remains corrupt and risks sliding back, according to the think tank Freedom House, whose annual report paints a gloomy picture for civil liberties in the region.

Elections in Kazakhstan are “neither free nor fair”, it says. Uzbekistan “remains an authoritarian state with few signs of democratisation”. Tajikistan’s President, Emomali Rahmon, “severely restricts political rights and civil liberties”. Turkmenistan, where former president Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow (an ex-dentist and father of the current president) once ordered that all cars in Ashgabat be painted white to match his beloved marble-clad buildings, “is a repressive authoritarian state”. (Ashgabat was declared to have the “highest density of white marble-clad buildings in the world” by the Guinness records organisation in 2013.)

Ashgabat, Turkmenistan’s capital, a city of white marble buildings and where all cars must be white. Credit: Alamy

Indeed, says Laughton, “the lowlight [of the trip] was the constant fear of being watched. Although we could explore each place we were in independently, we were still on a strict schedule to move on from place to place. We noticed on the last couple of days our driver kept receiving phone calls roughly every 30 minutes, asking where we were. He later explained this was the ‘ministry of tourism’ checking up on us constantly.”

Kirill Nourzhanov, from the Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies at ANU, offers this context: “The [position of] president and strong authoritarian rule is widely seen by the majority of the population everywhere across Central Asia as the custodian of stability. Stability is much more important than political freedom.” Tajikistan, for example, endured five years of brutal civil war in the ’90s, costing some 100,000 lives and displacing many hundreds of thousands. Current President Emomali Rahmon was seen to have played a pivotal part in bringing peace to the fledgling nation.

Moreover, says Luca Anceschi, a specialist in Central Asian Studies at the University of Glasgow, none of the Stans has experienced much in the way of liberalisation, ever. “Once you recognise that this is an extremely authoritarian region, that the politics of the region have been governed that way for 30 years, and actually even before – because the Soviet Union was an authoritarian experience – you then start to make sense of things.”

In practice, even the most overbearing dictators can only reach so far. Says Laughton: “One curious thing we discovered in Ashgabat was that every cafe we visited had their Instagram name on display for people to follow. For a country with a supposedly closed internet system this was baffling. We later found out from a local that nearly everyone uses VPNs [virtual private networks] and, in reality, everyone uses the same apps and social media as the outside world.“

Turkmenistan has a national holiday for its native dog breed the Alabai, one of which (a border guard dog) is seen here being petted by his handler in national costume.Credit: AP

Does Russia or China have more influence in the Stans?

Although the five Stans span a vast 4 million square kilometres in total, they are positioned between their old conqueror Russia to the north, China in the far east, the theocracy of Iran and extreme Islamism in Afghanistan in the south, and, to the west, the Caspian Sea, Turkey and Europe beyond.

‘They’re doing good business, locked into all sorts of unions, blocs, alliances, so there’s no prima facie rationale for Putin to do the nasty by them.’

Kirill Nourzhanov, Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies at ANU

So they were understandably alarmed when Russia invaded another neighbour, Ukraine, in 2022 (as were the former Soviet republics of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia). “In Kazakhstan, in particular, there is a considerable concern about Russia’s aggressiveness,” says Nourzhanov, “especially given that there are plenty of Russians living in the northern and north-eastern parts.”

On the other hand, he says: “The political elite in Kazakhstan is reasonably assured that [a Russian invasion] would be a very unlikely turn of events because Kazakhstan does not have a beef with Russia. They’re doing good business, locked into all sorts of unions, blocs, alliances, so there’s no prima facie rationale for Putin to do the nasty by them.”

Russian is commonly spoken in Kazakhstan, where it is seen as a mark of prestige and urbanity, says Nourzhanov. There is also a widespread perception, he says, “that Russia offers greater mobility, great opportunities to people in Central Asia, to the young ones, than the West”.

In Kyrgyzstan, home to Kumtor, the largest open-pit gold mine in Central Asia, and with pockets of rapid modernisation, many workers still travel to Russia for largely menial jobs and send remittances home. Since the war in Ukraine, this has brought additional perils, with some workers from Central Asia coerced into joining Russian forces in a so-called shadow army, according to the Atlantic Council. “These are not professional soldiers. They are more likely former cleaners, street sweepers, construction workers – undocumented migrants, often trapped in legal limbo, lured with false promises of fast-track Russian citizenship or pulled straight from prisons and detention centres.”

