Combining that antibody with an existing toxin inhibitor called varespladib (which is already used in Australia) expanded protection to taipans and tiger snakes.

Adding a second antibody isolated from Friede’s blood called SNX-B03 offered complete protection against four snakes including the mulga, or king brown – a two-metre Australian native known to “hang on and chew” victims as it injects venom – but only partial protection for death adders, which are also native.

Glanville and his co-authors write in the resulting paper published in Cell on Saturday that their results show proof of principle for building a universal antivenom.

Baby tiger snakes bred recently at the Australian Reptile Park’s new Weigel Venom Centre for the production of anitvenom.Credit: Australian Reprile Park

“Australia has many venomous species of snake, but they are all of the neurotoxic ‘elapid’ type,” Glanville said. “Our Cell study presents a broad solution to elapids. Therefore our cocktail is potentially relevant to all Australian snakes.”

University of Queensland venom expert Professor Bryan Fry, however, believes the treatment would have “patchy” coverage against Australian snake bites given the ad-hoc way Friede injected himself over the years, mostly with the venom of US and exotic species.

“There would be very, very limited cross-reactivity to anything Australian, which is reflective of the fact that he injected himself with snakes that are common on the US pet trades, such as mambas and cobras,” Fry said.

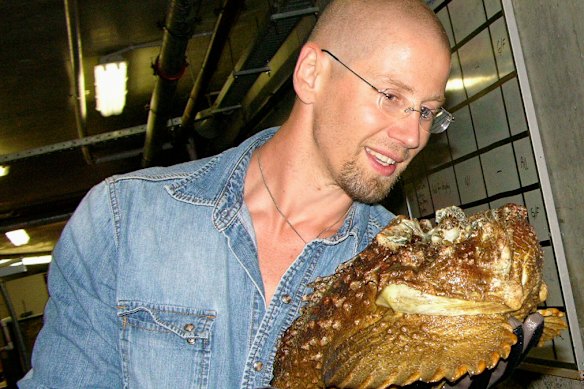

Venom expert professor Bryan Fry with a stonefish.Credit: University of Queensland

“If they’re having poor cross-reactivity with death adders, I wouldn’t expect better cross-reactivity with even more divergent kinds of snakes. There’s definitely going to be limits.”

Fry also said there was a “zero chance” a university ethics unit would’ve approved the injection of snake venom into a human under scientific circumstances.

Friede injected the venom of his own volition and had given up the practice in 2018, before the researchers began studying his blood.

Glanville said an Australian vet approached him after he presented Centivax’s early findings from the study on Friede at a venom conference, and said she was interested in trialling the treatment at her network of clinics.

The trial hasn’t been confirmed, but the researchers want to test the experimental antivenom in bitten dogs because they’re more similar in body weight and heartbeat to humans in comparison to lab mice.

Current antivenoms are generally specific to one, or just a handful, of species. Melbourne’s Commonwealth Serum Laboratories make them using venom milked and dehydrated by staff at the Australian Reptile Park near Gosford, north of Sydney.

To make antivenom, small amounts of venom are injected into an animal such as a horse over several months. Antibodies build up in the horse’s bloodstream and are extracted to make vials of treatment serum.

Loading

Treatments that work across multiple species are desperately needed given victims often can’t identify what kind of snake they copped a bite from. But is a universal antivenom ever likely to fully replace species-specific serum?

“Realistically? No, because venoms are so extraordinarily complex and so tremendously divergent,” Fry said.

Existing antivenoms remain the cheapest and safest way to treat bites for developing regions in sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia, where the most people die from snake bites, he added.

Snake bites kill up to 137,000 people per year and permanently disable 300,000 people, often through amputation.

The Examine newsletter explains and analyses science with a rigorous focus on the evidence. Sign up to get it each week.

Read the full article here