For many years inflation seemed like the White Walker of economic worries. Elder economists muttered darkly of ancient times when the CPI rose by double digits, yet many a year had passed with no inflation sightings. Then 2021 happened. Suddenly, a new generation of economists witnessed firsthand just how central price stability is to American politics.

Carola Binder was one of those young economists watching carefully. She was particularly struck by a Washington Post article in 2022 that asked experts what they thought the White House should do about rising prices. This seemed odd to her because dealing with inflation was supposed to the Fed’s responsibility. Yet the more she thought about it, the more she realized politics and prices have always been tied together.

Her new book: Shock Values: Prices and Inflation in American Democracy traces the history of this relationship. Like all relationships, it’s complicated.

Liberator or Oppressor?

Stability of prices, particularly those for agricultural products, was a continual and contentious issue in American politics right from the beginning. What was not constant, however, were views on how to achieve it. For instance, gold’s reputation and its political constituency rotated through time.

Andrew Jackson, a firebrand advocate for farmers and western settlers, saw adherence to a gold standard as a way to avoid excessive government power. As President in 1832 he vetoed the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States, thinking that a system based on paper money favored the wealthy relative to ‘real people’.

But later that century Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan, also an advocate for rural folks and farmers, took the opposite view. He saw gold as a tool that favored the elite over the common man, famously concluding his presidential nominating speech with “you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

Modern gold advocates seem like a blend of both. They are often government distrusters like Jackson, but also wealthy and powerful, as Bryan feared.

There has also been cyclicality in views about whether control of paper money promotes or degrades democracy. Abraham Lincoln saw it as a tool for more equitable distribution of power:

“The people can and will be furnished with a currency as safe as their own government. Money will cease to be the master and become the servant of humanity. Democracy will rise superior to the money power.”

The highwater mark of political control over inflation was probably during WWII when the Office of Price Administration was put in charge of setting and enforcing price controls to keep a lid on wartime inflation. It enlisted more than 100,000 volunteers to monitor and report local stores for violations. This was praised by its supporters as “big democracy in action” – although it feels more like “Big Brother” in action.

Over the intervening decades the pendulum swung in the opposite direction. Once a determined Paul Volcker stamped out inflation in the 1970’s, a consensus emerged that to get stable inflation we needed less democracy. Specifically, we needed an independent central bank that operated at arms length from elected representatives.

Lincoln might be shocked that politicians willingly ceded this power, but it maps to their incentives. They can criticize the Fed when things go wrong, but don’t need to take any action themselves. Price stability did seem to coincide with the delegation of authority to central banks and we entered the white walker era where inflation disappeared from political debate.

All that changed in 2021.

Inflation Still Matters

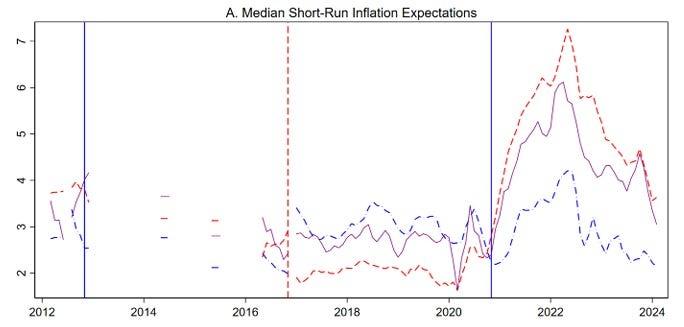

The current election proved that inflation still matters. The graph below is taken from one of Binder’s recent research papers and shows inflation expectation by political party with Republican expectations in red and Democrats in blue.

During Trump’s first term Republicans had lower inflation expectations than Democrats. That reversed almost immediately when Biden took over. Although everyone’s expectations rose during Covid, by the beginning of 2024 Democrat expectations were actually below pre-pandemic levels while Republican expectations hovered around 4%.

Undoubtedly some of this is due to the survey being used to express an opinion on the ruling party. This shows up clearly in the next graph, where I plot overall sentiment by party affiliation.

Central banks are focused on ensuring that inflation expectations do not become ‘unanchored’. The graphs strongly suggest that this is not purely an economic outcome. Inflation expectations can’t be separated from political views. This is true now and, as Binder’s book shows, it’s been true for over two centuries.

I ended our Ideas Lab podcast by asking Binder about this quote from the famous economist Irving Fisher:

In nearly every country there exists a party, consisting of debtors and debtor-like classes, which favors depreciation. A movement is therefore at any time possible, tending to pervert any scheme for maintaining stability into a scheme for simple inflation.

The quote itself – that debtors prefer inflation – isn’t novel. However, our current moment is interesting in that the biggest debtor – the government – is also in control of money. I asked Binder if that means the impulse toward inflation is particularly dangerous now?

She said her work suggests that we’re still a long way from inflation expectations becoming unanchored and that having an independent Fed will protect us against government pressure toward inflation. That’s a reasonable answer, and basically the one I would have given a few years ago. But I’m no longer sure central bank independence is in our long-term best interest.

More on this in the coming months!

Read the full article here