Yet older Central Asians might feel nostalgia for Soviet rule, suggests Dilnoza Ubaydullaeva, a research fellow at ANU’s National Security College.

For now, none of the Stans appears to have openly endorsed or condemned Russia’s aggression; when the Kyrgyz city of Osh pulled down a giant statue of Lenin in June, authorities claimed it was just to move him to another spot. “They are also extremely concerned about pressure from the West,” says Nourzhanov. “Everyone coming from Washington or Brussels tries to twist their arm to join the sanctions regime, to join the high moral course of opprobrium against Russian aggression. Why would they do that? It’s against their national interests, and that’s why they basically stick to a neutral position.”

‘Two generations after the collapse of the Soviet Union and independence, all five Stans have become very self-assured, confident nation states.’

Kirill Nourzhanov, Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies at ANU

Russian trade with the Stans, meanwhile, is booming, writes Annette Bohr of the London-based policy institute Chatham House. “Moscow has been making particularly significant inroads into the energy sectors of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan as it attempts to find new markets for its exports as a consequence of sanctions,” she writes.

Turkey, too, remains a key economic partner and is a strong draw for the Stans’ young, enticed by job opportunities and Western modernity. The Turks, as a people, once inhabited central-east Asia then pushed west from the 11th century across Central Asia into Anatolia, now modern-day Turkey, hence the prevalence of Turkic language and culture in four out of five of the Stans (Tajik, spoken in Tajikistan, is a Persian language, not Turkic).

In 2009, Turkic-speaking Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan joined with Azerbaijan and Turkey to form the Organisation of Turkic states. “The economy is undoubtedly an important aspect of the OTS members’ cooperation but it is not the only one,” reports The Times of Central Asia. “Culture, including language as its essential part, and history also play crucial roles in the Turkey-dominated group’s ambitions to create a unified Turkic world.”

The Institute of Solar Physics, built in the ’80s near Tashkent in Uzbekistan, features a glittering solar furnace.Credit: Getty Images

Then there’s China, which announced its global Belt and Road Initiative in 2013 in Kazakhstan’s capital, Astana. The scheme, which now counts more than 150 countries as members – including all five Stans – promises investment loans, joint ventures and infrastructure projects. Ostensibly, it represents China’s modern version of the Silk Road but it’s also clearly another arm of Chinese influence.

“While nobody knows what the Belt and Road Initiative is all about,” says Nourzhanov, “there’s some very real money pouring into Central Asia and manifesting itself in the form of glistening railway lines and shiny pipelines and power-generating facilities. So the Chinese presence is growing and growing and growing. It’s making a real impact on daily life and economic performance in Central Asia.”

Another lingering influence is radical Islam, perpetuated by groups such as Islamic State Khorasan Province, a branch of IS. After independence, some young people from Central Asia were drawn to Turkey, where some encountered radical Islamist movements for the first time, says Ubaydullaeva, religion having been effectively banned by the Soviets. The Stan governments are largely secular and wary of threats to their regimes. Even beards and hijab can be deemed problematic; the Taliban, of course, are just across the border in Afghanistan.

Yet what is often lost on outside observers, says Nourzhanov, “is that two generations after the collapse of the Soviet Union and independence, all five Stans have become very self-assured, confident nation states. They’re simply not reducible to being, you know, pawns in the new Great Game [the 19th-century rivalry between the British and Russian empires] or living in someone’s backyard.”

Actor Sacha Baron Cohen in a scene from Borat Subsequent Moviefilm, the sequel to his film satire that was banned in an unamused Khazakhstan. Credit: AP

What’s next for the Stans?

Kazakhstan was less than pleased to feature as the home nation of the bumbling title character of Sacha Baron Cohen’s 2006 satire Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan. It banned the movie and threatened to sue Baron Cohen but ultimately figured any publicity was good publicity and by 2012 had even adopted Borat’s catchphrase for a tourism campaign: “Kazakhstan – very nice.”

‘Go beyond the eccentricities … Try to understand that it all happens for a reason.’

