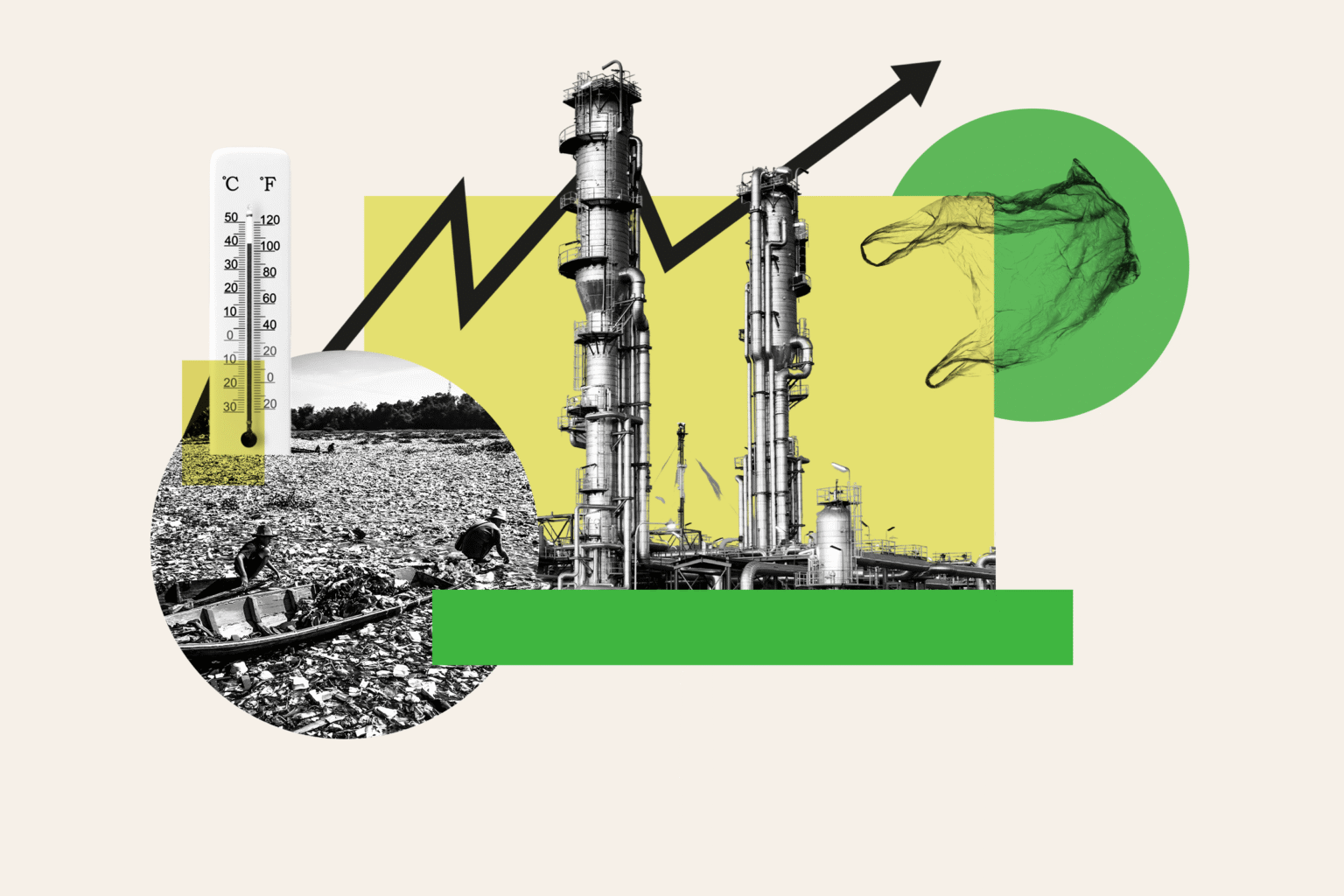

It was the images of plastic waste clogging rivers, covering shorelines and killing marine wildlife that helped to galvanize world leaders three years ago to start work on a global treaty to reduce the glut of plastics.

But there is also a less visible form of pollution from plastics taking a toll on our atmosphere—the massive amount of greenhouse gases generated by plastic production. That’s why the work underway this week in Geneva, Switzerland, to finalize a plastics treaty is a significant opportunity to address climate change.

Plastics and the petroleum used to produce them are responsible for roughly 5 percent of the world’s industrial greenhouse gas emissions—more than the emissions from the aviation sector. Without intervention, climate scientists warn, the growth of plastics will drive those emissions higher, making it far more difficult to meet international targets to prevent the worst warming.

“Decarbonizing the plastics sector is essential for staying within safe climate limits,” Pablo Blasco Ladrero, a researcher at the non-profit organization NewClimate Institute, told Newsweek via email. Ladrero is a co-author of a new report on plastic’s climate impacts.

If the world’s production of plastics continues on its current trajectory, Ladrero said, it would account for a much larger portion of the carbon we could emit while staying on course to meet the most ambitious targets under the Paris Climate Agreement.

“By mid-century, plastics alone could consume 26 percent to 31 percent of the remaining carbon budget,” he said.

A global plastics treaty holds the promise of an elegant solution that addresses multiple environmental challenges at once. Limiting plastic production could help reduce the emissions warming our planet, the trash fouling our oceans and even the microplastics coursing through our bodies.