Luca Anceschi, Central Asian Studies specialist, University of Glasgow

Of course, resources-rich Kazakhstan is nothing like it was portrayed in the movie (some of which was shot in Romania, in any case). Ultra-modern Astana (literally, “capital” in Kazakh) is a tableau of glitzy monoliths, described by one local to us as “a lot like Dubai, but on ice” (summers there can hit 35C, winters can be minus 35). The former capital, Almaty, is a thriving cultural hub near ski fields that enjoys a milder climate – a great place to live, according to Alex Walker, an Australian CEO of a junior mining company that’s exploring in Kazakhstan for copper and gold. “Fantastic nightlife, great people, great culture and safe,” he says. With one caveat: “You need to be super into your meat, your potatoes – you need to be absolutely into it. Not highly recommended for vegans.”

A food market in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, where meat dishes are a feature of the cuisine. Credit: Alamy

Paul Cohn laughs at Western misconceptions of life in Kazakhstan, where he has lived for close to 20 years and is now both a partner with the consultancy Ernst and Young and Australia’s honorary consul. “I think people, in their minds, have some kind of idea, possibly because of the ‘Stan’ at the end of the name, that it’s a lot more dangerous or backward or, you know, dusty or desert-y or whatever.” In reality: “A lot of households have three cars in the garage. The quality of life here, I would say, is not dissimilar to a lot of southern European countries.”

To better understand the region, says Anceschi, “go beyond the eccentricities, beyond the idiosyncrasies of the region. Try to understand that it all happens for a reason.”

Women in Turkmenistan’s white marble capital, Ashgabat.Credit: Alamy

Relations among the Stans themselves range from warm to frosty. In 1994, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan formed an economic union, joined in 1998 by Tajikistan, to allow free passage of labour between the nations. There is a growing regionalism in Central Asia, says Nourzhanov, even if for decades “they simply could not get the collective act together”. “There’s still a fair deficit in terms of trusting each other.”

‘Before long, maybe in the next 10 years, Central Asia will simply become a distinct regional bloc.’

Kirill Nourzhanov, Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies at ANU

Even cautious Turkmenistan just this year took its first tentative steps towards joining a wider group, entering a free-trade agreement with Uzbekistan to remove customs duties on most goods produced in both countries. The five Stans have also begun to develop common stances in areas such as foreign policy and the passage of oil and gas pipelines. “This is a sign of growing maturity,” says Nourzhanov. “Before long, maybe in the next 10 years, Central Asia could well become a distinct regional bloc.”

At the first summit between the Stans and the EU, in April 2025, leaders are from left: Tajikistan’s Emomali Rahmon, Kazakhstan’s Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, European Council President Antonio Costa, Uzbekistan’s Shavkat Mirziyoyev, EC President Ursula von der Leyen, Turkmenistan’s Serdar Berdimuhamedow and Kyrgyzstan’s Sadyr Japarov.Credit: AP

Earlier this year Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan signed an historic accord recognising their respective borders, ahead of another historic meeting in Samarkand of five Central Asian heads of state and the two presidents of the European Union. “It seems the EU is now racing to catch up after years of under-engagement, recognising Central Asia’s strategic role in emerging global supply chains and connectivity,” Oybek Shaykhov, secretary-general of the Europe-Uzbekistan Association for Economic Cooperation, told The Diplomat. The EU is increasingly interested in the Stans’ natural resources; in 2024, it bought more than 70 per cent of Kazakhstan’s oil exports, according to the Lowy Institute.

For tourists, while visa red tape is easing, travel in the region can be hairy: the Australian government recommends taking a high degree of caution in Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, due to the threat of crime, terrorism and civil unrest – with a warning to not travel at all to the regions bordering Afghanistan. Kazakhstan, the wealthiest and most “Western” of the five, was recently given the green light by Smart Traveller. Some 15.3 million tourists visited it in 2024, according to its Tourism Industry Committee. Its old capital Almaty was lauded in The New York Times’ 2024 list of 52 Places to Go This Year for its “neo-nomad” cuisine, great coffee and other “endless delights” such as “a mustachioed man playing the accordion in front of the kaleidoscopic Ascension Cathedral”.

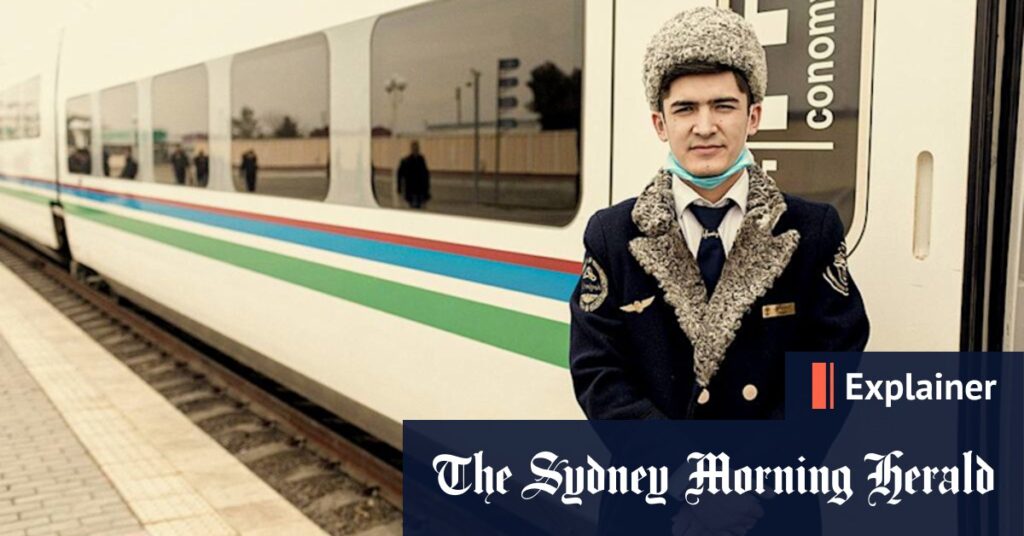

A train conductor in Samarkand. A network of fast trains links major cities in Uzbekistan. Credit: Alamy

As for Uzbekistan, government efforts to lift its tourist numbers are working, with 6.6 million in 2023, up from 2.7 million in 2017. More than a million visited in April alone, according to the Global Tourism Forum, whizzing from one world-heritage city to the next on bullet trains. Its ancient city Bukhara features in this year’s New York Times places to travel list, and, for different reasons, in the news: a sprawling tourist development in a “buffer zone” next to the old part of the city has seen UNESCO urge the government to hit pause. One local cultural heritage group opined that “a fake ‘Orient’ in visual proximity to the historical core of Bukhara is doomed to … repel citizens and scare away tourists”. An architect from Bukhara told the BBC his city “risks becoming a Venice in the desert”.

A scenic route in Tajikistan.Credit: Alamy

Some travellers are venturing to more far-flung areas of the Stans, says Joan Torres of niche travel business Against the Compass. The drive from Kyrgyzstan to Tajikistan along a highway that reaches 4000 metres is particularly spectacular, she says. “It’s all isolated settlements and gorgeous landscapes. Sometimes you drive for miles and you don’t see another car.” But for very remote areas – “100 per cent not set up for tourism” – it’s best to at least hire a guide with a four-wheel drive. Of the 1.2 million foreigners who visited Tajikistan in the first nine months of 2024, just 1900 were from Australia.

George Kourounis walks through the methane hole in a heat-resistant suit.

Kourounis’ trip, back in 2013, took two years of planning: visas for Turkmenistan must be applied for months in advance and require a separate “letter of introduction”, usually issued by a tour company. Visitors who make it inside typically submit their itinerary to state-authorised guides.

Loading

To Kourounis’ surprise, though, the government not only co-operated but sent two geologists to assist him in “unlocking the secrets” of the burning pit. “They were of tremendous help, providing us with a lot of historical information about how old the crater was and how it formed,” he says. In the end, he put on a custom-built heat-resistant suit and rappelled over the precipice. The project was – obviously – scary, he tells us, but ultimately rewarding. “There were many surprises along the way, which makes sense when you’re trying to do something that no one’s ever done before.”

This Explainer was brought to you by The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald Explainer team: editor Felicity Lewis and reporters Jackson Graham and Angus Holland. For fascinating insights into the world’s most perplexing topics, sign up for our weekly Explainer newsletter. And read more of our Explainers here.

Felicity Lewis, Jackson Graham and Angus Holland.Credit: Simon Schluter

Read the full article here