But doing so will involve overcoming opposition from some of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful political interests.

A Role for Recycling

The last round of talks on the global plastics treaty ended in stalemate when a handful of petroleum-producing countries objected to a cap on plastic production.

While many observers of the treaty process told Newsweek they still hope for a strong outcome from the talks now underway, many of them voiced skepticism about chances for any meaningful limit on plastics.

“I’m 60 percent [sure] that we will have a treaty,” Steve Alexander, president and CEO of the Association of Plastic Recyclers, said during a Newsweek panel discussion last month. “I’m much less optimistic we’ll have a treaty with any lasting teeth to it,” he said.

Another member of the panel, Professor Douglas McCauley, directs the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory at the University of California, Santa Barbara. McCauley and his colleagues have modeled the potential effects of policies to rein in plastic waste and what the future will look like if we stay on the business-as-usual trajectory.

“Emissions increase immensely with business as usual, because we continue to extract oil and gas,” McCauley said. “It’s a 37 percent increase in emissions over where we’re at right now.”

In work published in the journal Science in December, McCauley and his co-authors found that without global policy intervention, greenhouse gas emissions related to plastics would rise to 3.35 gigatons by 2050. That’s about the same as the emissions from 9,000 natural gas-fired power plants operating for a year.

Capping global virgin plastic production at 2020 levels would be the best way to drive down both plastic waste and greenhouse gases from plastic, he said.

But a cap on plastic production is not the only option in play at the talks in Geneva, and McCauley’s team found other policies could also reduce emissions. A global mandate for plastic products to include a minimum of 40 percent recycled content could also take a big bite out of greenhouse gases.

“When you use recycled material, you reduce energy utilization versus using virgin material by almost 80 percent,” Alexander said. “You reduce your greenhouse gas emissions by a similar amount.”

Counting on Consumer Sentiment

Current global recycling rates for plastic hover at just under 10 percent. And while recycling can cut waste and emissions, it won’t eliminate them.

“Recycling will not solve the crisis we’re in when it comes to plastic,” CEO of Elopak Thomas Körmendi told Newsweek. “We need to find alternatives.”

Oslo-based Elopak is in the alternative packaging business, providing fiber-based cartons to major food and household product companies in more than 40 countries.

Elopak will be a participant in Newsweek‘s upcoming “Pillars of the Green Transition” event on September 24th during Climate Week NYC.

Elopak commissioned a life cycle assessment study of the carbon emissions associated with different types of beverage containers, including the production and disposal of the packaging and energy required for shipping.

Fiber cartons were found to produce about a third less CO2 than HDPE plastic bottles and about 60 percent less than bottles made from PET plastic.

Körmendi said client companies that have set ambitious climate goals find that attractive, and in some markets, such as the European Union, new regulations on plastic packaging make alternatives such as cartons more appealing.

A strong global treaty on plastics could help to level the playing field elsewhere by holding plastic packaging producers and users accountable for the environmental costs that are now foisted onto the public.

But Körmendi said he is not optimistic about the product that will emerge from the Geneva talks. Instead, he said, he puts more faith in the rapidly changing consumer attitudes about plastic.

“There is a very strong consumer sentiment everywhere, including in the U.S. by the way, that we want to reduce our plastic consumption,” he said.

The visceral public reaction to the visible plastic waste is what will ultimately drive down both plastic garbage and greenhouse gases.

“It is just something that is very visual and, I think, emotionally disturbing,” Körmendi said. “I find probably that is a stronger motivation than waiting for global treaties to be signed.”

Plastics, Pollution and Petroleum Politics

The connection between plastics and petroleum has also created a powerful political bloc that has stymied efforts for a strong treaty. Late last year at talks in Busan, South Korea, oil-producing nations led by Russia and Saudi Arabia objected to language that would cap the overall production of new plastic and thus limit an important growth market for oil and gas.

As deployment of renewable electricity sources grows and electric vehicles (EVs) gain traction in the global market, the International Energy Agency forecasts that oil demand will level off, raising the importance of petrochemicals.

“Plastics have become a crucial growth market for fossil fuels, especially as demand in traditional sectors like road transport and power generation is projected to decline in the coming decades,” Ladrero of the NewClimate Institute said.

“Efforts to decarbonize plastics directly challenge fossil fuel interests, contributing to the stalemate in negotiations.”

On Thursday, the nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law released an analysis of participants in the Geneva talks that identified 234 fossil fuel and chemical industry lobbyists registered to attend, the highest at any negotiation for the plastics treaty. Industry lobbyists outnumber the combined diplomatic delegations of all 27 European Union nations.

“The treaty meant to stop plastic pollution is being shaped by those who profit from it,” Dylan Kava, strategic engagement and communications lead for the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network, said at a press event in Geneva.

As the talks approached the halfway point on Friday, civil society groups issued a statement that the process was “not on track” to deliver an acceptable result.

“The same, tired tactics are still causing gridlock at the negotiating table,” Erin Simon, vice president of plastic waste and business for the World Wildlife Fund, said in an email from Geneva. “If we can’t turn this around, we risk leaving Geneva either empty-handed or with an empty treaty.”

Read the full article here